Heru-Who?

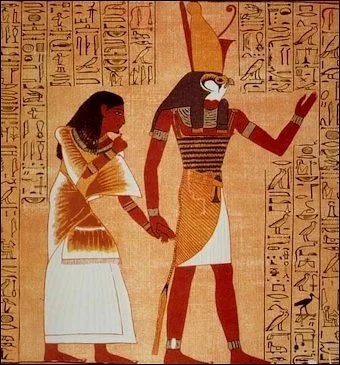

Figure 1. Horus

Why doesn’t Heru-ur get more screen time? In mythology, he was THE main character, he was the hero… although maybe that was why… They couldn’t have an EGYPTIAN god be a hero, we’ll get to the Norse very soon, but even more unfortunately, is that the writers didn’t make him a strong recurring character, or very distinctive at all.

~My name is Renée, you’re listening to Detours in Artaeology. This is Heru-who?~

Now speaking of distinctive…

There is a difference between Horus the Elder and Horus the Younger, and it’s not necessarily their age. In ancient Egyptian mythology, it’s critical to understand that there is an evolution of Egyptian religious symbolism and the intertwining narratives surrounding these deities. Horus, as a figure, has multiple manifestations; however, the differentiation between the two most prominent iterations is what I’ll be focusing on—Horus the Elder and Horus the Younger—as the former connects to the god that the stargate villain is based on… at least his name. These differences particularly matter in the context of their familial lineage, roles in mythology, and their cultural significance within Egyptian society.

Figure 2 . Name of Horus

Horus the Elder was often recognized as the original Horus and was mainly known as Heru-ur, which is the Egyptian name(Hrw Wr, Har-wer, Haroeris), surprisingly an Egyptian God Gou’ald actually named after the Egyptian name. He signifies a primordial god associated with the sky and kingship. He’s one of the earliest known deities in the Egyptian pantheon, making his significance foundational to subsequent religious developments (Porceddu et al. 2018). Horus the Elder (really in general) is frequently depicted as a falcon or with a falcon's head, symbolizing the celestial aspect and his dominion over the heavens (Hany & Elweshahy 2018). His associations extend to protective elements, as he was considered responsible for safeguarding the pharaoh and ensuring order and stability within Egypt, traits deeply ingrained in the narrative of divine kingship (Elsayed, 2019). While the name Heru-ur (Hrw Wr, Har-wer) meant "Horus the Elder", it could also translate to "Horus the Great".

Heru-ur was a very ancient sky god, and his face was believed to be the face of the sun. He was depicted as a falcon or a falcon-headed man and was considered one of the oldest deities in Egyptian mythology. His role evolved over time, and he became the patron god of the pharaohs and a symbol of their divine right to rule. (Hill 2008)

In contrast, Horus the Younger—often simply referred to as Horus—is primarily recognized as the son of Osiris and Isis, embodying the themes of resurrection and battles against chaos, principally represented by his uncle Seth. His narrative is central to the myth of Osiris, where Horus the Younger avenges his father’s death, thereby symbolizing the triumph of good over evil (Hany & Elweshahy, 2018; ReFaey et al., 2019). This younger manifestation also bears significant implications for the concept of kingship. Horus the Younger was perceived as the rightful heir to the throne of Egypt, further intertwining his identity with that of the reigning pharaoh, who was often viewed as the living embodiment of Horus (Hany & elweshahy, 2018). This connection reinforced the notion of divine legitimacy, as pharaohs would often invoke the imagery of Horus the Younger in their royal titles, epitomising their divine right to rule.

This name was used to distinguish him from other forms of the god Horus, such as Heru-pa-khered (Horus the Child). He always had a stiff side braid in his statuettes and on multiple stela and amulets, he is depicted in a heroic way, conquer the crocodiles he is standing on (figure -).

Figure 3. Two related objects from the Egyptian collection at Glencairn Museum. Left: A soapstone amulet depicting Horus on the Crocodiles, also called a Cippus of Horus (E427). Right: A bronze statuette of Harpocrates (E1166). Both objects depict the god Horus the Child (Hor-pa-khered in Egyptian, or Harpocrates in Greek).

"Heru" in ancient Egyptian has other meanings besides "Horus the Elder" (Heru-ur), although they are closely related to the core meaning of Horus as a deity. Here are some of the key meanings and associations:

Falcon / The One Above/The Distant One: The name "Heru" (or its variations like Hor, Har, Hōros) is linked to the Egyptian word for "falcon", ḥr.w, 𓅃. This reflects Horus's association with the sky and his representation as a soaring falcon or falcon-headed man. These etymologically associated meanings of "the distant one" or "the one above/over" further reinforce this connection to the sky and his commanding position and could be connected to the notion of vision as falcons are know to be precision hunters with the fastest speed of any animal with a dive that clocks in in over 200 mph (Meltzer 2002).

Symbol of Kingship and the Sky God: Heru was a crucial deity, strongly tied to kingship and the sky. The pharaohs were considered the earthly embodiment of Horus, reinforcing his symbolic power and association with order and legitimacy.

The Falcon God and its Manifestations: The basic meaning of Heru as a falcon is central to his role as a sky god and his various forms, such as:

Heru-ur (Horus the Elder/Great): Representing the older, mature form of the god, identified as a sky god whose eyes were the sun and moon.

Heru-Behdeti (Horus of Behdet/Edfu): A protector deity who avenged his father's death, often shown as a winged sun disk.

Horus the Behdetite: Evidence for the worship or cult of Horus the Behdetite is examined from the Old Kingdom to the conquest of Alexander (Shonkwiler, 2013). This version of Horus is depicted releasing his claws into the hide of his enemies (Shonkwiler 2013). Horus the Behdetite is primarily depicted as a winged solar disk or a falcon, often shown in protective and victorious roles (Reymond, 1962; Ali, 2017; Gallardo, 2003). This deity was strongly associated with Edfu, an Upper Egyptian town, and its Graeco-Roman temple contains numerous inscriptions and depictions of Horus the Behdetite (Gardiner, 1944). The original location of Behdet, associated with Horus, was a subject of scholarly debate, with suggestions ranging from Edfu in Upper Egypt to Damanhur in Lower Egypt (Gardiner, 1944). Ancient Egyptian artists also depicted the falcon god Horus in the Delta marshes, sometimes alone or with his mother Isis (Maati, 2024). Depictions of Horus the Behdetite have been found on limestone blocks from the necropolis of Kom el-Khamaseen in South Saqqara, suggesting their origin from royal cemeteries (León & Autuori, 2024).

