Slice of Life

10,000 BCE is generally accepted as the start of the period that would become known as the Agricultural and Neolithic Revolutions (Coyle, 2018). We had already started to eat grains, collecting the seed by hand plucking, but now, with more purposeful cultivation and harvesting with our hands and a sickle-like stone, a new era of human existence had begun (Scheuerman, 2017). Trust me when I say there is so much to explain about the origin of agriculture that archaeology classes typically spend two days to a week discussing it in different locations. I'm not going to spend much time as a talking head. Instead, what I would most like everyone to keep in mind is when the tool first appeared in life, whether it even appears in the mythology, and how it appears in art.

Artefacts with curved blades were used to harvest stalky plants. The earliest one-handed ones have been found at some of the earliest ancient sites around the world, including in Africa, the Fertile Crescent, India, and China. The everyday staple foods across these ancient areas include grains and cereals such as wheat, barley, millet, and rice. Earlier examples may have existed in mid- and southern Africa, since grains were a staple crop there too; however, archaeologists haven't yet found the tools in excavations (Coyle, 2018 & Scheuerman, 2017). This is mainly due to the lack of preservation in organic substances that are that old.

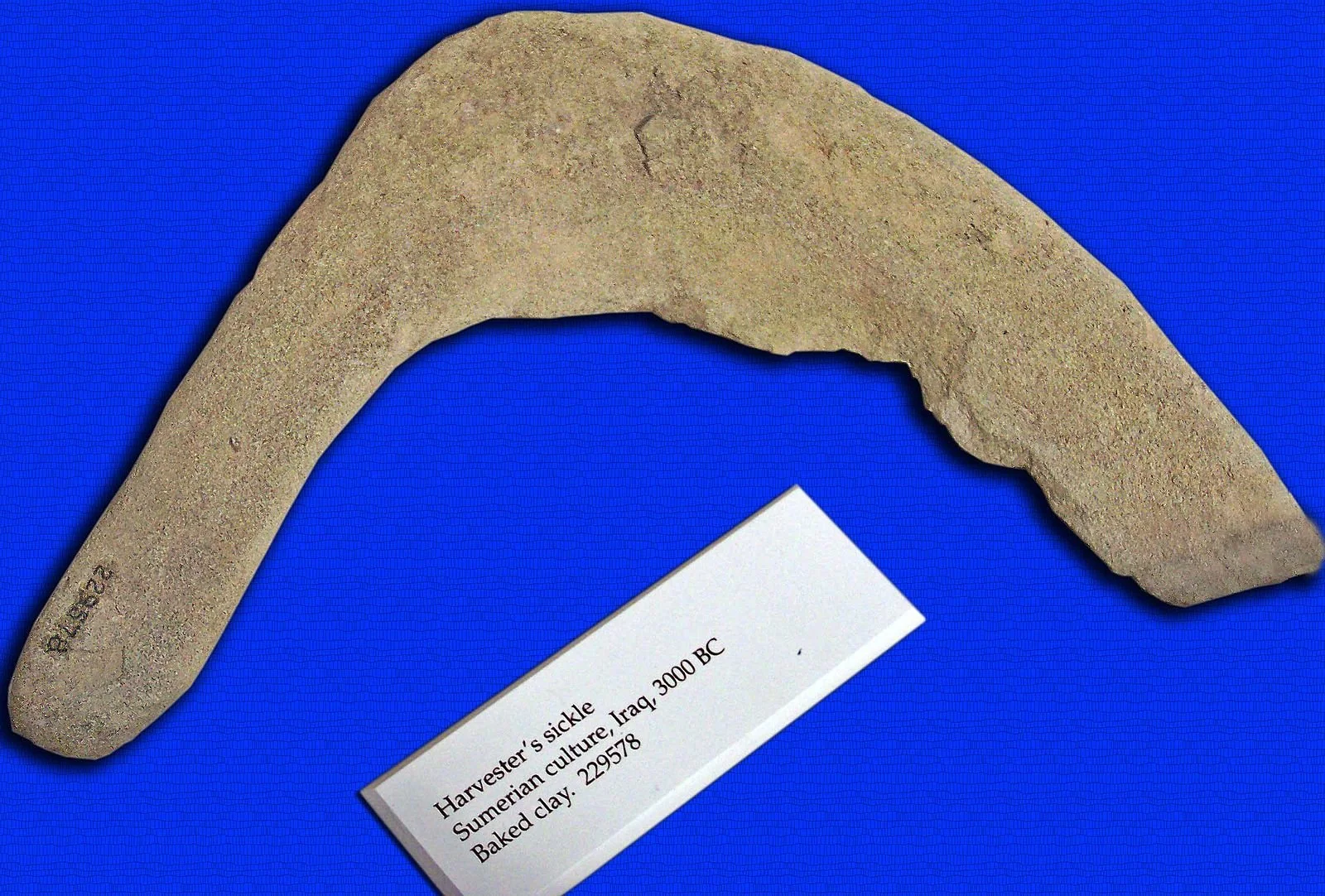

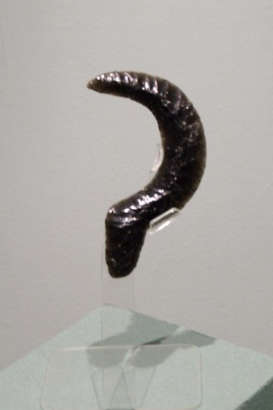

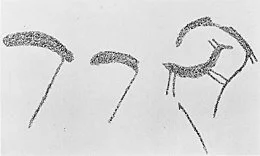

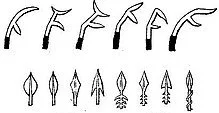

In the Bronze and Iron Ages, sickles were, as the names of the periods suggest, made out of metals. Before smelting, however, it was commonplace for sickles to be made from flint, bone, clay or wood with wooden or bone handles, and sometimes had serrated teeth of bone, flint, and obsidian. Many of the earliest sickles found look to be the serrated versions as it made for easier cutting since the base was wood, clay, or bone (shown below in figures below); these examples have been found in the regions of Mesopotamia, the Levant, Africa, the Americas, and in Asia (Banning, 1998; Unger-Hamilton, 1985 & 1989; Sommerfeld, 1994; Works, 1987, Clarkson & Shipton, 2015). Then, as technology advanced, the clean, sharp-edged variations would be made of stone and then of metals (bronze, iron, and eventually steel).

Figure 2. C. 7000 BCE, flint and resin, Tahunian culture, Nahal Hemar cave, from the Israel Museum.

Figure 3. Museum Quintana. Neolithic sickle.

Figure 4. Wooden sickle with blade composed of flints(some now lost) with a hieroglyphic inscription. 18th Dynasty, Thebes, wood and flint (Kees, A.Z. 85 (1960) pp. 445ff; Dewachter. Rd'E 35 (1984). pp. 91ff; BMS Bulletin, Summer 1988, No. 58.)

Figure 5. Several kinds of sickles were used in the class experiment based on the evolution of sickle forms in the Natufian and Neolithic of SW Asia (Clarkson & Shipton, 2015).

Figure 6. Sumerian clay harvesting sickle, c. 3000 BCE

Figure 7. Serrated wood and flint-chert sickle, Saqqara Necropolis, Carved & Rough-Hewn Style from the Early Dynastic Period -3000 BCE.

Figure 8. Obsidian sickle from Zona Arqueologica de Teotihuacan, Teotihuacan de Arista, Mexico, probably for harvesting maize. (photo by Travis S., 2008)

Figure 9. Ancient Greek iron sickle, Kerameikos Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Figure 10. A common sickle

“Rav Menashe said: And the people called the fifteenth of Av: The day of the breaking of the sickle, as they did not need the lumbering tools until the following year. (Bava Basra 121a-b)” Bystander Effect: Tu B’Av and Kitty Genovese

Figure 11. Modern harvesting sickle.

The two-handed scythe came later, the large tool/weapon we often associate with Death. This tool made harvesting faster, just like the sickle had done initially. There is evidence that the scythe existed as early as 5000 BCE, based on finds from the Cucuteni–Trypillia settlements in Central Europe. According to the Flesh of the Gods, the ancient Scythians grew hemp and harvested it with a hand reaper/scythe (Emboden, 1974). They weren't seen to actually replace sickles in farming until the 16th century, but the earlier scythes were still thought to mow down the fields faster than sickles would. Perhaps the smaller tool was just too beneficial in too many circumstances to be replaced entirely.

Figure 12. Neolithic rock engraving depicting scythes, Vingen, Norway.

Figure 13. Early Medieval scythe blade from the Merovingian site Kerkhove-Kouter in Belgium.

