Thesis Chapter 2: Literature Analysis; Finding the Tools

Human thought and customs are similar enough in the course of development around the world that they are able to be compared in a historical sense. This is not to say that world cultures are the same as each other or that all peoples go through the same mythic ‘checklist’ or that variations in cultures around the world aren’t important or valid. It merely suggests that humans tend to make analogous connections, especially to death and the afterlife. Pearson states that because “most ancient funerary rites seem to be archaeologically invisible, … the act of burial provides – a wide variety of potential information about past funerary practices and their social contexts” (Pearson, 1999). These aspects of their culture then lend archaeologists possible explanations as to why artifacts may be discovered with the deceased.

In this chapter I’ll be examining, in overview, various examples of burial rituals and grave goods from around the globe. Initially I will be showing the general nature of burials in their well-known examples and with each following case study I will be increasing the focus onto the cultural groups of Neolithic New Zealand. First, by showing a general grave good case study I will provide readers the background to what will soon become more specific. The level of technology and the material culture, though, will be less ‘advanced’ than the initial example of King Tutankhamun of Egypt during the Bronze Age. Then I will show, moving from Western Europe toward Eastern Polynesia, that rituals based on commonalities of the human condition allow us to respectfully hypothesize as to why tools, such as the Polynesian toki, have been found as grave goods. Based on studying other archaeologists’ research, reasoning suggests that with cultural and technological advancements comes not only a surplus of useful tools of which can become status symbols because of the cost of production, craft specialization, trade, and rarity variables, but also an importance to display the fact that something that came from the earth could be used to control it, which made the people grander than the wild surrounding the community. The reason that this tracks as a logical idea is because while tools, like adzes, may not have been too difficult to create, the idea of creating them was powerful because it was representative of a person being able to control the world around them. Someone had the idea that if they shaped a rock in the proper way, they could use it to carve meat off bone, or to carve away at trees and carve up the soil to use for planting. This takes a level of forethought that human beings find extremely important and valuable, and the adze is a physical representation of this foresight of which the deceased’s families wished to boast.

There are several viewpoints about burial rites from which opinions can be draw. According to Van Gennep, there is a universal theory of rites of passage and burial is one of the postliminal rites, in order to enter the dead into a “new world” (Van Gennep, 1960 in Pearson, 1999). I draw heavily upon the idea that there is a theory that every culture has some sort of rites of passage and that a great many of them have death, in particular, in mind. While burials and funerals have been approached with varying emotions and some superstitions, for example the idea of creating a vampire within a Greek Orthodox Christian culture if anything is crossed over the body before burial (Avdikos, 2013), they continuously link back to that people's’ worldview. “[W]orldview is a web of cultural meanings… a fundamental factor and context in constructing an identity… a set of rules that organizes daily life and a mechanism for comprehending the relationship between human beings” (Avdikos, 2013) and, therefore, a religion upon which a culture bases its rites and rituals around, is a worldview. One reaction of which does seem to be in every worldview is a fear of the dead or of becoming dead, because it is a state of being over which we have no control. As Pearson claims, “fear and veneration may go hand in hand” (Pearson, 1999: 25) and thus separation of ourselves from them and attempting to praise them, whether in memory or gifts, could be ways in which that fear is controlled in the mind of the living.

In the cases of archaeological burial goods, we cannot only find manipulation of the body and its’ positioning, but the grave goods also relay personal and societal information. With what was the person possibly connected to? To whom were they important? And should they be remembered? These are some of the questions that post-processual archaeology attempts to answer.

Grave Goods

Artifacts found along with the body of a person are commonly known as grave goods. Anything can fit into this definition: food, clothes, weapons, tools, makeup, accessories, art, symbols, pets, and human sacrifice. Archaeologists have, therefore, subdivided the category into two with the most obvious distinction, whether the material culture is found on the body (clothing or jewelry) or accompanying it (pottery or weapons) although these specifications will overlap in many cases (Ekengren, 2013). Often thought to be tied with the life of the person the artifact was buried with, archaeologists have long attempted to decipher the purpose behind the decisions made by the people left behind to bury useful objects in graves. As some scholars point out, “the dead do not bury themselves” the appearance of the lives of the deceased are swayed by the people who bury them and therefore, according to Härke, “[T]hese images (or in other words: the ideal world) may coincide with the real world - but then again, they might not” (Härke, 1994: 32).

As part of post-processional archaeological research, this critique must be taken into account while developing the hypotheses as to the possible symbolic nature of material culture. Whether or not the material found is a true description of a person’s life is less important in general to the significance of having artifacts be present within a grave. Especially if the location was secret or respected enough for grave robbers to have not interceded at any time because they want or need the goods more than the deceased which leaves archaeologists with something to study. The people who are taking the acting role of burying the bodies found are showing us that, even putting the symbology aside, they found a purpose for actively, and with forethought, leaving potentially useful artifacts with one who would never use them again, at least not on this plane of existence.

Development of an afterlife is often reasoned to be the reason for burial artifacts as part of the process of the rituals tell the living that the dead will need whatever is buried with them. Death and the subsequent funeral, as the final ritually transformative processes, are both meaningful for the social dynamics of the dead and those left alive. The living are demonstrating the social and personal: ideological, emotional, and physical changes that go along with dealing with death (Ekengren, 2013). From one standpoint, the artifacts are more than just objects and have a symbolic meaning, which we should be able to reason out with enough data. With each piece of material culture, the world in which the person lived becomes clearer if the pieces are meaningful representations of aspects of that person’s life. I briefly brought up the ancient Egyptian king Tutankhamun; since Howard Carter discovered his tomb in the early 1920s, archaeologists have been attempting to recreate a picture of the nineteen-year-old, boy-king’s life. This is relevant because even though King Tutankhamun was young, his is one of the richest tombs ever discovered with over five artifacts entombed with him (Williams, 2015). Tutankhamun had not had time to rule the kingdom on his own, becoming the ‘ruler’ at the age of nine with his mother and uncles to rule alongside him until he came of age (Williams, 2015). Like many kings and pharaohs of the time, having extravagantly golden-gilded gifts surrounding a tomb was an easily identifiable sign of wealth and power. As, however, Jon Manchip White suggests in the foreword he wrote for a re-released edition of Howard Carter’s journal on Tutankhamun, "[T]he pharaoh who in life was one of the least esteemed of Egypt's Pharaohs has become in death the most renowned" (White in Carter, 1977). This nineteen-year-old became well-known because of what was left behind, by people who might have buried all of that material in order for the entire reign to be forgotten by future generations. Whether or not these artifacts were a bestowal to honor the dead or a way of simply ridding themselves of memories, there was some sort of purpose to not melting the metal down to re-use or breaking the objects apart. Depending on what was easier to create and what material was easier to find greatly depended on wealth and trade access. It would be no surprise that a king could much more easily have his artisans get a hold of whatever he wanted, and the accessibility to more advanced technology made it quicker and easier to produce whatever they may have needed, both during and after Tutankhamun was alive.