Heru-pa-khered (Horus the Child/Younger): Depicted as an infant suckled by Isis, symbolizing youth and new beginnings, and later Harpocrates. Horus the Child (Harpocrates): The Horus child is mentioned in various texts from the Old Kingdom, including the Pyramid Texts and medical texts (Sandri 2006). who was transformed into the Greek god Harpocrates after Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in 331 BCE.This form of Horus, known by the Greeks as Harpocrates, was considered the most beloved of all Egyptian deities (Piankoff & El-Khachab, 1971). Harpocrates is identified as the divine boy, son of Osiris and Isis, and the avenger of his father (Piankoff & El-Khachab, 1971).

Horus of Letopolis: This version of Horus could adopt animal appearances such as a shrew mouse and an ichneumon, the animal that is offer depicted killing and eating Apep (Apophis) (Pichel, 2016).

Her-em-akhet (Horus in the Horizon/Harmachis): Associated with the dawn and the early morning sun, often represented by the Great Sphinx of Giza. The "Dream Stela" (or Sphinx Stela) is located between the paws of the Great Sphinx, tells the myth of a dream experienced by Prince Thutmose (before becoming Thutmose IV), the 8th pharaoh of the 18th dynasty in the New Kingdom, when he fell asleep near the statue. (Piankoff 1932).

In his dream, the Sphinx, spoke to him and introduced himself as the deity Hor-em-akhet (Horus in the Horizon). The Sphinx was depressed at its dilapidated state, complaining of being covered by desert sands (according to History.com). It promised Thutmose that it would help him become pharaoh if he cleared the sand and restored the statue (which he was likely not in line for since he had an older brother Amenhotep who likely, luckily only for Thutmose, died young. Whether the dream was literal or not, Thutmose IV did become Pharaoh and fulfilled his promise to the Sphinx. He initiated a Sphinx-worshipping cult, and the Sphinx became a prominent symbol of royalty and the power of the sun in ancient Egypt. (Piankoff 1932; Cline 2006; History.com 2018).

The Sphinx was strongly associated with the sun god Ra and with the Pharaohs, who were considered divine rulers. Some scholars suggest the Great Sphinx originally represented Horus, the protector of Egypt. The human head on the lion's body was often said to represent the pharaoh's wisdom combined with the lion's might (likely recarved multiple times by pharaohs to “fix” the face. Further, the name Horemakhet, or "Horus in the Horizon", further solidifies the link between the Sphinx and Horus as a sun god. (Lehner 1992 Sheposh 2024).

Horus-of-the-Camp: Oracle petitions addressed to the obscure god Horus-of-the-Camp date to the late Twentieth or early Twenty-first Dynasty (Ryholt, 1993).

Key Depictions and Iconography

Winged Solar Disk: One of the most prominent forms of Horus the Behdetite is the winged solar disk, often seen protecting the king (Hayes, 1946). This depiction emphasizes his celestial and protective nature (Reymond, 1962; Hayes, 1946). The sun disk with pendent uraei is also an appearance of the solar divinity Behdetite (Hayes, 1946).

Falcon: Horus the Behdetite is frequently depicted as a falcon, symbolizing his divine and powerful presence (Reymond, 1962; Ali, 2017). In the Ptolemaic Temple at Edfu, a scene shows a falcon resting on a thicket of reeds, described as "Horus the Behdetite, great god, lord of the sky, He-with-dappled-plumage" (Reymond, 1962). Some depictions include a falcon-headed Horus of Behdety in a decorated shrine (Ali, 2017).

Beetle (Api): In Edfu, Horus Behdety was also depicted in the form of a beetle, referred to as "api" (Katat, 2014).

Lion: Textual sources from Edfu describe Horus of Behdety, as known as Horus of Buto, interacting with chaos forces as a lion, trampling, retreating, smiting, and devouring (Elsayed, 2019). These texts also show Horus as the upholder of kingship legitimacy and a victorious lion over transgressors, playing a benevolent role for Egypt (Elsayed, 2019).

Figure 5. Horus of Buto

Humanoid with Falcon Head: Statuettes of the falcon-headed god Horus in Roman armor and dress are part of Egyptian collections, reflecting a concept where the Roman rulers in Egypt embodied the god Horus (Ladynin, 2022). This form suggests a transfer of the god's qualities onto the ruler (Ladynin, 2022).

Four Forms: Horus the Behdetite is noted to have at least four forms: "Horus the Behdetite," "He who ...," "beautiful of face, who is upon his great seat," and "lord of Mesen" (Gaber, 2014).

Association with Seth: Horus the Behdetite is often depicted facing "Seth of Ombos," particularly in scenes related to King Sahure's funerary temple at Abusir, where Horus the Behdetite appears among Lower Egyptian deities (Gardiner, 1944). Royal and Protective Role: Horus the Behdetite is important due to his association with the king and his role as a protector (El-Sayed, 2024). He is described as guarding individuals (Muhlestein, 2022) and is invoked as the "Protector of Re" (Reymond, 1962). In the Nag el-Hamdulab cycle, the king appears prominently as both overseer and object of a celebration involving ritual, administrative, and fiscal elements, supported by an early hieroglyphic annotation describing a ritual apparently called the "Following of Horus" (Darnell, 2014).

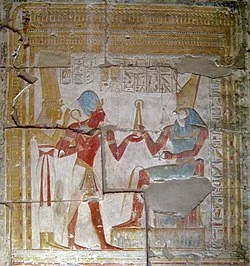

Figure 6. Scene from the Temple of Hathor (Abu Simbel, Egypt), built during the reign of Ramesses II, c. 1264-1224 BCE. Set and Horus blessing Ramesses II.

Figure 7. 13th century BC. This material was found in James Wasserman's compilation of the Papyrus of Ani: The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day.

How did the meaning of Heru influence pharaohs' roles?

The ancient Egyptian belief that the pharaoh was the earthly manifestation of the god Horus had a profound impact on the pharaoh's role and the way society functioned.

Here's how the meaning of Heru (Horus) influenced the pharaohs' roles:

Divine Right to Rule: As the living embodiment of Horus, the pharaoh's authority was divinely sanctioned. This connection to a powerful god like Horus, who represented kingship and legitimacy, strengthened the pharaoh's right to rule and helped ensure the obedience and loyalty of the people.