Figure 14. German peasant with a scythe from 850 AD

Figure 15. Four of 12 stained glass roundels depicting the "Labours of the Months" (1450-1475)

The ceiling from the studietto (private study) of the Medici Palace in Florence, and apart from the famous Chapel of the Magi by Benozzo Gozzoli, still in situ, is the only element of the palace’s magnificent interior to have survived, and was created for Piero de’ Medici in the 1450s. The ceiling is by the sculptor Luca della Robbia (1399-1482), and consists of twelve roundels depicting the Labours of the Months. It employs the technique of tin-glazed terracotta, developed by della Robbia around 1430 for architectural sculpture (Nuttall 2013). Unlike popular della Robbia relief sculptures, these roundels boast naturalistic paintings in shades of white and blue, colours achieved through an experimental method seldom replicated. The edges of each roundel are adorned with sculpted leaf patterns, subtly detailed in low relief, offering a textural contrast to the smooth, painted centers (Hatfield 1970)

Figure 16. June from the 12 Labours of the Months from the Medici Palace.

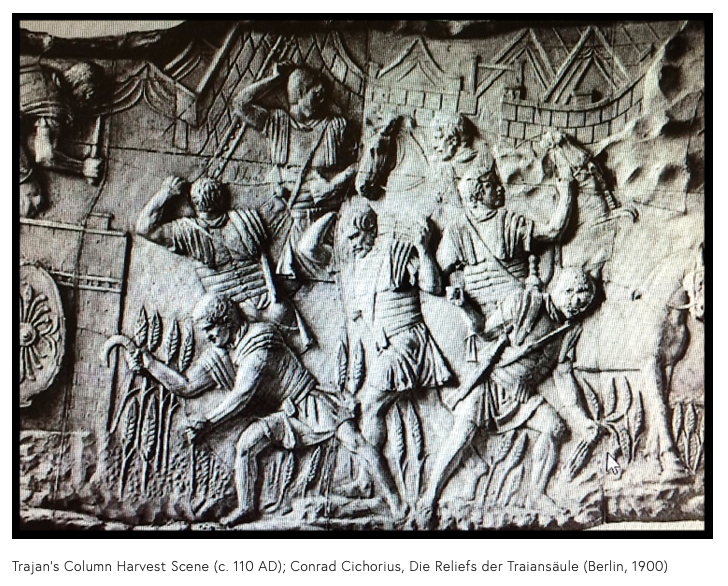

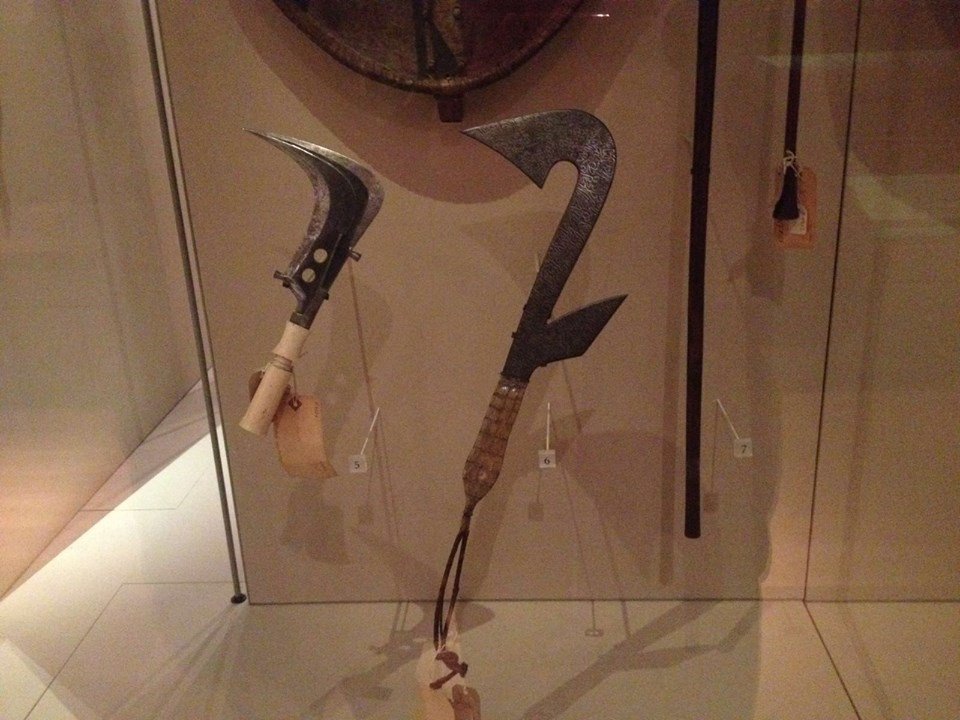

The word "falx" originally meant "sickle," but as technology advanced, its meaning came to encompass any tool or weapon with a curved blade. As it was used in Latin, the sickle was falx messoria, and the scythe was falx foenaria. The falx tool was later used as a weapon and described in Ovid's Metamorphosis as more of a falcata (ensis falcatus), a curved sword from pre-Roman Iberia (Figure -)(Silva, 2013; Fulgosio, 1872).

Figure 17. Roman monument commemorating the Battle of Adamclisi clearly shows Dacian warriors wielding a two-handed falx romphaia (Photo by Cristian Chirita)

Figure 18. A historic monument in Județul Constanța (Photo by Cristian Chirita)

Figure 19. Dacian weaponry including a falx (top) (exhibited in Cluj National History Museum -"Getai Gold & Silver Armor". Romanian History and Culture

Figure 20. Iberian falcata - necrópolis de Los Collados, Córdoba (photo by Ángel M. Felicísimo)

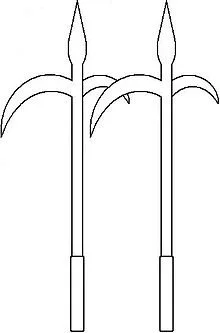

Other variations also became weapons in different countries, and a list includes, but is not limited to, the:

Even though these tools had been converted to weapons, they still continued to be used as farming equipment.

A Bit of Both

The Khopesh (Sickle-Sword)

Originating in Western Asia, particularly Mesopotamia, the sickle-shaped sword was adopted and adapted by the Egyptians, who transformed it from a type of curved battle axes into a distinctive weapon favored in both warfare and ceremony. Characterized by its pronounced curve and it’s sharp inner and outer edges, the blade’s form echoed the agricultural sickle even as it served martial purposes, and its visual impact made it ideally suited to symbolic use; in Egyptian art the sword became closely associated with pharaonic authority, military prowess, and the divine right to rule, appearing repeatedly in statues, reliefs, and murals as an emblem of power. Its name may derive from an Egyptian word meaning "knee" or "leg," a possible linguistic reference to the ox leg historically used in sacred offerings, linking the weapon not only to combat and rulership but also to ritual practice and the broader symbolic language of life, sustenance, and sovereignty.

In Egyptian mythology and culture, the sickle was, of course, crucial for agriculture (harvesting grain for daily bread/beer, afterlife sustenance) and symbolised fertility (with the growth of agriculture), royal power, and protection, appearing as a ceremonial tool for pharaohs, especially during festivals, and a tool for gods like Horus or Set. It also connects the khopesh (sickle-sword) to the kings by using it in festivals and rituals, as it has long symbolised power.

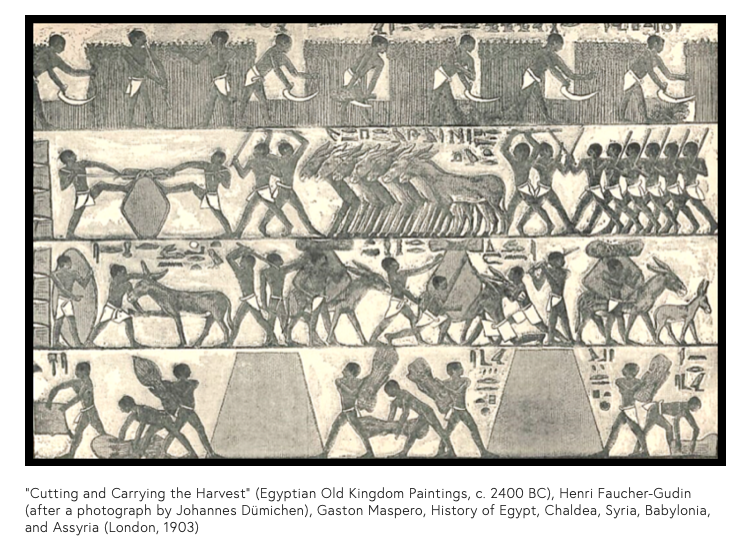

Significance in Daily Life & Afterlife

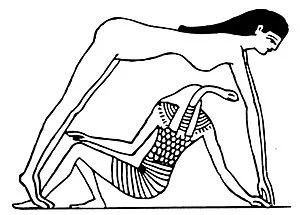

Agriculture was central to Egyptian life, providing the staple grains that underpinned daily sustenance and the production of bread and beer—the dietary cornerstones of ancient society. Wooden sickles fitted with flint blades as standard agricultural tools, also found a place in funerary practice: they were placed in tombs and painted on the tomb walls in the hands of their afterlife servants so the deceased might continue to harvest divine crops in the afterlife, or use them as protective implements to ward off hostile spirits. As objects and motifs, sickles carried rich symbolic weight, evoking the cyclical rhythms of life and death, the renewal of the harvest, and the promise of abundance; this symbolism is reflected in artistic and religious imagery, where deities such as Horus are sometimes portrayed in the role of reaper, linking royal and cosmic order to the fecundity of the land.