Burials and artifacts older than Egypt’s 18th dynasty of the Late New Kingdom, which is classified as a bronze-age civilization, are found in Neolithic sites (Ramsey, 2010). In this era much of the simplification of manufacturing techniques had not yet come into being. There was no metal work being accomplished, which made manufacturing the stone that much more difficult. Items need a certain amount of time and energy to create, which is what is called the production cost, and during the era known as the Neolithic this would have been greater than during the Bronze Age. To examine this era of history (or prehistory) more specifically, I will be drawing upon a few different cultures around the world whose similarities could start, and end, with the fact that they used stone tools during this time against opposing outside influences.

Neolithic Technology and its Influence on Burials

The Neolithic was a period when there was an increase of stationary, agricultural cultures rather than the roaming bands of hunter-gatherer Paleolithic groups, thus it also saw the rise of common burial mounds and cemeteries (Lenneis, 2007). Kuijt views these mortuary practices “as a form of human behavior that is actively chosen by actors in relation to specific beliefs and a broader worldview and symbolic themes, rather than a direct reflection of social organization” (Kujit, 1996: 315). Based on the rituals interpreted from the Natufian culture within the Levant region, Kujit theorized the cohesion of burial practices and the placement of artifacts in graves reflected the societies growth into an active community (Kujit, 1996). Because it is an act of a social preformative narrative for the invited audience in particular, the symbology of the burial itself and the material within is not necessarily a direct reflection of the deceased’s identity. It is a show, whether for status, authority, or importance, but the central social ethos of the combination of what the community finds most valuable and the ties between “households”, including economically, socially, and religiously (Kuijt, 1996: 315-316).

With the similar rates of technological advancement and stone tool use, the social aspects of the community had to be continuously maintained. The last act of a burial, or ‘mortuary ritual’, would demonstrate the deceased’s influence, be it economic, social, or both (Kuijt, 1996). When looking at ritual burial through this lens, the usefulness of items buried alongside the body becomes increasingly important to the stabilization of a group of people. While there were not many prestige goods, nor grave goods in general, within the Natufian burials, they did sometimes contain utilitarian objects, such as pins for holding clothing together (Kuijt, 1996: 319). This may not leap out at a reader that this is significant but leaving behind any re-usable item can be an example of this ritual practice. As the ritual itself, while “a cohesive force is based, in part, on the realization that mortuary practice is a form of public action, a social drama designed and conducted by the living, often to elicit community participation” is not the show of a higher status or ‘wealth’ (Kuijt, 1996). So therefore, the act of a mortuary ritual was not indicative of people with greater prosperity. The implied social cohesion of the communities’ involvement in that practice would be for either social identification or luxurious boasting. Examples of these include: having the bodies and skulls in particular positions or items being buried alongside bodies, such as shells, bone and shell beads, or pendants for decoration/adornment (Bar-Yosef, 1986 & Kuijt, 1996).

With humans being in constant competition for who will survive and procreate, the agricultural revolution and community settlements were valuable changes. The people living then, however, still had to compete over the resources that were available. During this time of technological and economic development, the cultures had to continue to advance as well, namely within their allocation of responsibilities. When farming or fishing or hunting or gathering by fewer than the entire population, other members of that society were able to produce an ever-increasing number of new instruments and ideas for how to use them. With the ability to form a centralized society that works together to survive and create increasing organizational skills, a society will soon lead to specialized skills for individuals, giving them a particular role and identity in their group (Renfrew & Bahn, 2008).

Burial Practices, Common Artifacts – what would they keep?

The mortuary or burial rituals were most likely not the most important or obvious way to demonstrate the deceased’s power and status in a community. But with the increasing level of personal identity traits for each person, the community saw them a specific way, and would have wanted to honor that, leading to the leaving of items that they believed to be special to the dead. This must have followed some kind of cultural approval of the belief in some kind of an afterlife and/or in ancestor worship (Kuijt, 1996). The specific artifacts included would vary greatly depending upon what materials were available wherever a particular culture existed and what they would have deemed important. Personal artifacts may relate to either a familial or personal identity, which are commonly featured in human burials, and demonstrates the society’s development of shared activities, whether through ritual or in the construction of public works (Renfrew & Bahn, 2008).

In Neolithic England and Western Europe, sites have been found with individuals in different bodily positions and with various dress, tools, jewelry, and weapons with food and drink being the most common (Pearson, 1999). Though the bodies and artifacts are the physical evidence of these people after they passed, the act of the ritual burial itself is telling about their structure of reality. These goods reflect what the cultures find most important in their world, because these were directly impacting how they interacted with their environment, be it just attempting to survive, how they could control it, or how to place themselves apart from it. The fact that they these started rituals, which then continued over generations doesn’t only provide evidence of prehistoric myths and religion, but of a societal understanding and agreement that certain activities are of greater importance to the community; therefore, these ‘privileged practices’ are hailed as having greater importance (Bell, 1992). These practices may or may not have specifically religious connotations, but because it is only a much more modern Western viewpoint that actively separates the sides, many social functions could be for the benefit of the community structure, economy, and religious ideology (Artelius & Svanberg, 2005).

Specifically examining a cemetery with the artifacts that date from the Middle Neolithic in Borgeby, Scania, a region in the south of Sweden, graves of children were found in a large group with miniature replicas of flint axes (Larsson, 2000 & 2003). With an axe workshop site nearby, this may hold symbolic value shown through the sheer numbers that were buried (Artelius & Svanberg, 2005). Whether meaningfully ‘cult’ or ‘ritual’ in purpose the use of the material demonstrates to archaeologists that these children were born into a privileged position in their society. Their group burial and artifact ‘use’ reflects that even without a long life, the interest in them goes beyond their familial circle towards the possible community they were working towards (Artelius & Svanberg, 2005). These flint axe replicas cross the boundaries of definitions for clothing/adornments vs. grave good or gifts. At times these axes were worn about the neck as personal adornments, yet still held the symbolic value to the community of being actual weapons or tools (Lenneis, 2007).