Maintainer of Order (Ma'at): The myth of Horus battling Set to avenge Osiris symbolized the triumph of order over chaos. The pharaoh, as Horus, was expected to embody and uphold Ma'at, the principle of cosmic order, justice, and harmony. This meant maintaining balance within society, ensuring justice prevailed, and protecting Egypt from external threats and internal disorder.

Protector of Egypt: Horus was revered as a powerful protector, safeguarding the land and its people from evil and danger. The pharaoh, as Horus, was therefore seen as a protector of Egypt, responsible for the well-being and security of the nation. This role extended to both physical defense against enemies and spiritual protection against malevolent forces.

Symbol of Unity: Horus was associated with the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. Pharaohs were depicted wearing the double crown, a symbol of a unified kingdom under the authority of Horus. This connection reinforced the pharaoh's responsibility to maintain the stability and unity of Egypt.

Intermediary between Gods and Humans: The pharaoh acted as a mediator between the divine realm and the people. By fulfilling religious duties, performing rituals, and making offerings, the pharaoh was believed to communicate with the gods and ensure their blessings for the prosperity and fertility of Egypt.

Role Model: The pharaohs were expected to emulate Horus's qualities, including wisdom, bravery, and dedication to justice. By embodying these characteristics, the pharaohs aimed to maintain the stability and prosperity of Egypt and fulfill their divine mandate.

Are there other goddesses linked to Horus besides Hathor?

Several other goddesses in ancient Egyptian mythology are linked to Horus, in various ways:

Isis: Perhaps the most well-known connection, Isis is the mother of Horus in the famous Osiris myth. She played a crucial role in protecting him from his uncle Set, and ensuring his eventual ascension to the throne. Her fierce protection of her son solidifies her role as a premier mother goddess. She is often depicted nursing the infant Horus.

Nephthys: Nephthys is the sister of Isis and Set, and also the older sister of Horus (specifically Horus the Elder). While she is the consort of Set, in some versions of the Osiris myth, she assists Isis in mourning and protecting Osiris and, later, Horus from Set's mischiefous and evil plans. She is sometimes also featured as a nursemaid to the pharaoh, who embodies Horus on earth.

Serket: Serket, a scorpion goddess, is mentioned as a consort of Heru-ur (Horus the Elder) in some texts. She is also depicted as one of the goddesses protecting the canopic chests that contained the deceased's internal organs.

It's important to remember that Egyptian mythology evolved over a long period, and the relationships between deities could and did vary widely between different regions and time periods.

The narrative of conflict between Horus the Younger and Seth not only illustrates the themes of justice and vengeance but also parallels the annual agricultural cycle of Egypt—where Horus’s victory represented the flooding of the Nile and, subsequently, the fertility of the land (ReFaey et al., 2019). The Eye of Horus, a well-known symbol associated with Horus the Younger, signifies protection and well-being, further cementing his role as a benevolent deity (ReFaey et al., 2019). Conversely, while Horus the Elder also embodies protective qualities, his representation is more directed toward the overarching jealousies associated with divine kingship and celestial mechanics.

In terms of iconography, both Horus the Elder and Horus the Younger have distinctive representations. Horus the Elder is traditionally symbolized with a sun disk, reinforcing his connection with the sky and celestial navigation, while iconographic depictions of Horus the Younger often emphasize youth and vigor, sometimes illustrated in conjunction with various symbols of royalty and strength, such as the sistrum, a traditional musical instrument linked with divine worship (ReFaey et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the geographical and cultic differences represent another layer of distinction. Horus the Elder was primarily venerated in regions such as Edfu, and his worship was often associated with the city of Hierakonpolis, regarded as one of the oldest centers of Egyptian civilization (Elsayed, 2019). Hierakonpolis, an ancient Egyptian city, translates to "City of the Falcon" in Greek. Hierakonpolis is derived from the Greek words "hieros" (sacred or holy) and "polis" (city), combined with "ak" (hawk/falcon). (Goong.com). Its ancient Egyptian name was Nekhen, which also has a related meaning related to the falcon god Nekheny (or Nekhen). The city was a major power center as a major religious and political center in Upper Egypt before the unification of the country and may have served as the first capital of a unified Egypt. The city was a during the predynastic and early dynastic periods of Egypt and was a center of worship for the falcon god Horus. Hierakonpolis is one of the most important sites for understanding the emergence of Egyptian civilization, with evidence of early temples, tombs, and ceremonial objects like the Narmer Palette (which was also discussed in the Hathor episode).

In contrast, temples dedicated to Horus the Younger were prevalent throughout Egypt, notably in places like Kom Ombo and other locations that showcased the altered dynamics of power through his association with Osiris and the divine right of kings (Hany & Elweshahy, 2018).

The continuity and evolution of the mythology surrounding Horus is attributed to legends of Horus the Elder and Horus the Younger beginning to integrate, leading to shared iconography and attributes that sometimes blurred distinctions within popular practices of worship. Many temples would invoke both versions of Horus, recognizing that they’re complementary in embodying the overarching themes of creation, kingship, and cosmic order (Hany & Elweshahy 2018; Elsayed 2019).

As scholars have noted, the duality present in the narratives of Horus reflects broader themes within ancient Egyptian theology, where the interplay of life and death, chaos and order, and the cyclical nature of existence is crucial (Hany & Elweshahy 2018). The distinction between Horus the Elder and Horus the Younger emphasizes not merely individual characteristics of divinity but also the broader socio-political context in which these entities developed and how they contributed to the fabric of Egyptian society.

Thus, while Horus the Elder and Horus the Younger share a common ancestry and thematic coherence, they embody various elements unique to their characterization, serving different roles within the narrative tapestry of ancient Egyptian mythology. The understanding of their distinct identities, demonstrated through iconography, regional worship, and mythological narratives, offers insights into the socio-cultural fabric of ancient Egypt and the religious mind of its peoples.

Figure 8. Horus offers life to the pharaoh, Ramesses II. Painted limestone. c. 1275 BCE, 19th dynasty. From the small temple built by Ramses II in Abydos, Louvre museum, Paris, France.