Figure 27. Old Kingdom Painting

Royal & Divine Connections

Ornate sickles, like those from Tutankhamun's tomb (gilded wood, glass blades), were used in festivals (Peret) and as symbols of royal duty, linking kings to agricultural prosperity. Peret or Proyet was the growing/planting season that typically took place between November and March as the second of the three agricultural seasons after Akhet (the inundation/flooding season - summer) and before Shemu (the harvest/low water season - spring/summer), and peret means the "Season of Emergence". Also called the black season, when the Nile's floodwaters receded, leaving the fertile black silt, farmers ploughed and sowed seeds (like wheat, barley, flax, vegetables) for the growing season, focusing on nurturing new life in the enriched land. Which is definitely something people would want to celebrate, and they’d be grateful to the pharaoh, since it was part of his divine duties to keep the land running according to its proper cycles.

Horus, depicted as the "divine husbandman," holding a sickle to symbolise his power over germination and harvest. Some people think that another deity possibly associated with the festival and the beginning of the planting season was the goddess Satis, consort of Khum, who is the goddess of the flood. But I couldn’t find any direct connections between them. Additionally, a sickle-like object or tool might be associated with Set, god of disorder, perhaps in conflict or ritual, though Set is more known for his role in battling Apep.

Appearances in Myth

Many of these myths are contradictory and difficult to sort out, so I'm writing the versions that I enjoy.

If Western mythology can say anything, we can say that we tend to 'emulate' older cultural traditions that are deemed worthy. Not automatically a bad or harmful thing, this can help us trace our roots, and the roots of the everyday things we use. Going back into the deep past, one of the longest through-lines (possibly) begins with the story of Gaia, her son/husband Ouranos (or Uranus), and their son Cronus from Ancient Greece, and, based on name’s etymology, possibly its predecessors (Beekes, 2009).

CRONUS/ KRONOS

Gaia, the primordial iteration of the Earth and Ouranos, the sky, had a heap of children, with the youngest being Cronus/Kronos. The Titan God of the Harvest is a marker of time passing, changing seasons, and the yearly reaping (Nilsson, 1951: 122-4). The short version goes as such...

Gaia created her husband, Ouranos, and fearing that he would be supplanted by one of his children, he ate the ones who would become known as the Titans after locking up the more monstrous of his and Gaia's children. Gaia wasn't too happy about this, so she created the harpe (a combination sword-sickle), or more traditionally, a sickle out of either flint or grey adamantine (diamond) for Cronus to castrate and possibly kill his father to save his siblings. He did. Ouranos was sliced apart after being castrated, and Cronus then "threw them into the sea behind him; and with them he also threw away the sickle at Cape Drepanum" (Apollodorus, Library 1.1.4, Hesiod, Theogony 159ff, & Pausanias, Description of Greece 7.23.4).

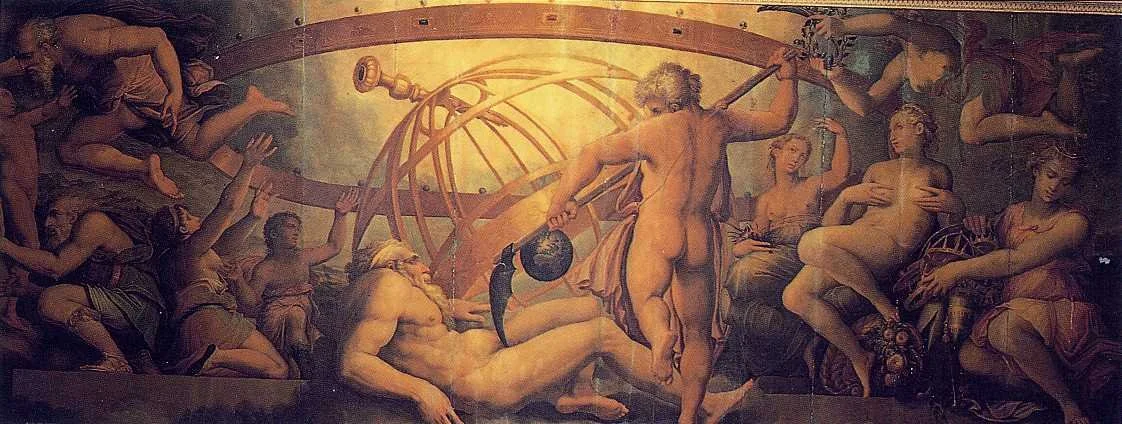

Figure 28. The Mutilation of Uranus by Saturn: fresco by Giorgio Vasari and Cristofano Gherardi, c. 1560 (Sala di Cosimo I, Palazzo Vecchio)

Once Ouranos was out of the way, Cronus became the ruler of the Titan Age, and after learning from Gaia that just like Ouranos, one of his children would overtake him, he ate them one by one (Hesiod, Theogony).

Figure 29. Peter Paul Rubens of Cronus devouring one of his children (between 1636 and 1638)

No one was happy about Cronus eating his and Rhea's children (either whole or in pieces), so after Rhea gave birth to her youngest son, Zeus, on the island of Crete, she gave Cronus the Omphalos Stone, which he promptly swallowed. After growing up in Gaia's care, Zeus came back with an emetic (vomit-inducing poison) that either Metis or Gaia gave him, which made Cronus throw up all of his siblings and the stone. With the aid of his siblings, the three Cyclopes, and the Hecatoncheires, Zeus' team was able to defeat Cronus and throw him into Tartarus (Apollodorus,1.2.1; Hesiod, Theogony). This brought about the generation of Gods, the Olympian Age.

It's not clear whether this particular sickle ends up being the same weapon that was given to Perseus by Hermes when he went to kill Medusa, but it seems like an interesting continuation, especially because Gaia made the blade to kill monstrous beings (Apollodorus, Library 2.4.2). If it was the same one, it was either thrown away by Cronus after defeating Ouranos or was perhaps taken away after Cronus was defeated. Also, as these take place in a mythical setting, timing isn't specifically defined, so, other than the generational changes, we're not very sure which events were taking place in which order. The story of Perseus, however, did take place during the Olympian Age, as evidenced by the appearance of Hermes and Hera.

Figure 30. "Perseus with the Head of Medusa" depicts Perseus, armed with a harpe sword, as he beheaded Medusa.

Zeus also used his adamantine (diamond) sickle to fight Typhon (born of Gaia, who was supposed to supplant Zeus), which didn't work out well for him, at first...

"Zeus pelted Typhon at a distance with thunderbolts, and when they were close, the god struck him down with an adamantine sickle. However, Typhon wrested the sickle from him, severed the sinews of his hands and feet, and, lifting him on his shoulders, carried him through the sea to Cilicia in Asia Minor and deposited him on arrival inside the Corycian cave." -(Apollodorus, Library 1.6.2)

Even before the latter ties to "monster" slaying, the sickle that Gaia created was known as a divine weapon. It may have been indestructible with divine magic for 'divine slaying' and essence scattering. With the hoops that seemingly have to be jumped through for the ability to kill a God, it seems like only something that Gaia created can destroy someone Gaia created. This seems tied to the idea of homoeopathy, but that's a whole other story.

*Side note: I find it interesting that it's the youngest child that does the saving, sure it doesn't always end well for them, but still*

Because Greece and Rome liked to consolidate Gods internally and with any outside groups that they connected with or conquered, researchers see their favorite Gods being combined with others. Most of these Gods have only slight connections based on what they rule over/represent, and/or who their parents were. They aren't all depicted with the sickle tool, so I'll move along as quickly as possible.