Scania, as region occupied in early Scandinavia, was one of the places from where the Iron Age Vikings hailed. In the same area as the older child cemeteries in Borgeby, there were also gold and silver workshops in the Iron Age (Brorsson, 1998). As this site’s location has similar artifacts to the Neolithic graves, the Vikings commonly buried small necklaces with hammer and axe shapes as pendants [figure 1 below] and the hammer rings [example shown below in figure 2], while found in the Iron Age burials, these adornments are proof of the continuous settlements of Borgeby. The hammer rings and the pendants of Mjölnir (Thor’s Hammer) threaded upon them are thought to be symbols of protection by Thor, the Norse God of lightning, and either Odin or Freya, with a connection to childbirth (Artelius & Svanburg 2005). When found alongside other grave goods such as ceramics, brooches, faunal remains, etc. and within many burials, no matter the gender, age, or social position, these axes and hammer pendants have less of a personal nature and may be intended for general well-being of the community (Artelius & Svanberg, 2005). Instead of being symbolic of a weapon or of an actual tool, a demonstration of a position during the person's’ life, it works into the more religious standpoint, when there is a ritual meaning to putting the time into working on these figures.

Figure 1. 10th century silver hammer pendant, from Birka grave 750. Housed in the Museum of National Antiquities, Stockholm (Photo ATA, Stockholm). (Fuglesang, 1989: 17)

Focusing back on the Neolithic, the United Kingdom and Ireland have several examples of tools or weapons as grave goods, though evidence shows that they were never used as such. Because the symbology of the burial ritual itself could imply differing ideas of what, if anything, awaits us beyond death, as there are different rites across the globe, the items within could likely have a highly symbolic nature. For instance, there are peoples who may bury their dead with blades to cut their ties with the living (Grainger 1998). These blades do not necessarily have to be able to cut, because they will, presumably, not ever be used again, but the mere idea of it being there is what gives it meaning. Another example of this is the nine-thousand-year-old axe that was found in a Mesolithic (Mid-Stone Age) Northern Ireland burial. As the Mesolithic transitions into the Neolithic at the advent of agricultural revolution, the diets, human ways of living, and the societal groupings all dramatically shift in a (relatively) short time span (Jones, 2017). Depending on which cultural area one is referring to, this transition took place at varying dates; however, what is important is to note that because subsistence strategies were so different from what would follow. Because humans did not previously engage in large works and craft specialization as much, it is more impressive that the living would have carved out a fully polished axe that had no sign of use and left it alongside the remains of the dead (Collins & Coyne, 2006). The bones of the cremated body had been identified as male, which could give some of the context behind the artefacts which are suggested to have been buried between c. 7530-7320 BCE (Collins & Coyne 2003: 25, Woodman 2001: 252). This and a few of the other seventeen lithics and two possible microliths found showed possible evidence of burning in the cremation type burial.

Similarly, if we look at sites in Neolithic Britain, c. 4000-2500 BCE, the people also had burials of bodies, both cremated and un-burnt, with grave goods and circular barrows to identify the location of the burial itself. There were also times and places where these markers would also double as boundary lines for land or territory. Whether as a single or a group burial, which according to Thomas does not necessarily mark a differentiation in status, “prestige objects”, such as worked stones and in the late Neolithic copper and bronze pieces, had been found as well. Thomas also suggests that the act of presenting these items to the dead were making the goods symbolic, at the same time heightening the elites’ legitimacy. If a person was buried in a group with their own prestige goods, it had the symbolic meaning of being more important within a larger group (Thomas 2000: 654).

In some places territorially strategic burials are more commonplace. On the island of Gotland off the coast of Sweden, for example, there are still single and multiple bodies burials and grave goods are abundant. In the study done on Pitted Ware Culture (c. 3400-2300 BCE) burial sites in Ajvide, Västerbjers, Visby, Ire, and Fridtorp, the grave goods from 126 adult graves were found and measured along with the goods from 50 children’s graves. When compared across the island there were, according to Molnar, ten items that were the most commonly found: two different types of beads, boars’ tusks, teeth arrangements, axes, edge blades, awls, fish hooks, harpoons, and arrowheads without, at least in terms of the axe tools, there being any specific overall gender bias (Molnar 2010: 9). The higher ratio of more grave goods in gender, in general terms, went to females and in age, to the young (Molnar, 2010). If we look specifically at the axes and awls, in terms of them as tools and not weapons which can be reused and are in most graves, usually more than once, and with every group equally the conclusion was drawn that the goods themselves aren’t as reflective of the individual person, but of the society as a whole.

This is different than the personal adornments which were more common in the Neolithic burials of Central Europe. While cemeteries themselves are not as commonly found in Neolithic Eastern Europe, LPC (Linear Pottery Culture) age sites contained more individualistic burials. There were some graves with snail shell necklaces and head adornments as well as ochre around the head [figure 3] (Nieszery 1995, Abb. 99, 100), but within a male burial there was an adze found along with the shell adornments wrapping around the body [figure 4] (Lenneis 2007: 130-135).

Figure 3. Burial with adornments (Nieszery, 1995: 99)

Figure 4. Male burial (Nieszery, 1995: 100)

Central Europe

As we move southwards into the region, now part of mainland Spain, archaeologists have readily acknowledged that social inequality is what is being developed through time and is being shown with the increasing differences in burial goods (Vila, Domínguez-Bella, Duarte, López, & Tocino 2015). In the Campo de Hockey necropolis in San Fernando (Cádiz) only a few tombs were found to contain grave goods at all. Most of the human burials were sideways facing, in the fetal position, within a cyst or ‘box’ made from piling slabs of rock on top of each other with possible shells and bone that may be found in the smaller graves for a possible functional or ornamental purpose. But the general rule in this locale is that the goods that would be considered prestigious only appear in the three tombs that are also the most complex (Vila, Domínguez-Bella, Duarte, López, & Tocino 2015: 150). The “prestigious” goods in this area have been defined as jewelry made from amber or single amber beads, variscite and turquoise, green and blue respectively, stone beads, polished axes, and ceramics with ochre, a red pigment like cinnabar (Vila, Domínguez-Bella, Duarte, López, & Tocino 2015: 155-159).

Archaeologists who worked and wrote on this site in the Iberian Peninsula theorize that this necropolis burial pattern, with specific area bases and highly size subjective burials, demonstrate the connections to power which were becoming more prevalent in the stationary villages of Neolithic society. This site in particular is one of the major examples where inheritance is a larger aspect of item and territorial ownership, along with differentiation in gender, as demonstrated by location of their graves within the necropolis and the types of grave goods that are contained inside (Vila, Domínguez-Bella, Duarte, López, & Tocino 2015: 159). The major prestige artifacts like amber, variscite, and turquoise beads and polished axes are only found in the most elaborate and largest burials, with very few of each being found in general.

I will focus on the three highly polished axes, two made of sillimanite, found in the “two most notable tombs (E3 and E11 C15 C14)” and the third from a conglomeration of metamorphic rock (Vijande, 2011: 15). Outside the graves, there was another trench dug, and within a perimeter trench there was another highly polished piece of black rock. The archaeologist who worked on this site had identified this too as an axe, one that had been used and worn down, suggesting that it could have been used to dig the very trench it ended up in, though if so, the question would be ‘why’, but the writers make no suggestions (Vila, Domínguez-Bella, Duarte, López, & Tocino, 2015: 157).