Artifacts

It wasn’t just the ‘Eye of Re’ that was such a big deal. Referred to as wedjat, these Eye of Horus amulets represent a human eye enhanced or combined with the characteristic markings of a falcon, and refer to the god Horus. Made in many variations for over 3,000 years, they convey wholeness and health.

Figures 9-11. Ptolemaic Period (305–30 BCE) Falcon details on wedjat (Art Institute of Chicago).

Figure 12. Eye of Horus with Nekhebet on the left with the crown of Upper Egypt and Wedjet wearing the crown of Lower Egypt

Honestly, I can’t tell the difference between them.

------------------

Worship

The worship of Horus the Elder in ancient Egypt can be traced back to predynastic times, where he was largely venerated as a significant sky and protector deity among early Egyptian communities. The earliest evidence of his worship appears in the Predynastic period, specifically associated with communities in Upper Egypt. Horus embodied the essence of kingship and was closely linked with the divine rule of pharaohs, who were regarded as "Living Horuses" throughout their reign, further solidifying his importance in the traditional religious system that governed society ("Who's who in ancient Egypt", 2000).

Horus the Elder’s worship became particularly prominent around the time of the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, with royal power consolidating under the early dynastic kings. During this time, the pharaohs adopted Horus as an emblem of their sovereignty, which instilled a sense of divine legitimacy for their reigns (Elias, 2012).

Another notable center of worship for Heru-Ur was located in the city of Hierakonpolis, one of the oldest and most important urban centers during the Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods. Archaeological findings in Hierakonpolis included significant votive objects and reliefs that indicate that the worship of Horus had deep roots tied to early kingship and the establishment of divine rule. This location also plays a crucial role in the political and religious narrative surrounding the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt as it may have been one of the first capitals (ReFaey et al., 2019).

Moreover, the localization of Horus worship varied across Egypt, with different regions celebrating him in diverse forms. In Akhmim, for instance, Horus was linked with the fertility god Min, illustrating how local traditions and deities blended with the overarching narratives associated with Horus (Elias, 2012). Temples dedicated to Horus were common across various cities, further illustrating the widespread worship of this deity throughout different historical epochs (Hafez, 2019).

In summary, Horus the Elder was worshipped from the Predynastic period through to the end of the Ptolemaic period, with his prominence stemming largely from his connection to pharaonic legitimacy, local worship practices, and the integration of regional variants. The historicity of Horus in the pantheon of ancient Egyptian religion is underscored by archaeological findings and textual evidence, reflecting the enduring nature of his veneration through millennia.

During the Old Kingdom (circa 2686–2181 BCE), worship of Horus intensified alongside the rise of monumental architecture, including temples dedicated to him. The Pyramid Texts, dating to this period, reference Horus extensively, indicating his esteemed status in funerary practices and royal ideology ("Who's who in ancient Egypt", 2000). He was associated with resurrection and played a critical role in the mythological narratives surrounding the afterlife, particularly in connection with the myth of Osiris (Elias, 2012).

By the Middle Kingdom (circa 2055–1650 BCE), reverence for Horus was further solidified through his integration with other deities, leading to a complex pantheon that included various forms of Horus, which reflected local worship practices (Hafez, 2019). This trend of syncretism continued throughout the New Kingdom as Horus maintained a prominent role in state religion, monitored by numerous temples and shrines dedicated to him across Egypt, such as those in Edfu and Hierakonpolis (Elias, 2012).

During the Intermediate Periods of ancient Egypt, notably the First (circa 2181–2055 BCE) and Second (circa 1630–1540 BCE) Intermediate Periods, the worship of Horus, particularly Heru-Ur (Horus the Elder), evolved in response to shifting political dynamics, regional agricultural practices, and varying religious beliefs across Egypt. This period was marked by increasing fragmentation, decentralization of power, and the emergence of local cults, leading to distinct forms of worship and reverence for deities such as Horus.

Local Cult Centers: During the First Intermediate Period, the political landscape became decentralized, notably amidst the disintegration of unified pharaonic authority. Local centers emerged with significant worship of Heru-Ur, particularly in regions like Edfu and Hierakonpolis. At these sites, temples dedicated to Horus were built, and local cult practices revolved around agricultural cycles and fertility, reflecting Horus's role as a creator and provider of sustenance. This evolution is supported by evidence from archaeological findings that highlight localized religious practices that adapted traditional mythology (Fahim, 2020).

The Role of the Sons of Horus: Another significant aspect of Horus worship during the Intermediate Periods is the veneration of the "Sons of Horus," specifically associated with the mummification and protection of the deceased. Heru-Ur became connected with funerary practices, as his sons—Imsety, Hapy, Duamutef, and Qebehsenuef—were assigned to protect various organs of the deceased during embalming rites, a practice that continued into the Third Intermediate Period and after. This reflects the ongoing influence of Horus in the practices concerning the afterlife, underscoring his importance even when centralized worship began to decline (Badr, 2023).

Artistic Representations and Funerary Practices: The funerary art and objects from this era often depicted Horus or utilized his symbols, showcasing his protective nature. The incorporation of Horus into coffin decorations became prevalent, signifying the divine safeguarding of the deceased's spirit in the afterlife. This association with funerary customs persisted across varying dynasties, indicating Horus’s role as a mediator between earthly existence and the afterlife (Fahim, 2020). During the Second Intermediate Period, particularly under the Hyksos influence, traditional Egyptian ideals melded with Near Eastern customs, yet Horus remained a constant figure representing kingship and divine protection (Stantis et al., 2020).

Cultural Syncretism: As the Hyksos established dominance in northern Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, local devotion to Horus was reframed within the broader cultural context of this foreign rule. While the Hyksos adopted some foreign gods, traditional Egyptian deities like Horus were often integrated into their practices, leading to hybrid forms of worship that included both indigenous and foreign elements. This cultural syncretism underscores the adaptive quality of Egyptian beliefs regarding Horus, promoting his attributes amidst diversity rather than diminishing his importance (Ben-Tor, 2010; Sanni & Phiri, 2024).

Literary and Artistic Evidence: Textual references from tomb inscriptions and relics indicate that the narratives surrounding Heru-Ur remained integral to local belief systems, centering on themes such as protection, fertility, and rightful kingship. These narratives were critical for legitimizing rulers during these fragmented times, affirming Horus's role in maintaining order (Elsayed, 2023). Artistic representations grew more localized in style and iconography but often retained essential elements that depicted Horus’s valor and protective qualities.