Figure 31

Classical authors often compare the Greek version of Cronus to:

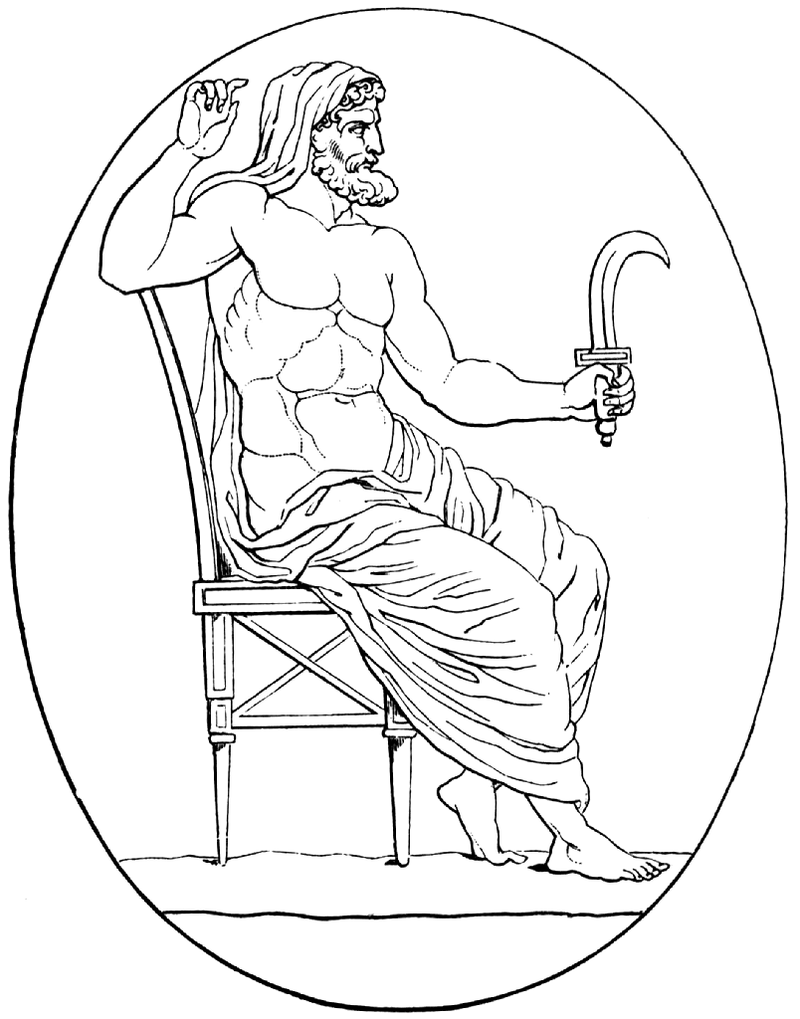

Roman ~ Saturn

Like his Greek equivalent, Saturn, or Sāturnus in Latin, was the ruler of the Gods during the Golden/Titan Age. Varro, in De lingua Latina 5.64, says that the name Sāturnus came from satus, meaning "sowing", but even if this isn't etymologically connected to the Titan's name, the meaning still does. He was worshipped as the Titan of Capitol, wealth, agriculture, liberation, and time, so to the Romans it only made sense to conflate him with the Greek God of the Harvest and even to the Orphic Greek God Chronos/Khronos (but I'll talk about him later) (Hesiod; Ovid; & Macey,1994 & 2013). Also, he's one of two versions shown holding a sickle; the other is from the Hurrian and this is the Saturnus that the holiday Saturalia celebrates wherein slaves are made citizens, if only for a time, and everyone drinks - a lot..

Figure 32

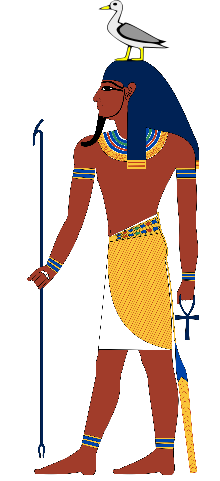

Egyptian ~ Geb

The God of the Earth, Geb, was also the God of vegetation, fertility, earthquakes, and was the father of snakes (the word for snake was s3-t3– "son of the earth" - from coffin lid texts). Geb, Seb, or Keb was often signified with a snake head or a goose (Wallis Budge, 1904; Wilkinson, 2003). The snake is also one of Cronus' symbols, which also includes grain, a sickle, and a scythe. This flips the roles males and females played in the creation myths, with Geb as the Earth and Nut as the Sky.

Figure 33

Mesopotamian ~ Elil - Sumerian:𒀭𒂗𒆤 (worshipped by the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Hurrians)

God of wind, air, earth, and storms.

Worshipped in Sumer as more of the King of all the other Gods, a creator, and "as a benevolent, fatherly deity, who watches over humanity and cares for their well-being" (Kramer, 1963: 119). This doesn't match with how the Greeks saw or worshipped Cronus, but he created a farming tool, though is was described as more of a pick-axe or a hoe (Hooke, 2004 & Green, 2003: 37).

Hurrian mythology/Hittite ~ Kurambi

Kumarbi is a major Hurrian creator/underworld god, the "father of gods," known from Hittite adaptations (the Kumarbi Cycle) where he overthrows his father Anu, fathers the storm god Teshub (Hittite Tarhun), and then tries to prevent Teshub's kingship, famously by fathering the stone giant Ullikummi, a story echoing Greek myths of divine succession. He's associated with prosperity, the underworld, and fertile earth, a deposed king whose myths detail cosmic power struggles. In the Song of Kurambi, the title character bites off his own genitals and spits out semen, creating three new Gods. The weather god Tešub was cut out of Kurambi, making him Kurambi's son, and it is he who overthrows him. Upon reading the stories in the Song of Kumarbi aka Kingship in Heaven tablets, scholars pointed out the similarities to the stories about Cronus (Leick, 1998: 106; West, 1966: 18-31; Kirk, 1970: 214-20; & Güterbock, 1948). Also in the Song of Ullikummi, 'Teshub' uses the "sickle with which heaven and earth had once been separated" to defeat the monster Ullikummi, establishing that the "castration" of the heavens by means of a sickle was part of another creation myth. The origin was a cut creating an opening or gap between heaven (imagined as a dome of stone) and earth enabling the beginning of time (chronos) which ties it to Latinate history and the earlier Greek Mythology.

The surviving copy of the Kumarbi Cycle is separated into many parts, three of which are still preserved. The tablets found were written in Hittite between 1400 BCE and 1200 BCE. The story was probably originally recorded during the height of Hurrian civilization around 1500 BCE.

Figure 34. A possible representation of scenes from the Song of Ullikummi on the golden bowl of Hasanlu 800 BCE

Ugaritian/Canaanite ~ El - ʼĒl(orʼIl,Ugaritic:𐎛𐎍

Figure 35. Gilded statue of the Canaanite supreme deity El (c. 1400–1200 BC) from the site of Tel Megiddo. El is identical to the Ugaritic god Ilu, whose name is considered to be the cognate of the word "Ilah", which later becomes Allah (Al-Jallad 2025).

In the Sanchuniathon, the Philo of Bybos, aka Herennius Philon, a Phoenician historian who lived in Ancient Greece in 64-141 CE, Ēl or Elus is the sun of the Earth and Sky, hence Cronus (Miller, 1967). But other than the other combination to the Star Saturn, that's where the similarities end. This is also made more complex because the only reason we have the Sanchuniathon is notes by Eusebius of Caesarea, a Greek Christian who lived around 260-340 CE, who combined all of this with the Bible "history" too (though I'm not certain if it was just him).

"It was a custom of the ancients in great crises of danger for the rulers of a city or nation, in order to avert the common ruin, to give up the most beloved of their children for sacrifice as a ransom to the avenging daemons; and those who were thus given up were sacrificed with mystic rites. Cronus then, whom the Phoenicians call Elus, who was king of the country and subsequently, after his decease, was deified as the star Saturn, had by a nymph of the country named Anobret an only begotten son, whom they on this account called Iedud, the only begotten being still so called among the Phoenicians; and when very great dangers from war had beset the country, he arrayed his son in royal apparel, and prepared an altar, and sacrificed him." ~ Philo of Byblos through Eusebius.

Reported by Eusebius' Præparatio Evangelica 1.10.16 from Philo's account (the semi-legendary pre-Trojan War Phoenician) Sanchuniathon, indicates that Cronus was originally a Canaanite ruler who founded Byblos and was deified. This version gives another name as Elusor Ilus and states that in the 32nd year of his reign, he emasculated, slew, and deified his father Epigeius/ Autochthon, "whom they afterwards called Uranus" (Eusebius of Caesarea: Praeparatio Evangelica 1.10).

(Wilkinson, 2003; Caquot & Sznycer, 1980; Coleman & Davidson, 2015; Leeming, 2005: 60; Güterbock, 1948; Miller, 1967; Philo of Byblos).