Elsewhere in the Northeastern Iberian Peninsula, specific in the region of Catalonia, there are a wide variety of burial sites due to: the high variability of environments, the climate, terrain, and soil composition. These factors also play into the typology of the burials as will, which vary in size, volume of goods, and the ritualistic characteristics of possible gravestones, bodily position, and possible postmortem movement (Gibaja Bao, 2004: 680). Within three cemeteries [map displayed in figure 5 above]: Sant Pau del Camp – SPC, B∂bila Madurell – BM and Cami de Can Grau – CCG, there were many grave goods found as well inside the often one-person, fetal positioned graves. The majority of these graves, from different regions do contain grave goods, including ceramics, plants, ornaments made of turquoise and shells, and tools made from bone and knapped stone. Examining the lithics at each site showed archaeologists that while SPC and CCG had the majority of their stone tools made from a “mediocre flint” the majority of the stone tools buried in BM cemetery were made using a “high-quality flint” suggesting that the people who were buried in that cemetery had a higher social standing, and could get material from further away, as opposed to the local flint pieces (Gibaja Bao, 2004: 681-682).

The stone tools themselves were mostly flakes, blades, cores, and hammer stones with only the notably polished axes being found in the male burials in B∂bila Madurell. This binary status is not the rule of the area, as there have been female burials found within large graves and with more prestige goods than men, and no marked differentiation within the burials in the Camí de Can Grau, because both men and women worked with stone tools. Commonly, however, the agreement between the archaeologists has been that men are more likely to be buried with items made of material from foreign origins which take the tool shapes of querns, cores, stone points, and the polished axes. Women were shown to be more often buried with blades and flakes and children with cores, points, and microliths, suggesting that while the use of stone tools was not divided by gender or age, the division lies in the particular tasks the people were set to do. Even with the goods found in child burials, some of which had more space and grave goods than adult burials [example shown in figure 6]. This also leads archaeologists to speculate that there is an implied social hierarchy in which wealth and status are related and inherited from the older generations. (Gibaja Bao, 2004).

Figure 6. Two examples of adult burials, one male and one female, from "B∂bila Madurell with abundant grave goods" both including pottery and stone tools (Gibaja Bao, 2004: 683).

Romania contains a cemetery in Cernavodă – Columbia D that contains graves and their subsequent goods from the Hamangia cultural phase, present-day countries of Bulgaria and Romania (Kogalniceanu, 2015). This culture, whose Neolithic technological level gave the people the means to make highly specialized artwork were found in the necropolis of Cernavodă in the 1950s along with numerous examples of stone tools, such as axes, adzes, and chisels, the majority of them highly polished (Slavchev 2004-2005). This particular cemetery has two major areas which had been attributed to either various time periods of burials or the social statuses of the people buried within them, playing into the layout and number of the stone artifacts as well (Kogalniceanu 2015: 54).

If we specifically focus on the stone tools found alongside the bodies, there are three different types between which the pieces were separated. To differentiate the types, the archaeologists measured all the tools and compared them with morphological characteristics that will be covered more in Chapter 4. For our purposes at the moment I will be focusing on the action of the people choosing to create these specific ‘tools’ that were likely used as such. While the data from the initial recording of the tools, recorded by Berciu in 1966, suggested that they did not have signs of use-wear done by the tool working, when revisited in the 1970s small chips were recorded on the blade showing its use pre-burial [figure 7] (Kogalniceanu 2015: 53). Other pieces had evidence of reshaping pre-burial that would suggest the reworkability of the tools; pointing to the question of why they would be buried now, especially if they could have continued to prove functionally useful.

Figure 7. Examples of chips on the edge of blades demonstrating the reworking of A) small to medium axe and B) small adze (Kogalniceanu 2015: 52).

Along with the fully finished artifacts, archaeologists also found a small number of fragmented tools (four) and ‘dummy axes’ (eleven identified) that were only used as grave goods. The unfinished pieces and smaller pebble versions are made to resemble the finished product [figure 8] (Kogalniceanu 2015: 53-54). These artifacts follow more closely the representational path which both the Scandinavian and Western European cultures both took part in independently of each other.

Figure 8. Dummies. A) Unfinished tool B) Imitation axe pebble C) Pebble shaped to resemble an adze (Kogalniceanu 2015: 49).

The upper portion of the cemetery notably had much more in the way of grave goods compared to the lower potion, and the majority of the tools found in all areas were adzes. Another aspect of the grave goods between the areas has been where they are placed in relation to the body. In the Upper section the tools are placed near the head and shoulder, which does not appear in the Lower; instead they tend to lay the tools upon the body’s chest, with only two examples of this practice being found in the Upper section (Kogalniceanu, 2015: 58-59). Interestingly, there is not a clear dimorphism between male and female grave goods, as they both contain real and dummy axes and adzes, some which were unfinished and others that were pebbles carved to look like the tools. The raw material is also evenly split, finding goods made of limestone in the lower cemetery, and Greenschists and volcanic rocks in the upper cemetery. In this case, the question is whether these were placed as weapons or tools. Carved stone has many uses: axes can be used chop down trees, hunt, and therefore has use as a weapon. While adzes and chisels are predominantly used for agriculture and for carving wood and leather, like axes they could also be used as weapons. From more extensive analysis, however, use-wear markings have been recorded on both the adzes and chisels suggesting that they were used as tools and thus the axes, which were found buried in a similar way, are ascribed the same meaning for both genders equally (Kogalniceanu, 2015).

The total grave good analysis also includes the ‘dummy’: unfinished, imitation, broken, and miniaturized tools. Tsoraki postulates that when tools found in graves are made out of material in which the true tool would not be useful in, such as amber or clay, that it then must have had symbolic connections (Tsoraki, 2011: 241). Behavior like this, including pieces made from small pebbles is reminiscent of the Nordic cultures that I have previously discussed, and the hypothesis is that the stones themselves had meaning to the people, not as a social status symbol, but as a part of their community identity. This idea was put forth in Kogalniceanu paper because while the true tools, of which were buried, had been used and the raw materials were imported, the imitation and miniature pieces were made from local stones that were easy to gather. In this area the imported and polished stones tools buried were either full, intact pieces or the dummies. If any pieces were found as fragments the breaks looked to be unintentional, and likely post-burial, therefore it is also thought that the completeness of the item correlates to its affectivity in its symbolism. However, if we examine miniatures in the same way, they would not match the completeness model because as Kogalniceanu (cited in Tsoraki, 2011) defined miniature tools as too small to be used and therefore would no longer be functional as the original tool it was based on, thus would not fall within the boundaries of ‘true’ symbolism as defined in this area. This still may have some sort of symbolic meaning, as almost every single grave in these cemeteries contained at least one tool, whether real or a ‘dummy’, that was used as an active tool at some point during its life. Given the area the tools were most likely used for agricultural or woodworking, which could have been symbolic of how the ancestors of the people being buried claimed and settled the land, and may need to continue to hold it in the ‘next world’ (Kogalniceanu, 2015: 61-63).