In summary, during the Intermediate Periods, the worship of Horus manifested in multifaceted ways, adapting to sociopolitical shifts and regional differences across ancient Egypt. The emergence of local cult centers, the integration of the Sons of Horus into funerary practices, and adaptation to new cultural contexts all reflect Horus's enduring significance as a deity associated with kingship, protection, and resurrection—even amidst the turbulence and fragmentation characteristic of these periods.

The worship of Horus evolved significantly from the Middle Kingdom to the New Kingdom, reflecting changes in political structure, religious practices, and social dynamics within ancient Egyptian society.

Centralization of Worship and Political Context: During the Middle Kingdom (approximately 2055–1650 BCE), the political landscape stabilized after the tumultuous Intermediate Periods. Horus was primarily acknowledged in a political capacity, but it was the metaphorical connection between the pharaohs and Horus was essential to state ideology. In the New Kingdom (approximately 1550–1070 BCE), this connection intensified, with pharaohs increasingly equating themselves with Horus to solidify their authority. The adoption of titles that incorporated Horus (e.g. "son of Horus") became commonplace, reinforcing the idea that the pharaoh embodied Horus on Earth (Judd 2004).

Temple Construction and Institutionalization of Cults: The New Kingdom saw the construction of temples dedicated to Horus, notably the Temple of Edfu, which celebrated Horus’s mythological battles against Seth and themes of resurrection and kingship. While local cults existed during the Middle Kingdom, their scale and prominence were less compared to those in the New Kingdom, where the temple economy and priesthood became more organized and influential within society. These temples served as economic and religious centers, demonstrating Horus's elevated status as a deity who provided protection and prosperity to the state and its people (ReFaey et al. 2019; Megahed 2020).

Integration with Other Deities: In the New Kingdom, Horus underwent syncretism with other significant deities such as Re, resulting in the emergence of composite forms like Re-Horakhty which means "Ra, who is Horus of the two horizons". These intertwined the solar aspects of Re with the protective roles of Horus. This integration enhanced Horus's status and expanded worship practices to reflect broader cosmological beliefs (Porceddu et al. 2018). Comparatively, during the Middle Kingdom, while some syncretism occurred, local cult practices around Horus remained pronounced, primarily focusing on his role in kingship and conflict (Judd 2004).

Funerary Practices and Afterlife Beliefs: In both the Middle and New Kingdoms, Horus played a crucial role in funerary rites, symbolizing resurrection and the protection of the deceased. However, during the New Kingdom, the emphasis on Horus's protective qualities aligned more closely with royal ideology and the deification of pharaohs in the afterlife. This period saw an evolution in mythological narratives, with Horus prominently featured in funerary texts and tomb art, symbolizing the hope for resurrection and reinforcing the pharaoh's divine status (ReFaey et al., 2019). The "Book of the Dead" also became increasingly significant, incorporating themes and symbols related to Horus, thus influencing personal religious practices among the elite (Porceddu et al., 2018).

Symbolism and Amulet Use: The Eye of Horus, a symbol for protection, health, and restoration, gained immense popularity during the New Kingdom and became ubiquitous in amulet form. It served as a personal protective charm for the living and became intricately linked to funerary practices. This shift reflects how the worship of Horus transitioned from primarily state-driven to more personal and widespread veneration, emphasizing individual protection throughout the New Kingdom (ReFaey et al., 2019).

Regional Variations and Local Practices: Throughout both periods, regional variations in the worship of Horus persisted. However, during the New Kingdom, there was a pronounced effort to standardize worship through the establishment of a comprehensive priesthood and temple network. Local practices, while still important, began to align more closely with the increasingly formalized narratives and rituals prescribed by central temple institutions (Judd, 2004).

During the Ptolemaic period (332–30 BCE), the worship of Horus transformed within a Hellenistic context while his significance largely remained intact in Egyptian religion. The Ptolemies utilized Horus to legitimize their ruling status by incorporating him into their identity as pharaohs ("undefined", 2011). This era marked a peak in artistic representation and textual references to Horus, expanding his symbolism into broader religious iconography and impacting rituals, administrative policies, and creative expressions in the arts (Gasparro, 2018).

Edfu was a settlement and cemetery site from around 3000 BC onward. It was the 'home' and cult centre of the falcon god Horus of Behdet (the ancient name for Edfu), although the Temple of Horus as it exists today is Ptolemaic. Started by Ptolemy III (246–221 BC) on 23 August 237 BC, on the site of an earlier and smaller New Kingdom structure, the sandstone temple was completed some 180 years later by Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos, Cleopatra VII’s father. This Ptolemaic temple, built between 237 and 57 BC, is one of the best-preserved ancient monuments in Egypt. Preserved by desert sand, which filled the place after the pagan cult was banned, the temple is dedicated to Horus, the avenging son of Isis and Osiris. With its roof intact, it is also one of the most atmospheric of ancient buildings.

Moreover, the localization of Horus worship varied across Egypt, with different regions celebrating him in diverse forms. In Akhmim, for instance, Horus was linked with the fertility god Min, illustrating how local traditions and deities blended with the overarching narratives (Elias, 2012). Temples dedicated to Horus were common across various cities, further illustrating the widespread worship of this deity throughout different historical epochs (Hafez, 2019).

In examining the significance of Heru-Ur (Horus the Elder) and Re (Ra, the sun god) within ancient Egyptian religion, it is essential to consider their differing roles and the extent of their worship throughout Egyptian history. Both deities held significant places in the pantheon, but they served distinct purposes and were revered in different contexts.

Re, the sun god, was among the most important and widely worshipped deities in ancient Egypt, often considered the king of the gods. His influence permeated many societal aspects, as he was associated with creation, the sky, and the sustenance of life. The worship of Re can be traced back to the early dynastic period, with numerous temples dedicated to him, most notably the Temple of the Sun in Heliopolis, which served as a central cultic site. This temple played a vital role in the religious practices of ancient Egypt, as it was believed that Pharaohs would unite the dual kingdoms of Egypt during important rituals dedicated to Re Dong et al. (2015)(ZANINI et al., 2024; . Re was also extremely important in the pharaonic ideology, viewed as the protector of the pharaoh and a symbol of divine kingship. His identification with the daily cycle of the sun reinforced concepts of resurrection and renewal, fundamental tenets in the Egyptian belief system (Chan et al., 2015; .