FATHER TIME

As I mentioned earlier, Grecian and Roman philosophers connect the name Cronus with Chronos/Khronos, who was the God of time or, post-Renaissance, Father Time (Macey, 2013). As described in the Orphic poems, the unaging Chronos was "engendered" by "earth and water", and produced Aether and Chaos, and an egg, which produced the hermaphroditic god Phanes, who gave birth to the first generation of gods (West, 1983:178). Pherecydes of Syros (6th c. BCE) later described Chronos as the ultimate creator of the cosmos, Zas (Zeus) and Chthonie (the chthonic - concerning, belonging to, or inhabiting the underworld) joining him as the three eternal principles (Kirk, Raven, and Schofield, 1984: 24, 56).

The much earlier Athenian philosopher Plato (400s-300s BCE) was the earliest mention I could find of an explanation for the direct conglomeration of Cronus and Father Time. In one of his dialogues (Cratylus), Plato points out that the name Κρόνος (Kronos) means "the pure and unblemished nature of his mind". This doesn't make a lot of sense until reading that, also according to Plato, both Cronus/Kronos and his wife Rhea (rhoĕ) were named after streams, one of which was Chronus.

The Roman philosopher Cicero (1st c. BCE) was among the earliest to record this connection, after Plato. He and Plutarch (in the 1st c. CE) based it on the assumption that Cronus was synonymous with Chronos or χρόνος, meaning time (Plutarch, On Isis and Osiris, 32). This link was made not only via the name, but also because Cronus was the God of Harvests, which linked with the maintenance of the course and cycles of seasons and periods of time (Cicero, De Natura Deorum 25; Lindell, 1940; Plato, Cratylus, 402b; Proclus, Commentary on Plato's Cratylus, 396B7). This is also connected to the name Saturn, as its implied meaning is that, because he was devouring his children, Saturn/Cronus/time also eventuallly devours the ages (Dronke, 2001: 316).

There are, however, more modern academics who disagree with this interpretation, such as H.J. Rose in 1928 and Janda in 2010. It was only since the Renaissance that we were able to access these newer pieces of art, as during the Dark Ages, there wasn't much documentation of mythological stories, whether in text or in art. According to H.J. Rose, the etymology "fell short", but Janda gave further explanation by offering an Indo-European etymology of "the cutter" (Rose, 1928: 43). The root*(s)ker-"to cut" from the Greek κόβω (kovo) and κουρεύω (kourévo) that connects to the English 'shear'. This may have been motivated by Cronus's characteristic act of "cutting the sky" or the genitals of the anthropomorphic sky, Ouranos (Janda, 2010).

This, the Western version of time personified, Father Time, first really appears in the Renaissance, with a scythe and an hourglass. In some mythology, this is explained by Father Time becoming a companion of the Grim Reaper, personification of Death, and taking his scythe (Hall, 1996: 119-20). You'll notice that, though the scythe is one of Cronus's symbols, it was not THE original tool he used to defeat his father. [Almost like the myths were evolving with the changing times and technological advancement.] Father Time may also have had a snake-like attribute, with its tail in its mouth (also reminiscent of the Viking world serpent, Jormungandr), and the Ouroboros an ancient Egyptian symbol of eternity that brings almost all of the conglomerated Gods together.