Moving from West to East

Meanwhile, closer to the cultural practices of the variety of the people who lived in Polynesia, the thinking in China is aspiring to focus more on the elites’ control over the subordinates. “[S]ymmetrical reciprocity is a powerful constraint on status differentiation based on wealth concentration” (Seung-Og 1994: 120). This does imply that there must have been an inherent surplus of food and goods, otherwise the elite would have had to work as hard as everyone else in the house or village to feed their people in a more egalitarian society (Kirch 1984, Sahlins 1970, 1972). Through the trading and selling of pigs, and the burial of same – along with other grave goods, in Neolithic North China, Seung-Og made the argument that the pig itself was a symbol of wealth and elitism, because they were so critical within the diets and within their rituals. Like the jade talismans or shell jewelry, the buried pig skulls are being interpreted as prestige goods along with the representational pig figurines, which can also be found. Within the Shandong province, as an example, through the time periods Seung-Og had traced, the Early Dawenkou to the Longshan, whether high or low the wealth consumption of prestige goods was always running parallel to the amount of pig remains (Seung-Og 1994: 131). While these animal bones and pieces were not used for a utilitarian purpose such as a hammer, axe, or adze would, they still would have been the symbolic figures like Scandinavia’s Thor’s Hammer, and the Melanesian carved boar tusks (Seung-Og 1994).

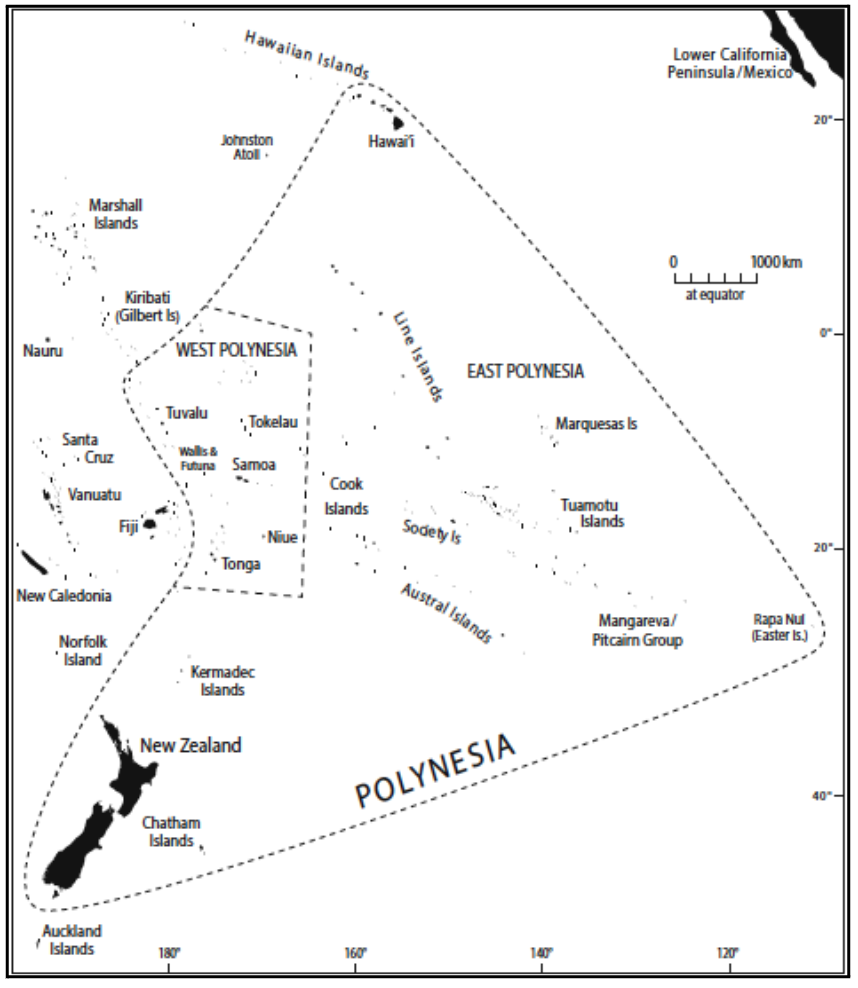

The peoples living in Melanesia seemed to be influenced by the traditions of Neolithic China, based on the finding of pig skulls in what are considered to be prestige burials (Seung-Og, 1994). This Lapita culture, which spread out throughout the Eastern Polynesian islands became influential on the cultures that would follow (Kirch & Green 2001). If we follow the path traced by the Lapita pottery from Southeast Asia through the South Pacific from c. 4000-800 BCE, there can be an argument made for traceable connections through language evolution and material culture (Carson, 2018: 11-15). Looking specifically at the burial goods could grant us another angle of options for the aspect of material culture, because that is what they would have either deemed important enough or easy enough to recreate to leave with the dead. Within these early burials, pottery has often been discovered and used for relative dating, and as discussed in Jim Allen’s paper, Melanesia has had a wider special trade network that grew increasingly complex over time and distance (Allen, 1985: 50-52). With craft specialization, like in the western side of Eurasia island region they would hone their skills, and because of intermediary coastal villages and towns in between larger colonies, goods would be valued and shipped to those who needed them. Even Allen uses the term ‘prestige goods’ for specialty items “such as armshells, shell ornaments, and ceremonial axes” (Allen 1987: 51). Rather than the ‘utilitarian versions’ of the axes, the deciding factor that they were specially made for a ceremonial purpose is what makes the axe prestigious and more valuable, whatever the actual usefulness would have been.

Figure 9. Graph of the spread of people through space and time vs the spatial extent of continuing trade.

In time, following a typical spreading family dynamic, as the societies continue to spread, the contact between them begins to cease (Figure 9) (Allen, 1985: 52). This trend seems to suggest that the earlier and middle era burials would have contained the most distinguished and varied grave goods before the connections withered because the cross-cultural advancement would have continued before the trade slowly ceased causing a differentiation between the groups who would have to learn how to make the goods they used to have shipped over. The people of one such smaller cultural group area in the Massim region scattered in Eastern Papua New Guinea and the islands nearby, are thought to have interacted with of the Lapita People who would have brought their culture, at the latest, around 2900 BP (Shaw 2017: 150) – approx. 2200 years before New Zealand was colonized by Polynesians. Following the Lapita, within the next 700 years, the mixing of ideas in the Massim region created a new sort of pottery design called EPP (Early Papuan Ware), and the carved shells from the island were the most predominantly traded goods (Shaw 2017: 150).