In contrast, Heru-Ur, while also significant, primarily emerged as a protector god and a symbol of kingship through his connection to the pharaohs. Worship centers for Heru-Ur, such as the Temple of Edfu, were indeed substantial but often did not reach the same levels of national prominence as those dedicated to Re. Heru-Ur represented particular aspects of kingship, embodying the rightful rule and protection of the nation; however, his narratives were often centered around mythological tales, like those of his battles against Seth for the kingship of Egypt, which served as metaphors for the struggle between order and chaos in a changing political landscape Ostende et al., 2022).

Throughout different periods of Egyptian history, Re consistently represented the overarching, unifying force within the pantheon, whereas Heru-Ur's significance, while integral, was more localized and often concerned with succession and protection of the ruling king specifically. During the New Kingdom, Re's worship culminated in the Solar Theology movement, which solidified his status as preeminent over other deities. Pharaohs, especially from the 18th Dynasty onwards, emphasized their connection to Re through royal names and monumental inscriptions, which often illustrated their divine right to rule in tandem with Re's blessings (ZANINI et al., 2024; (Chan et al., 2015; .

Moreover, Re's narratives often intertwined with those of other major gods, including Osiris and Isis, whereas Heru-Ur's stories were frequently portrayed independently, focusing more on his protective qualities rather than the creation and cycling themes echoing throughout Re's mythos (Chan et al., 2015; Ostende et al., 2022). This divergence highlights why Re retained a more broadly recognized and worshipped status across a wider geographical area and demographic over time.

Heru-Ur was undoubtedly important, especially in the context of specific local cults and the symbolism intertwined with pharaohs' divine right to rule. However, when comparing the two, it becomes apparent that Re was more integral to the fabric of Egyptian theology as a whole and attracted a broader worship base across different regions and periods in ancient Egypt. His embodiment of the sun and central role in creation positioned him as a cornerstone of the theological and socio-political identity of ancient Egyptians.

In conclusion, while both Heru-Ur and Re played significant roles in Egyptian mythology and religion, Re's position as the sun god placed him at the pinnacle of worship in terms of impact, breadth of reverence, and theological importance throughout ancient Egyptian history.

Places

Heru-Ur was widely worshipped in ancient Egypt at several key centers and temples throughout the country, playing a pivotal role in the religious and cultural life of the Egyptians. His primary cult centers varied over different periods of Egyptian history, reflecting the evolution of worship related to this important deity.

One of the most significant temples dedicated to Heru-Ur is located in Edfu, in Upper Egypt. The Temple of Edfu, constructed during the Ptolemaic period (approximately 237-57 BCE), is one of the largest and best-preserved temples in Egypt, specifically dedicated to the falcon-headed god Horus. Extensive inscriptions covering the walls narrate the mythology associated with him, including his battles against Seth. The temple complex served as a major center of worship, contributing broadly to the local and national devotion of Horus during and beyond the Ptolemaic period (Megahed, 2020).

Another notable center of worship for Heru-Ur was located in the city of Hierakonpolis, one of the oldest and most important urban centers during the Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods. Archaeological findings in Hierakonpolis, including significant votive objects and reliefs, indicate that the worship of Horus had deep roots tied to early kingship and the establishment of divine rule. This location plays a crucial role in the political and religious narrative surrounding the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, positioning Heru-Ur as a central figure of power and legitimacy (ReFaey et al., 2019).

Additional evidence of Heru-Ur's worship can be found in regions such as Heliopolis, where temple complexes celebrating solar deities, including aspects of Horus, were prevalent. Heliopolis served as a vital religious hub associated with various divine figures connected to the sun and creation, further illustrating the localized forms of Horus worship (ReFaey et al., 2019).

Over different eras, the reverence for Heru-Ur expanded and adapted. For instance, during the Middle Kingdom, texts and artifacts increasingly depicted Heru-Ur alongside Osiris, reflecting the syncretism and evolving beliefs surrounding themes of resurrection. This adaptation allowed for a broader interpretation of Heru-Ur's role, encompassing protection, kingship, and the afterlife (Katat, 2015).

Moreover, the presence of Heru-Ur in significant cities such as Memphis and Thebes cannot be overlooked, as both served as major political and religious centers during various epochs of Egyptian history. The temples dedicated to various aspects of Horus in these locations contributed to the proliferation of his worship (Megahed, 2020).

Overall, the worship of Heru-Ur throughout Egyptian history reflects a dynamic adaptation of religious practices. His presence at key shrines in Edfu, Hierakonpolis, Heliopolis, Memphis, and Thebes underscores his importance as a principal deity, embodying kingship, protection, and the struggle against chaos throughout ancient Egyptian civilization.

The Stories

The mythology of Heru-Ur (Horus the Elder) encompasses several stories that illustrate his attributes, significance, and the vital role he played in the ancient Egyptian pantheon. Below is a list of mythological stories associated with Heru-Ur:

The Myth of the Eye of Horus: One of the most renowned stories involves the Eye of Horus, which is said to have been wounded or gouged out during a battle with Seth. This story symbolizes both healing and protection, as Thoth restored the eye, representing regeneration. The Eye of Horus then became a potent symbol in ancient Egypt, associated with well-being and prosperity (ReFaey et al., 2019)MacDonald et al., 2018).

The Battle Against Seth: Heru-Ur's conflict with Seth is a predominant theme in Egyptian mythology. He engages in a prolonged struggle for kingship and the rightful inheritance of his father, Osiris, after Osiris is murdered by Seth. This narrative showcases the eternal struggle between order (Horus) and chaos (Seth) and also highlights the importance of rightful succession in the divine hierarchy of the ancient Egyptian state (Porceddu et al., 2018; (Romanchuk, 2023).

The Birth and Protection of Horus: Another significant story involves the birth of Horus to Isis and Osiris. Following Osiris's death, Isis fled to hide her son from Seth, who sought to eliminate any threat to his rule. This narrative emphasizes the protective aspect of Heru-Ur, as his early life symbolizes resurrection and the potential to restore order to Egypt following chaos and tyranny (Lange‐Athinodorou, 2021).

The Trial of Horus and Seth: The trial is another essential myth where Horus and Seth bring their grievances before the other gods. The outcome of this trial determines the rightful ruler of Egypt and is pivotal for establishing the authority and legitimacy of Horus as the pharaoh's divine patron, reinforcing his role as a protector of both the land and the royal lineage (Romanchuk, 2023).