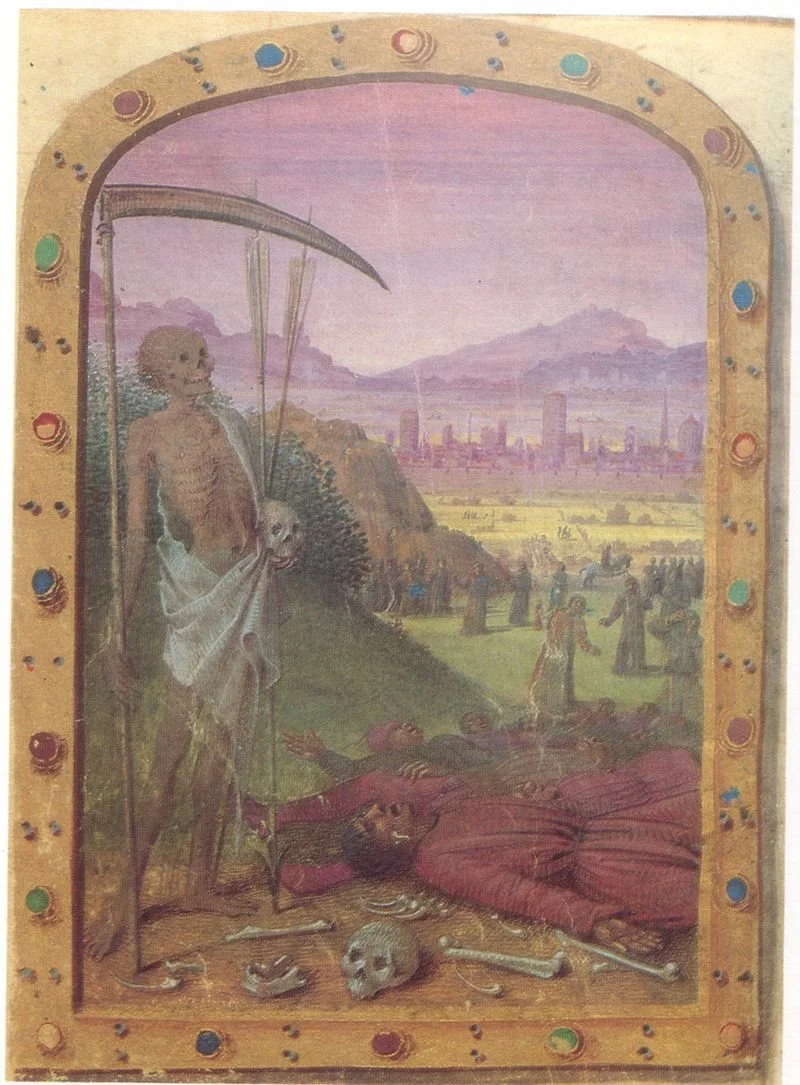

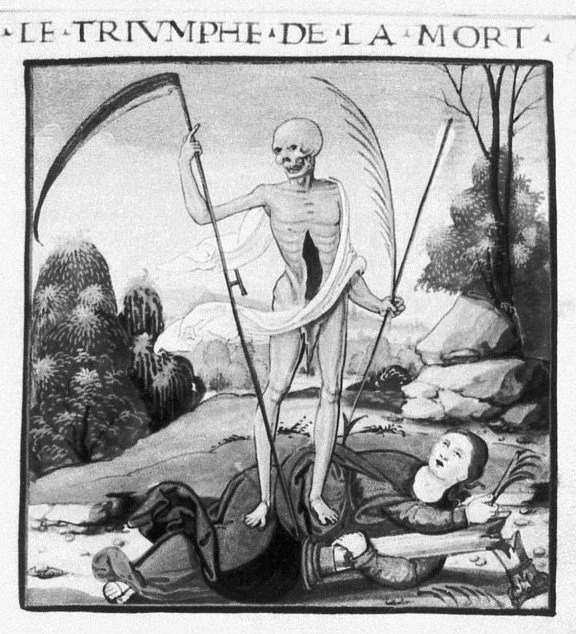

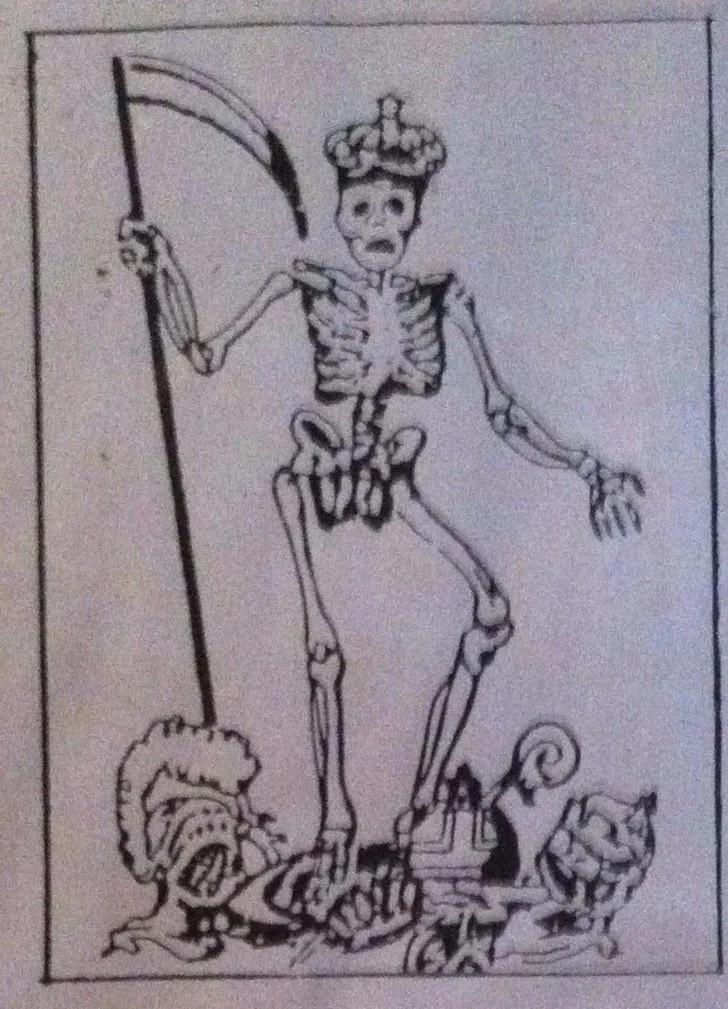

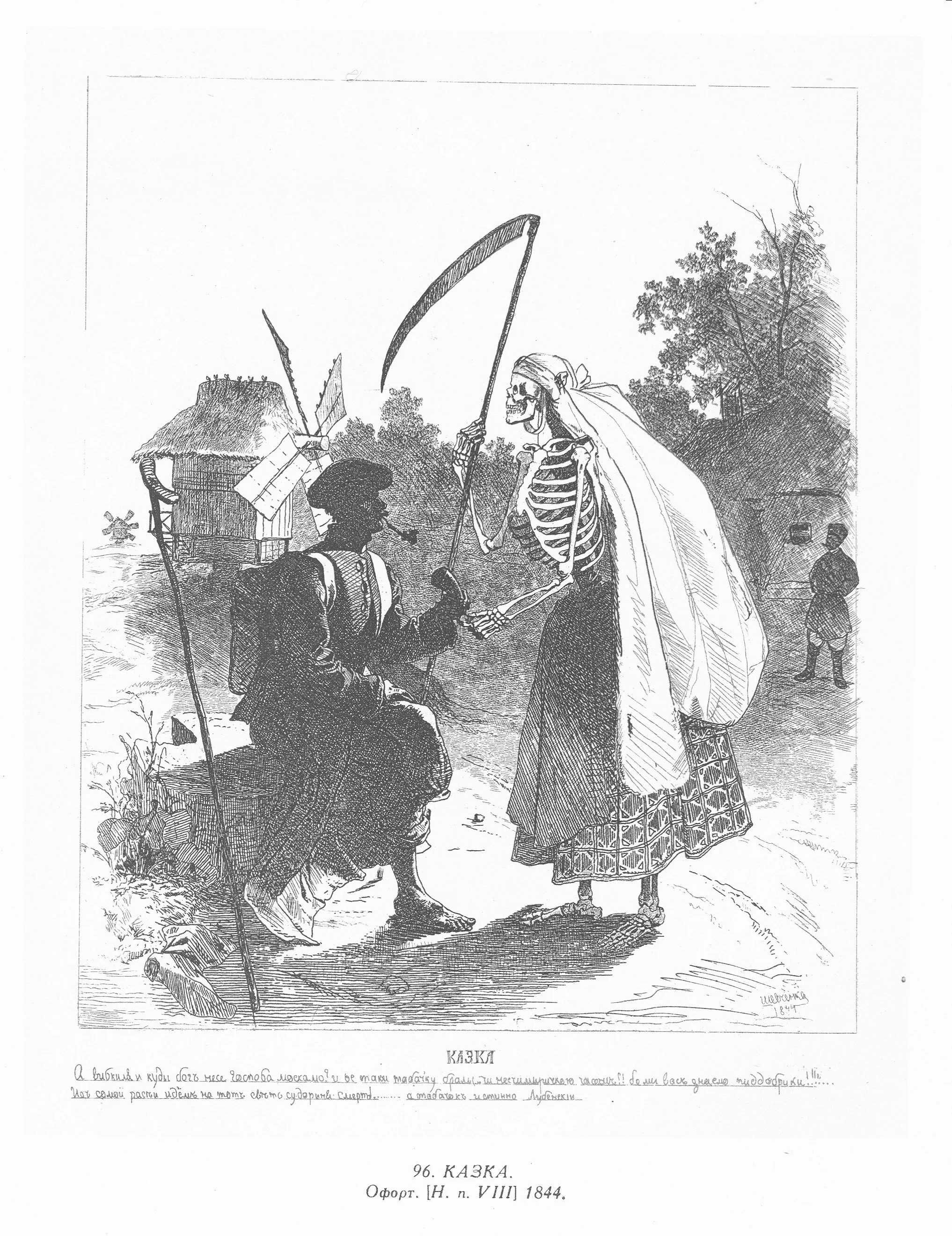

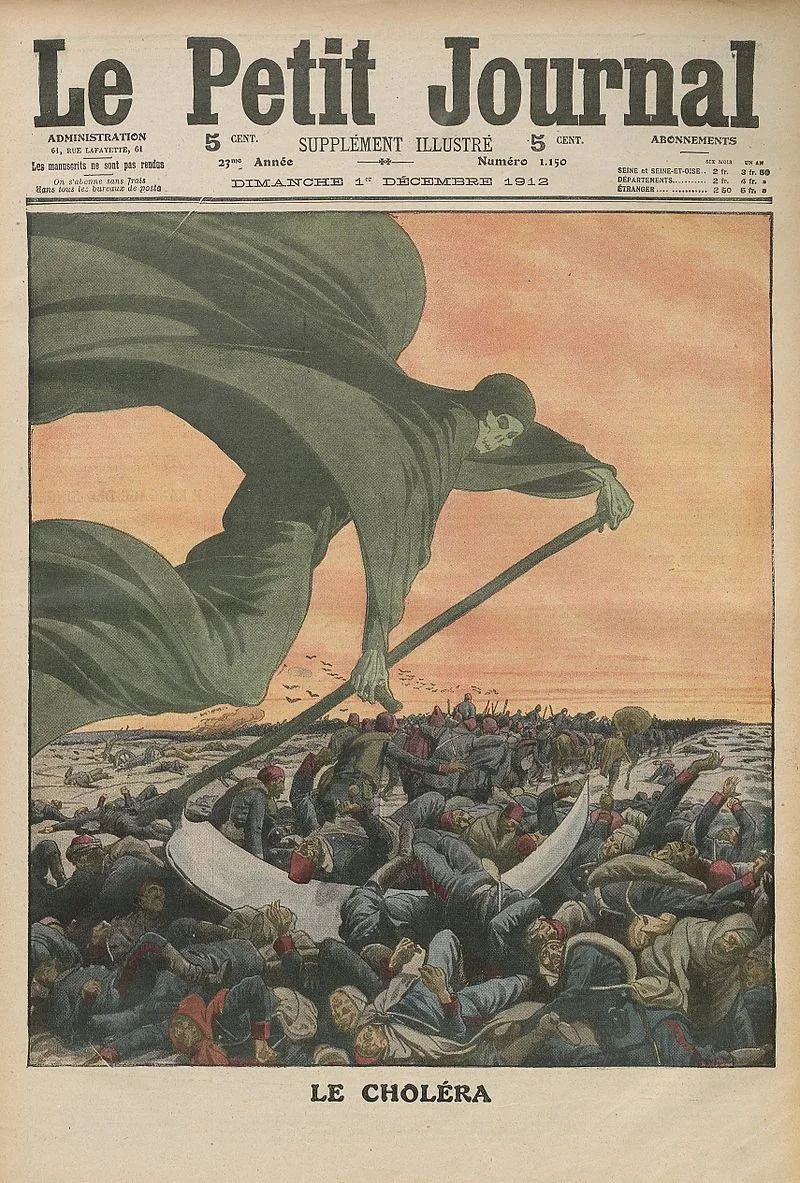

DEATH/ THE GRIM REAPER

Not all of the pieces I found had the scythe, so I am using the photos that are or are examples of Death from not directly "western" culture, especially Hel from Scandinavia (1889 by Johannes Gehrts ~ Figure -) and यम राज, Yama Rājā from Hinduism with many different versions of reapers (from Kurnool in the 16th-17th c.~ Figure -) as they are both Gods of death and are carrying staffs. [I own none of these images; they were all found on the Wiki page for 'Death-personification'.

These depictions of walking skeletons is most likely the image that most of us are familiar with. As the scythe was for reaping/harvesting crops, we no longer question its appearance with the Reaper (the name given for its reaping of souls). For a time (12th-13th c. BCE) in the Levant, Death was even personified as the Canaanite God Mot, the son of El. It's not a direct tie to earlier mythological discussion, but it does show family ties and the continuation of traditions (Cassuto, 1962).

The 'Angel of death' is often shown with the wings and the hourglass of Father Time and was thus an early Renaissance addition (Hall, 1996). Most western cultures also eventually, generally, switched over to Death being portrayed as the Grim Reaper, but there are examples of earlier mythology bleeding through.