While these prestige goods, pottery and shell ornaments, are said to have altered through time, specialized to whichever island they were made, Shaw makes the point to mention that utilitarian tools had not been recorded as changing over time with geographically regional specificity (Shaw 2017: 150). Using the goods that did change, e.g. pottery and shell design, which were found scattered burial sites across the Massim Region, Shaw compares the designs and radiocarbon date to reconnect the mainland and islands’ trade routes (Shaw 2017: 151). Because shells are still held by the Massim people to be prestige goods, they can symbolically compare to the specially worked tools and tool symbology of the various cultures of whom I discussed earlier in this chapter. Under the idea of symbolic carvings on the shells of various islands beads made from oyster shells called bali made for necklaces were one of the highest valued exchange items and during the Kula exchange period were traded from Rossel Island for pottery as a type of currency, of which the islanders did not have as easily a ready access to (Shaw 2017: 151). Over time these shells may not have only been used as a currency on the island where they were produced, because they are also found within the Rossel Island burials along with other shell material being used as jewelry and decoration or ornamentation.

On islands like this, there is a notable decrease in lithics use as the raw material costs much more to be able to transport and work. With this change of environment, the inhabitants had to continue to adapt their technology, and began making tools, such as grinders, adzes, scrapers, and choppers out of shell (Shaw, 2017: 160-161). According to Shaw, the two adze blade fragments found in Malakai were made from Tridacna and Conus shells in 1330-1290 cal. BP and >310 cal. BP respectively. Although the Conus shell found here was younger than the other it links to the morphology of other shell adzes that were produced over a span of 2000-years possibly starting in the Early Lapita, from 3300 cal. BP (Shaw 2017: 160). Unfortunately, because shells seemingly became a currency in its own right, we can see a drop off in using them as burial goods, even when they are carved to work as tools. This suggests that at that point in time, the goods were too useful to leave in a grave, and depending on the species of shell, that they may have been more difficult to collect and work.

Moving to the Marshall Islands in the Micronesian cultural area, we can once again observe how a constrained environment changes the fashion in which tools and other goods are made. This does create a bias in which we must be aware, because only the wealthiest are receiving burials in general; the probability is higher that the goods found within will be items of prestige, as it would have been easier for them to get more of the raw material. If we focus on the need for farming space on these thin islands with thick centrally located vegetation the burials had to be individualized, and often located near the house, away from working land. Both men and women would have been put through the same burial customs. The chiefs were wrapped in sleeping mats and laid under the grave mound, which would later be leveled off, while commoners were wrapped in mats, weighed down with stones, placed on a raft, and sent to sea (Weisler, 2000). In either case there does not appear to be much in the way of grave goods; some were found to have jewelry: arm rings being the most common, a nose ring, beads, charms, and a pendent, with fewer containing tools: bird bone needles, bone and shell fishhooks, a coral abrader, trolling lures, and one adze tool, made of the Tridacna maxima shell, found within these graves signaling that tools like this were more rare (Spennemann, 1999, Weisler, 2000: 119). This also could be showing that, in terms of the adze, because of the surrounding sea and thus a higher ocean food source, agriculture may not have been as important to be flourishing all over the island and thus would require less work to farm and fewer tools to complete the task. As Weisler relayed, there are few dates for the artifacts that have been found on the Majuro Atoll and the surrounding Marshall Islands; he was, however, able to compare the shell arm rings and trolling lures to others found in Solomon Islands burials, indicating a certain level of trade in between them all (Weisler 2000: 131-133).

As the Roy Mata burial site in Retoka shows, Vanuatu contains nuances from various cultural traditions that reflect in its contemporary and future Pacific Island cultures. Located closer to the culture area of Eastern Polynesia yet still retaining the Lapita cultural traditions, of which keep it tied to the Western side of the Pacific Islands, Vanuatu, has various mortuary sites which date back 3000 years (Valentin 2011). With the Roy Mata burial not having the identifiers of being Lapita makes it more unusual according to Pietrusewsky, because it is noted that “the Lapita-associated remains are often incomplete and poorly preserved, and rarely represent more than a single individual” (Pietrusewsky 1996: 344, Fitzpatrick 2002: 728). The early Lapita burials scattered around Vanuatu, both buried and within caves, were different than the ones further to the West. They had neither a standardized position nor a particular facing cardinal direction for the body, the earliest had no grave goods at all while some later ones had some ornamentation of beads and bracelets made of pig tusk, as in Polynesian tradition, and had either other humans or animals buried alongside the powerful leaders (Garanger 1972, Shutler at al. 2002; Spriggs 1997: 218, Valentin 2011: 61). Only the burials from the early Lapita at Teouma contained decorated pottery as a grave good (Valentin 2010: 217). This lack of any tool kit being found may have been highly influenced by the time and circumstance in which they were buried. Over the 3000 years of Vanuatu mortuary history the Lapita people colonized, standardized, and expanded upon the nearby islands and island chains. While we do not have a full chronology of the islands we know from ethnographic data of the time, “that mortuary ritual had become increasingly an arena for the display of wealth and socio-political power during a period of renewed outside contacts with Fiji and Western Polynesia” (Valentin 2011: 62). Roy Mata’s burial, being a society of Polynesian people, abandoned the use of pottery as grave goods, and included more intact and elaborate grave goods than the older Lapita cemetery sites (Spriggs, 2003: 207-209, Valentin et al., 2011: 49-52, Bedford et al., 2011: 28-34).

Polynesian burial sites

Pietrusewsky continues, “[a]lthough the dates for the Lapita cultural complex fall between 3600 and 2500 years BP, most of the Lapita-associated skeletons are from the terminal phases (c. 2500 years BP) of this cultural complex, while others post-date it” (Pietrusewsky 1996: 344, Fitzpatrick 2002: 728) such as the island chains of Tonga, Samoa, and Fiji, though both Tonga and Samoa are classified as part of Eastern Polynesia and not Melanesia. As part of this cultural group Fiji is right on the boundary between Melanesia and Polynesia and is most often associated with the post-Lapita period. Once the major islands in Western Fiji had been colonized around c. 3000 BP, archaeologists note that it only would have taken around 150 to 300 years to settle on the surrounding islands which still all fall around the time of the Late Lapita with the post-Lapita and early Polynesian traditions beginning a few generations later (Sand & Addison, 2008: 2). This follows the chronology of dispersal of cultural trade mentioned by Allen, because as the people continued to voyage to, and colonize islands further away from their homeland trade and long-distance interaction all but ended (Allen, 1985: 51-52).