The Rebirth of Osiris: In connection to Horus, the myth of his father's resurrection is crucial. Osiris, who had been killed by Seth, is brought back to life by Isis, which sets the stage for Horus's quest to avenge his father and reclaim the throne. This narrative embodies themes of death and resurrection integral not only to Horus's story but to broader Egyptian beliefs regarding the afterlife (ReFaey et al., 2019).

Horus as the High Protector of the Pharaoh: This overarching thematic story depicts how the pharaohs identified closely with Horus. They were seen as living embodiments of Horus on Earth, legitimizing their rule through divine association. This association is manifest in the vocabulary of the pharaohs, where titles often invoked Horus’s name, reflecting the belief that the pharaoh's authority stemmed from the god's protective power (Porceddu et al., 2018; Olgun, 2018).

Horus and the Sun: As a sky god often associated with solar connections, another myth relates to his embodiment of the sun, paralleling the deity Re. The iconography and worship of Horus engage with celestial narratives, which enhance his status in mythological contexts that emphasize the cyclical nature of day and life alongside his association with kingship and protection (Zakirova et al., 2023).

Figure 24.

In conclusion, the stories surrounding Heru-Ur are diverse, reflecting his integral character in the mythological landscape of ancient Egypt. His role encompasses themes of protection, succession, order versus chaos, and divine kingship, contributing significantly to the understanding of the Egyptian worldview where gods were interwoven with the political and social fabric of their civilization.

STARGATE

Her-ur only shows up in three episodes, Thor's Chariot," "Secrets," and "The Serpent's Venom".

Figure 25. Heru-ur played by Douglas Arthur (Stargate SG1 1998).

Background information

For thousands of years, Heru'ur, under the name Horus, controlled the planet Tagrea. At some point around 300 years before the present, he abandoned the planet, either due to a lack of resources remaining or a rebellion. Whatever the reason, the people buried the Stargate and destroyed all traces of that part of their history where Heru'ur ruled. Only a small sect knew the truth about Tagrea's past with Heru'ur and still worshiped him as a god, collecting artifacts from his time as ruler of that planet. (SG1: "Memento")

1998

Figure 26. Heru'ur with his helmet/mask up.

After the death of his father, Ra, Heru'ur took control of most of his empire, and became one of the dominant System Lords. Eventually, taking advantage of the fact that Thor's Hammer was destroyed, Heru'ur attempted to conquer Cimmeria despite it being a planet protected by the Asgard. The Cimmerians contacted Earth who sent SG-1 to help. After a brief encounter with Heru'ur himself, Captain Samantha Carter and Doctor Daniel Jackson were able to use the Hall of Thor's Might to contact Thor himself. Thor came in his ship and destroyed Heru'ur's troops, camp and ship landing platforms. With no other option, Heru'ur retreated through the Stargate rather than be taken. (SG1: "Thor's Chariot")

Figure 27. Heru'ur's symbol.

For a long time, Heru'ur was a rival of Apophis. When he learned Apophis and Amaunet had sired a Harcesis child, Heru'ur attempted to take the child. However, Teal'c and Dr. Daniel Jackson were able to deceive him into thinking Apophis had the child, while manipulating Apophis and Amaunet into believing Heru'ur had stolen the child. Heru'ur nearly killed Daniel Jackson, but was forced to retreat when Colonel Jack O'Neill damaged his hand device by throwing a knife through it (and Heru'ur's hand). (SG1: "Secrets")

For generations, Heru'ur controlled the planet Juna though this was mainly through his Jaffa as he hadn't actually visited in a long time. At some point before his death in 2000, SG-1 arrived and informed the people they no longer had to worship Heru'ur. After winning a rebellion against Heru'ur's Jaffa, they instructed them to bury their Stargate. This kept Heru'ur or any other Goa'uld from returning until Cronus reclaimed the planet in his ship. (SG1: "Double Jeopardy")

1999

When Sokar returned, he made his presence known by attacking the forces of Heru'ur. (SG1: "Serpent's Song")

Following the fall of Apophis, Amaunet entered the service of Heru'ur. Amaunet somehow learned the truth of what happened to her son, and led an invasion force to Abydos, taking many Abydonians hostage and regaining her son, capturing the Abydonians as a pretext to trick Heru'ur. Concerned the System Lords would keep looking for him, Amaunet entrusted him to one of her handmaidens, who took him to sanctuary on Kheb. (SG1: "Forever in a Day")

2000

Heru'ur sent a force consisting of several motherships after Klorel in order to capture him. Klorel piloted his ship towards Tollana as he knew that the Tollan would use their ion cannons against them. Two of Heru'ur's motherships were destroyed in the process but Heru'ur himself survived. (SG1: "Pretense")

Eventually, Heru'ur sought out Apophis to forge an alliance for control the Goa'uld Empire. As a sign of friendship, Heru'ur offered Apophis Teal'c, who had been captured by Heru'ur's Jaffa. SG-1 and Jacob Carter sabotaged the alliance hoping it would result in a war that would decimate both System Lords' forces. However, Apophis had brought a cloaked fleet into the minefield and used it to protect himself as he destroyed Heru'ur's Ha'tak, killing him. Apophis easily absorbed Heru'ur's forces into his own becoming the most powerful System Lord in existence. Teal'c managed to escape on a Death Glider with the help of Rak'nor, the Jaffa who had originally kidnapped him for Heru'ur. (SG1: "The Serpent's Venom")

Months later, the System Lords fell into disarray with the deaths of Heru'ur, Apophis and Cronus, the most powerful remaining System Lords. The System Lords held a summit to reconcile the power vacuum left in the wake amongst the remaining System Lords. It was not to be. Heru'ur's death as well as those of Apophis and Cronus helped pave the way for the return of Anubis. (SG1: "Summit", "Last Stand")

Personality

Unlike the other System Lords, Heru'ur personally led his troops into battle, fighting on the front lines alongside them. While just as arrogant and ruthless as the rest of his kind, Heru'ur greatly respects the Jaffa who served under him, feeling a sense of warrior kinship among them and treating them more like comrades in arms rather than cannon fodder, furthering their loyalty to him. However, Heru'ur was known for being merciless toward his enemies as he was willing to viciously torture and interrogate his prisoners unless they conceded to his demands.