Let me show you another painting...

Figure 61. "Death" (Nāve; 1897) by Janis Rozentāls

Finally, getting to the cover image for the blog, this, by the Latvian painter Janis Rozentǎls in 1897, is obviously far after the Renaissance, but it connects with the ancient and the modern. By now, people have moved slightly further away from the Black Plague (as shown in the second painting down on the left side), and Death is shown as more 'alive', and all the subjects are in a calm wooded area. Like the previous two examples, Death is shown as a female angel, or, in the early mythology of Latvia, as the young woman named Giltinė. The other major difference is that Death is holding a sickle, not a scythe, harkening back to the original Father Time and the tool he used to defeat a purveyor of death. I can't speak to the artists' ideas, but this painting seems less intimidating. A white-gowned figure with a mother and child almost evokes a sense of peace rather than the fear that accompanies the unknown. Especially without a large, intimidating blade looming over their heads.

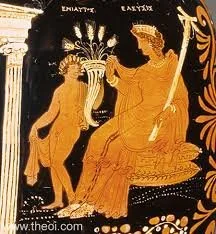

The female version also plays a role in Greek mythology, with Demeter (Ceres in Latin), who is sometimes called Khrysaoros, meaning 'Lady of the Golden Blade', after the gold sword or sickle she is sometimes depicted with ("DEMETER ESTATE & ATTRIBUTES - Greek Mythology"). Her position seems to almost supplant Cronus, because she was the Goddess of agriculture and the harvest, and she presides over grains and the fertility of the earth, while also being identified with a snake. Another connection is that although she was most often referred to as the goddess of the harvest, she was also the goddess of spring, sacred law, and the cycle of life and death ("Demeter - Facts And Information On Greek Goddess Demeter", 2014).

Figure 62. Antoine Watteau, Ceres (1717/1718); Samuel H. Kress Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Figure 63 & 64. Demeter/Ceres holds a sickle in her right hand; Smithsonian Art Inventory Sculptures - Fredericksburg, VA

Figure 65. The goddess Demeter (aka Ceres). Her symbolic tokens are the scythe and the sheaf of grain in her hair. (Pinterest)

Figure 66. Plutus and Demeter, Apulian red-figure loutrophoros (c. 4th BC), The J. Paul Getty Museum.

There is another death connection in there too, Demeter’s daughter Kore (maiden)/Persephone. She is often thought of as the goddess of Spring, but it’s really her mother that causes seasons when her Persephone has to return to the underworld and to her husband Hades in the Fall until Spring when she returns. She was worshipped in mystery cults, so we don’t know much about the actual rituals that took place, but she was also called “Dread Persephone” and if she was also maiden, a simple way of not calling on scary gods/goddesses, then she must have been truely terrifying to be on the wrong side of, being less talked about than Hades Lord of the Underworld.

[For more I suggest Overly Sarcastic Productions episode on Hades and Persephone, highly mysterious.]

Odin

Moving further into Western Europe, Odin was the head-god and a sort of trickster in Scandinavian mythology, constantly seeking knowledge. In one portion of his questing tales, Odin was searching for the Mead of Poetry (Old Norse Óðrœrir, “Stirrer of Inspiration”), and he just got caught up with farmers harvesting out in the fields.

Figure 67. Odin in eagle form obtaining the mead of poetry from Gunnlod, with Suttung in the background (detail of the Stora Hammars III runestone).

At the conclusion of the Aesir-Vanir War, the Aesir and Vanir gods and goddesses sealed their truce by spitting into a great vat. From their spittle they formed a being whom they named Kvasir (“Fermented Berry Juice”[1]). Kvasir was the wisest human that had ever lived; none were able to present him with a question for which he didn’t have a satisfying answer. He became famous and traveled throughout the world giving counsel.

Kvasir was invited to the home of two dwarves, Fjalar (“Deceiver”[2]) and Galar (“Screamer”[3]). Upon his arrival, the dwarves slew Kvasir and brewed mead with his blood. This mead contained Kvasir’s ability to dispense wisdom, and was appropriately named Óðrœrir (“Stirrer of Inspiration”). Any who drank of it would become a poet or a scholar.

When the gods questioned the dwarves about Kvasir’s disappearance, Fjalar and Galar told them that Kvasir had choked on his wisdom.

The two dwarves don’t hold onto the mead for very long though, because of their taste for murder. Sometime later, they drown a giant named Gilling for fun by taking him out to sea and drowning him, then killed his wife because her crying annoyed them, this time by dropping a millstone on her head as she passed under the doorway of their house. This pisses off the giants’ son, Suttung, and he heads off for a little old-fashioned vengeance.

But this last mischief got the dwarves into trouble. When Gilling’s son, Suttung (“Heavy with Drink”[4]), learned of his father’s murder, he seized the dwarves and, at low tide, carried them out to a reef that would soon be covered by the waves. The dwarves pleaded for their lives, and Suttung granted their request only when they agreed to give him the mead they had brewed with Kvasir’s blood. Suttung hid the vats of mead in a chamber beneath the mountain Hnitbjorg (“Pulsing Rock”[5]), where he appointed his daughter Gunnlod (“Invitation to Battle”[6]) to watch over them.

Odin, the chief of the gods, who is restless and unstoppable in his pursuit of being the wisest, was angry that the precious mead was being hoarded away beneath a mountain. He wouldn’t stop until he had it for himself and those he deemed worthy of its powers.

Disguised as a wandering farmhand, Odin went to the farm of Suttung’s brother, Baugi. There he found nine servants mowing hay. He approached them, took out a whetstone from under his cloak, which of course he has, and offered to sharpen their scythes. They eagerly agreed, and were amazed at how well their scythes cut the hay. They all declared this to be the finest whetstone they had ever seen, and each asked to purchase it. Odin consented to sell it, “but,” he warned them, “you must pay a high price.” He then threw the stone into the air, and, in their scramble to catch it, the nine killed each other with their scythes. Odin then went to Baugi’s door and introducted himself as “Bölverkr” (“Worker of Misfortune”). He offered to do the work of the nine servants who had, as he told it, basely killed each other in a dispute in the field earlier that day, that of course he had nothing to do with. And as his payment, he requested a sip of Suttung’s mead. Baugi responded that he had no control of the mead and that Suttung guarded it jealously, but that if Bölverkr could truly perform the work of nine men, he would help the apparent farmhand to his desire. This is the end of the section of the story that the scythes and the wetstone were even mentioned, but the story goes on from there.

At the end of the growing season, Odin had kept his end of the bargain to the giant, who agreed to accompany him to Suttung to inquire about the mead. Suttung, however, angrily refused like, “No. Now get the fuck out.” Rebuffed, but not undaunted, Odin comes up with a cunning plan. The disguised god, reminding Baugi of their bargain, convinced the giant to aid him in gaining access to Gunnlod’s dwelling. The two went to a part of the mountain that Baugi knew to be nearest to the underground chamber. Odin took an auger out from his cloak and handed it to Baugi for him to drill through the rock. The giant did so, and a bit later Baugi said that the hole was finished, but Odin thinks that was suspiciously fast so he blew into the hole to verify, and when the rock-dust blew back into his face, he knew that his companion had lied to him. The god then told the giant to finish what he had started. When Baugi proclaimed the hole to be complete for a second time, Odin once again blew into the hole. This time the debris were blown through the hole.

He then basically says, “Later, sucker,” before turning into a snake and slithering through the hole. Once through, he turns himself into a charming young man and sets about seducing Guunlod. He won her favor and secured a promise from her that, if he would sleep with her for three nights, he can have three sips of her father’s mead. She agrees, and they set about doing it. After the third night, Odin went to the mead, which was in three vats, and consumed the contents of each vat in a single draught. Knowing that he would soon be in huge trouble, he turns into an eagle and starts flying towards home. Suttung, obviously, isn’t too happy about his mead being stolen, so he also turns into an eagle and chases him towards Asgard.

When the gods saw Odin approaching with Suttung close behind him, they set out several vessels at the rim of their fortress. Odin reached the home of his fellow gods before Suttung could catch him, who finally realizes that’s where he’s heading, and wisely decides to turn around rather than deal with literally all the gods, while Odin is vomiting up the mead he drank into vats the other gods set up along the way. Ew. A few drops, though, fall from his beak and land on Midgard, which is where all the bad and mediocre poets and scholars come from. But the good poets get a drink of the mead from Odin personally. Yet another ew.

But whether the sickles/ scythes were that important in the story, it still shows that scythe were being regularly used by farmers. The tool also appears as a grave good, proving that the Norsemen were more than raiders and pilagers.

I don't like to exclude, so let's move away from Western mythology now...

While we showed artwork signifying death in the last section (everyone has death in some form), but they weren't all connected to the sickle or scythe, so I looked for more, and found...