Fijian burials and the goods included are a part of the scientific debate of the typological and chronological differences between Post-Lapita or West Lapita and early Polynesian cultural traits, and whether the latter developed straight from the former or in a more diverse conglomeration from the influence of people from many separate areas (Sand & Addison, 2008: 2, Kirch & Green, 2001). While the earliest grave sites on the Eastern Islands of Fiji contained distinctive Lapita pottery, as time progressed towards the Post-Lapita period the pottery decoration became much less intricate and then stopped appearing as grave goods altogether (Kumar et al., 2004). The eastern Fijian island of Moturiki [figures 10 & 11], lying 15 km south of Naigani, is thought to hold the earliest Lapita site based on the evidence of importing and trade of the exotic tempers and early design motifs on the pottery sherds from the Solomon Islands and PNG (Kumar et al., 2004: 16). The major burial to have been discovered in Moturiki was who they would called Mana, a female of over 40 years, from 2600 to 2900 years BP (c. 650 - 950 BCE) placing her in the Lapita Period (Kumar, 2004: 20-21, Clark, 2009). While the end of the Lapita period is marked by the lack of dentate pottery, around 2700 BP, Mana’s burial remains did retain the cultural Lapita burial traditions of some dentate-stamped pottery sherds and shells and bones for possible ornamentation, if not naturally deposited (Nuun, 2017: 99-102).

Mana’s burial is highly distinctive from the Late Lapita sites, dated to approximately 2600 BP, on the main island of Viti Levu only around 12 km offshore. Burials on Viti Levu, in the Sigatoka Sand Dunes, are within a few hundred years of the oldest burial on Moturiki and still contain pottery. These sherds are instead recognized as part of Plainware phase (2600-1600 BP) because they do not have the dentate-stamping or other patterning that typically characterizes the Lapita cultural period (Burley & Dickerson, 2004: 12-13 & Burley, 2005). These practices continue evolving into the ‘proto-Polynesian’ and Eastern Polynesian traditions as what is beyond the Polynesian culture line is crossed and began to include tools and more ornamentation once again (Burley, 2005).

Figure 12. The islands creating the area of the barrier between Remote Oceania and Polynesia “Multilingual map showing the differentiation of Proto-Polynesian language in two subgroups” (Map by Skimel 2017 with work from Pawley 1966, 1967, Biggs 1978).

Tonga and Samoa, as the furthest east islands of Remote Oceania [figure 12], are groupings which have similar linguistics, dating, burial tradition to each other, shown in the artifacts as evidence of trade between the two colonies, and to the late Eastern Fijian sites. They also have evidence of post-Lapita and early Polynesian traditions, via this alteration in the ceramics, but not the changing types of burial goods because “[t]here are no extant Ancestral Polynesian temples or shrines, nor do we have funerary remains that might yield clues to ritual practice” (Kirch & Green, 2001: 237). It is not until the post-Ancestral Polynesian Societies’ burial traditions are practiced that we begin to have well-documented remains and mortuary rituals. The later sites, whether on Tonga or Samoa or Eastern Fiji, often had the similar practices that strongly hint at the elevation of status and chiefdoms as a sign of kingship. Demonstrated through the trading of status and utilitarian goods across the islands and the building of stone lines, earthen or stone mounds, and platform structures for some of the more specially constructed chiefly burials became more widespread around 1000 BP in the middle of a formative phase, which ends up quite different than the rest of Polynesia (Golson 1957 within Green & Davidson 1969, Burley 1998).

Included within the grouping of traded goods are specifically shaped adzes. Both Samoan and Tongan adzes have their own characteristics and appear on their own islands alongside the artifact record in the time of Post-Lapita and Polynesian plain ware ceramics (2650-1550 BP), which already suggests a regional and temporal diversification from Fiji, but also suggests more adaptation to specific functional needs on each particular island before becoming later generalized across multiple colonized islands (Green & Davidson, 1969 & Burley, 1998). While there are burials found on islands in Samoa, many burials were singular graves underneath houses, nearby an ancient coastal settlement, or scattered in a nearby cave, but these are not definitively dated (Martinsson-Wallin, 2007). Unfortunately, the tools and other grave goods do not appear in the early or middle era burials, suggesting that either they did not widely use the tools, even though there is evidence of the contrary, burial goods were not as important a cultural phenomenon. The specialized basalt and metamorphic stone tools were too costly to make for them to be disposed so quickly, but we haven’t yet found the evidence that is still in the ground, or any combination of one or more of these options.

On the other side of the economic spectrum, however, there are the royal tombs that stand out in Samoa. One such tomb site, Lapaha, had the resources locally to create their own high-quality production line adzes, and could continue to trade for exotic material from the nearby islands in Tonga and the Society Island chain. The range of adze forms were prevalent in the grave; some metamorphic pebbles were made to look like the tools and flakes from an exotic area. A large (3.3 m) adze from a Society Island source dated to around A.D. 1550-1700, a hundred years after long distance Polynesian trade had stopped, was found along with pieces from the local Tutuila adze quarry within Samoa. It was namely with this high quality basalt rock and the craft specialization of those working and living nearby that Tutuila and the leaders of the area were able to accumulate their wealth, power, and influence, and thus, were able to dispose of it when they passed on (Clark et al., 2016).