Identity: Gerak mentioned that Karrok was First Prime of Horus. It is possible that Heru'ur and Horus are one and the same (Heru'ur means "Horus the Elder"). Also, the Tagrean Tarek Solamon referred to Heru'ur as Horus after he abandoned Tagrea. Teal'c confirmed that this was Heru'ur, recognizing the symbol of Horus as being that of Heru'ur. Interestingly, he is one of only two Goa'uld who wore golden Jaffa armor and actively entered combat alongside his troops, the other being his nemesis (and paternal uncle) Apophis. (SG1: "Memento", "Origin")

References:

(2000). Who's who in ancient egypt. Choice Reviews Online, 37(09), 37-4868-37-4868. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.37-4868

(2011). Untitled. Euscorpius, 2011(119). https://doi.org/10.18590/issn.1536-9307/2011v.2011.issue119

Chan, Y., Fisher, P., Tilki, D., & Evans, C. (2015). Urethral recurrence after cystectomy: current preventative measures, diagnosis and management. British Journal of Urology, 117(4), 563-569. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.13370.

Cline, Eric & David O'Connor (editors), Thutmose III: A New Biography, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2006. p.415

Dong, D., Jackson, T., Wang, Y., & Chen, H. (2015). Spontaneous regional brain activity links restrained eating to later weight gain among young women. Biological Psychology, 109, 176-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.05.003

Editors of History.com. (2018, January 4). The Sphinx. History.com. https://www.history.com/articles/the-sphinx#:~:text=Inscriptions%20on%20a%20pink%20granite,the%20power%20of%20the%20sun.

Elias, J. (2012). Akhmim.. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah15024

Elsayed, M. (2019). Lion as an epithet of horus of behdety at edfu. Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies, 9(2), 207-218. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejars.2019.66991

Gasparro, G. (2018). Anubis in the “isiac family” in the hellenistic and roman world. Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 58(1-4), 529-548. https://doi.org/10.1556/068.2018.58.1-4.31

Hafez, S. (2019). Hormerty on some portable monuments. Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality, 16(1), 31-38. https://doi.org/10.21608/jaauth.2019.56893

Hany, N. and elweshahy, m. (2018). Horus, the son of osiris. Minia Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research MJTHR, 3(1), 276-315. https://doi.org/10.21608/mjthr.2018.253146

Katat, S. (2015). The iconography and function of winged gods in egypt during the græco-roman period. المجلة العلمية لکلية السياحة و الفنادق جامعة الأسکندرية, 12(12), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.21608/thalexu.2015.45255

Lange‐Athinodorou, E. (2021). Implications of geoarchaeological investigations for the contextualization of sacred landscapes in the nile delta. E&g Quaternary Science Journal, 70(1), 73-82. https://doi.org/10.5194/egqsj-70-73-2021

Lehner, M. (1992). Reconstructing the Sphinx. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 2(1), 3-26.

MacDonald, L., Nocerino, E., Robson, S., & Hess, M. (2018). 3d reconstruction in an illumination dome.. https://doi.org/10.14236/ewic/eva2018.4

Megahed, H. (2020). Hydrological and archaeological studies to detect the deterioration of edfu temple in upper egypt due to environmental changes during the last five decades. Sn Applied Sciences, 2(12). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-03560-x

Meltzer, Edmund S. (2002). Horus. In D. B. Redford (Ed.), The ancient gods speak: A guide to Egyptian religion (pp. 164). New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

Olgun, H. (2018). Hz. musa’nın yüzleştiği statüko: kadim mısır’ın ma’at doktrini. Mi̇lel Ve Ni̇hal Inanç Kültür Ve Mitoloji Araştırmaları Dergisi, 15(2), 149-169. https://doi.org/10.17131/milel.505037

Ostende, M., Schwarz, U., Gawrilow, C., Kaup, B., & Svaldi, J. (2022). Practice makes perfect: restrained eaters’ heightened control for food images.. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/prjh3

Piankoff, A. (1932). Two Reliefs in the Louvre Representing the Gizah Sphinx. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 18(1), 155-158.

Porceddu, S., Jetsu, L., Markkanen, T., Lyytinen, J., Kajatkari, P., Lehtinen, J., … & Toivari-Viitala, J. (2018). Algol as horus in the cairo calendar: the possible means and the motives of the observations. Open Astronomy, 27(1), 232-263. https://doi.org/10.1515/astro-2018-0033

Porceddu, S., Jetsu, L., Markkanen, T., Lyytinen, J., Kajatkari, P., Lehtinen, J., … & Toivari-Viitala, J. (2018). Algol as horus in the cairo calendar: the possible means and the motives of the observations. Open Astronomy, 27(1), 232-263. https://doi.org/10.1515/astro-2018-0033

ReFaey, K., Quinones, G., Clifton, W., Tripathi, S., & Quiñones‐Hinojosa, A. (2019). The eye of horus: the connection between art, medicine, and mythology in ancient egypt. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4731

ReFaey, K., Quinones, G., Clifton, W., Tripathi, S., & Quiñones‐Hinojosa, A. (2019). The eye of horus: the connection between art, medicine, and mythology in ancient egypt. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4731

ReFaey, K., Quinones, G., Clifton, W., Tripathi, S., & Quiñones‐Hinojosa, A. (2019). The eye of horus: the connection between art, medicine, and mythology in ancient egypt. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4731

Romanchuk, A. (2023). “the dispute between horus and seth” and the emergence of the early kingdom of ancient egypt. Journal of Ethnology and Culturology, 33, 69-79. https://doi.org/10.52603/rec.2023.33.08

Sheposh, R. (2024). Great Sphinx of Giza | EBSCO. EBSCO Information Services, Inc. | www.ebsco.com. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/anthropology/great-sphinx-giza#:~:text=Because%20limestone%20is%20a%20relatively,Egyptian%20Supreme%20Council%20of%20Antiquities.

ZANINI, M., Folland, J., & Blagrove, R. (2024). Durability of running economy: differences between quantification methods and performance status in male runners. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 56(11), 2230-2240. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000003499

Zakirova, A., Maigeldiyeva, S., & Tuyakbayev, G. (2023). Linguacultural and cognitive aspects of teaching the language of kazakh legends. Citizenship Social and Economics Education, 22(3), 137-151. https://doi.org/10.1177/14788047231221109