Kamaitachi (鎌鼬)

Figure 68. "Kamaitachi" (鎌鼬) by Masasumi Ryūkansaijin

A Japanese Yokai, this weasel spirit/demon has long sickles/ Kama as claws (人文社編集部, 2005). There are a variety of local legends about these dust devil-riding spirits, but most seem to agree that they inflict painless, bloodless cuts, as if they appeared in the wind (村上健司編著, 2000). In a few regions of Japan, they are evil gods, either as a single entity or as three separate entities (早川孝太郎, 1974). In the Western mountainous region of Kōchi and Tokushima Prefectures, Kamaitachi are the tsukumogami (a receptacle that has turned into yōkai) with the onryō (vengeful spirit) of a discarded or forgotten sickle (京極夏彦・多田克己編著, 2000 & 人文社編集部, 2005). Meanwhile, in the East, there are legends of them as vengeful ghosts of praying mantises or beetles (京極夏彦・多田克己編著, 2008). With such a wide array of traits and origin legends, it's challenging to find meaning, especially as an outsider. Maybe it has something to do with caring for and respecting the world, along with the organisms and objects in it, because everything has its own purpose.

Conclusion

But why don't more of these particular tools show up in burials when other agricultural tools do? Unfortunately, I can't answer this question. At first, I thought that people didn't want to claim the power that the personification of Death had, but that didn't come into play until approximately the Renaissance, which was already after the scythe was associated with Father Time, and also after European cultures mostly stopped burying personal items with the dead, like with modern Christianity. So, while the tool isn't as closely connected to burial remains as the other tools I cited in my thesis, the scythe is still significant. It applies to research in both its agricultural roots and its context for mythological power. What is most poignant is how, no matter which culture it was in, the tool was adapted into a position in which its purpose of controlling nature, be it plant or human, is linked to an understanding of the nature of time and death.

Additional Reading:

There was so much that I had been searching through, and just so many rabbit holes. I've tried to keep as many links as I could in the text so you can be your little white rabbit. Otherwise, there would be way too many links to websites in this section. This whole post may have gone off the rails, but I hope that Wonderland can be a fun, educational place too.

It's not the most academic, but I definitely recommend Overly Sarcastic Productions, as they do a ton of research in mythology and history, and the videos are my faves.

Citations:

Al-Jallad, A. (2025). Ancient Allah: An Epigraphic Reconstruction. Journal of Semitic Studies, fgaf012.

Banning, E.B. (1998). "The Neolithic Period: Triumphs of Architecture, Agriculture, and Art".Near Eastern Archaeology. 61(4): 188–237. JSTOR3210656.

Beekes, Robert S. P. (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, pp. 269–270

Caquot, André and Sznycer, Maurice (1980).Ugaritic Religion. Iconography of religions. 15: Mesopotamia and the Near East. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. p. 12.

Cassuto, U. (1962). "Baal and Mot in the Ugaritic Texts". Israel Exploration Journal. 12(2): 81–83.

Christoph Sommerfeld. (1994). Gerätegeld Sichel. Studien zur monetären Struktur bronzezeitlicher Hörte im nördlichen Mitteleuropa (Vorgeschichtliche Forschungen Bd. 19), Berlin/New York. ISBN3-11-012928-0, p. 157.

Clarkson, Chris & Shipton, Ceri. (2015). Teaching Ancient Technology using “Hands-On” Learning and Experimental Archaeology. Ethnoarchaeology. 7. 157-172.

Coleman, J. A.; Davidson, George (2015). The Dictionary of Mythology: An A-Z of Themes, Legends, and Heroes, London, England: Arcturus Publishing Limited, p. 108.

Coyle, Colleen Anne. (2018). "What Grains Did Humans First Start Farming?". Quora, https://www.quora.com/What-grains-did-humans-first-start-farming.

"DEMETER ESTATE & ATTRIBUTES - Greek Mythology". Theoi. Com. (2020). https://www.theoi.com/Olympios/DemeterTreasures.html#Blade.

"Demeter - Facts And Information On Greek Goddess Demeter".Greek Gods & Goddesses, (2014). https://greekgodsandgoddesses.net/goddesses/demeter/.

Donn F. Draeger & Rober W. Smith (1969).Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts.

Dronke, Peter. (2001) Marenbon, John.Poetry and Philosophy in the Middle Ages, Leiden, The Netherlands. BRILL; pg. 316.

Emboden, W. A. Jr. (1974). Praeger Press, New York.

Fulgosio, Fernando. (1872). "Armas y utensilios del hombre primitivo en el Museo Arqueológico Nacional", in José Dorregaray (ed.),Museo Español de Antigüedades, Madrid, Vol. I, pp. 75-89.

Green, Alberto R. W. (2003). The Storm-God in the Ancient Near East. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Güterbock H. G. (1948), The Hittite Version of the Hurrian Kumarbi Myth: Oriental Forerunners of Hesiod, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 52, No. 1, p. 123–34.

Hall, James. (1996). Hall's Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, (2nd edn).

Hatfield, Rab. “Some Unknown Descriptions of the Medici Palace in 1459.” The Art Bulletin 52, no. 3 (1970): 232–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/3048729.

Heizer, Robert F. (1951). "The Sickle in Aboriginal Western North America". American Antiquity. 16(3): 247–252. doi:10.2307/276785. JSTOR276785.

Hooke, S. H.(2004). Middle Eastern Mythology, Dover Publications.

Janda, Michael. (2010). Die Musik nach dem Chaos, Innsbruck. p. 54-56.

Kirk, G.S. (1970). Myth: Its Meaning and Function in Ancient and Other Cultures. Berkeley and Los Angeles. p. 214-20.

Kirk, G. S., J. E. Raven, M. Schofield. (1984). The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts. Cambridge University Press; 2nd ed.

Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Leeming, David (2005).The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 118.

Leick, Gwendolyn. (1998). Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology. Routledge, p. 106.

Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert(1940) [1843], "ἀκήρ-α^τος", A Greek-English Lexicon (revised and augmented throughout by SirHenry Stuart Jones with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Macy, Samuel L. (1994) entry on "Father Time," in Encyclopedia of Time (Taylor & Francis), p. 208–209.

Macey, Samuel L. (2013). Encyclopedia of Time. Routledge. p. 209.

Miller, Patrick D. (1967). "El the Warrior".The Harvard Theological Review. 60(4): 411–431. JSTOR1509250.

"Mythical Objects - Greek Mythology Link". Maicar. Com. (1997). http://www.maicar.com/GML/MythicalObjects.html.

Nilsson, Martin P. “The Sickle of Kronos.”The Annual of the British School at Athens, vol. 46, 1951, pp. 122–124. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30096779.

Rose, H.J. (1928). A Handbook of Greek Mythology:43.

Scheuerman, Richard. (2017). "Ancient Grains & Harvests (Part 1) — Palouse Heritage".Palouse Heritage, https://www.palouseheritage.com/blog/2017/2/10/ancient-grains-and-harvests-part-1.

Silva, Luis. (2013). Viriathus and the Lusitanian Resistance to Rome 155-139 BC.

Unger-Hamilton, Romana (July 1985). "Microscopic Striations on Flint Sickle-Blades as an Indication of Plant Cultivation: Preliminary Results".World Archaeology. 17(1): 121–6.

Unger-Hamilton, Romana (1989). "The Epi-Palaeolithic Southern Levant and the Origins of Cultivation".Current Anthropology. 30(1): 88–103.

Wallis Budge, E. A.(1904). The Gods of the Egyptians: Studies in Egyptian Mythology. Kessinger Publishing.

Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003).The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames and Hudson. p. 105–106.

West, M.L. (1966). Hesiod Theogony p. 18-31.

West, M. L. (1983), The Orphic Poems, Clarendon Press.

Works, Martha A. (1987). "Aguaruna Agriculture in Eastern Peru".Geographical Review. 77(3): 343–358. doi:10.2307/214125. JSTOR214125.

人文社編集部 (2005).諸国怪談奇談集成 江戸諸国百物語 東日本編. ものしりシリーズ. 人文社. p. 104. ISBN978-4-7959-1955-6.

村上健司編著(2000).妖怪事典[Specter encyclopedia].毎日新聞社. p. 115. ISBN978-4-620-31428-0.

京極夏彦・多田克己編著(2000).妖怪図巻.国書刊行会. pp. 181–182. ISBN978-4-336-04187-6.

京極夏彦・多田克己編著(2008).妖怪画本 狂歌百物語.国書刊行会. p. 294. ISBN978-4-3360-5055-7.

早川孝太郎 (1974).小県郡民譚集.日本民俗誌大系.第5巻.角川書店. p. 91. ISBN978-4-04-530305-0.