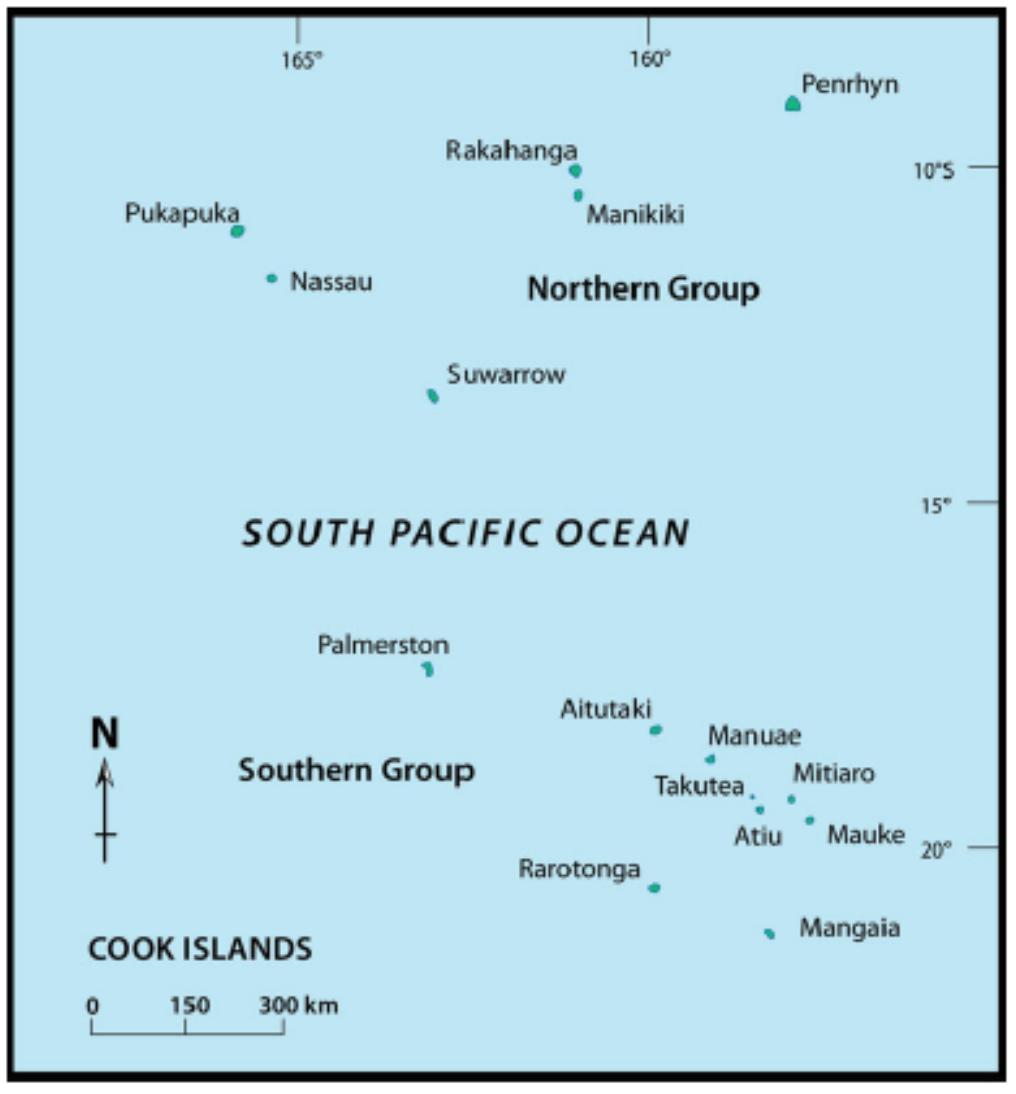

The Cook Islands, another home to early examples of the West Polynesian culture (2500-2100 BP) and the later transitional phase towards Eastern Polynesian culture, is where we can start finding burials with tools purposely buried alongside the human remains. This island region also contains sites of true Polynesian burial rituals and grave goods like the adze types usually found in transitional and western Polynesian societies. The largest island in the Cook Islands, called Rarotonga, is characterized by the geology of the high sloping volcano that formed it, giving it an “alteration of phonolithic and basaltic lava flows, producing fine grained stone suitable for adze making” (McAlister & Allen, 2017). While undated burials have been found in the coastal cemetery sites on the islands of Rarotonga, Mitiaro, and Mangaia these shallow burials do not include any types of grave goods (Walter, 1996: 78) and will not be covered. Burial sites on the Cook Islands include the Te Ana Rima Rau, Te Ana O Raka, Te Ana O Kuekue, and the Vaiari cave systems on the island of Atiu. The map in figure 13 below, from Clark, 2016, shows the many islands of the Southern Group, including Atiu, in relation to each other. While they are physically not far apart, the apparent burial cultures that we have been able to find are quite distinctive. On Atiu [figure 14] there are many cave systems, the entrances of which tend to be vertical drops, with multiple scattered burials can be found throughout. The largest example is in the Rima Rau cave, with over 600 skeletal remains identified, many naturally scattered against walls, but others still at least partially buried in purposeful positions, suggesting that some of the people received full burial rituals (Clark et al. 2016: 85).

Figure 13. Map

Figure 14. Map of Atiu with the names and locations of ten documented caves on the island (Steadman, 1991: 327 & Trotter, 1974: 96 in Clark, et al., 2016: 73).

Continuing on the discussion of Atiu, alongside Te Ana O Raka, said to be a chieftain’s family burial place, and Te Ana-o-Kuekue, not many artifacts were found alongside the bodies except for a dugout canoe in each, which stands in contrast to the combination of three burial caves of Vaiari (Steadman, 1991: 328, Kirch, 2017; 102-110). Vaiari’s burial caves not only contained between 30 and 50 scattered bodies in a more crowded space, one five-meter-long main chamber with a second that was inaccessible to archaeologists, but also canoe hulls, food remains, clothing, and tool-use artifacts (McAlister & Allen, 2017, Steadman et al., 2000). Most of the adzes, the pounder, the chisel, and the file made from coral are all broken or worn in some way. Aligning with the fact that the bones of the dozens of people had been swept around by the flooding of rain water, pieces have been broken, adzes un-hafted and blunted, and it has not been deciphered as to whether these effect were pre- or post-burial (Kirch, 2017; 102-110). These examples, however, are further evidence of a sort of social positioning building through time in the Cook Islands. The leaders and their families are buried in certain locations and later in time they have the means to be able to bury canoe-hull and the repositories inside, similar to a limited number of the wealthiest Viking leaders when they sent the long boats out to sea, demonstrating that they had little to no expectation for a lack of food, goods, the raw materials nor the time to make anything.

Figure 15: A. Map of the Society Islands B. Map of Maupiti Island with location on burial site on the islet Pae'ao (Emory and Sinoto, 1964: 145).

Reaching the Society Islands in the central point of Eastern Polynesia around 1000 AD, became a base for the people to continue trading and continue colonizing the furthest islands of the Polynesian archipelago: the Marquesas Islands, the Hawai’ian Island chain, and New Zealand (Hunt & Lipo, 2017). Maupiti is one island with an earlier site within the Society Islands that demonstrates the complete cultural evolution from Lapita to Western and then to Eastern Polynesian traditions, with the same ingenuity, which led the migrating peoples to continuously adapt to the environments in which they live. As Maupiti is the westernmost island group in the Society Island [figure 15] it follows that the burials on these islands would have been the oldest, if the people were exploring toward the east. Similar to the chiefly burials on Vanuatu, the major burial found in 1961 had many specifically placed artifacts and if we add the other burials found in the 1963 season the body position and orientation varied, but all graves contained some forms of grave goods (Emory & Sinoto, 1964). The authors of ‘Eastern Polynesian Burial At Maupiti’ make the argument that the specific artifacts that were found at the site, such as fishhooks, pendants, and various forms of un-elaborated adzes are reflective of a more “Archaic” cultural tradition which had ended soon after the Society Islands were initially settled around 1,500 years BP (Emory & Sinoto, 1964: 159-160; Hunt & Lipo, 2016).

Mangareva, Pitcairn and The Marquesas Islands of French Polynesia are all demonstrative of another further expansion through the Eastern Pacific [map figure 16 above]. While the dating of colonization is imprecise for these middle islands through the Y-shaped expansions, the range of settlement dates for Hawai’i, Rapa Nui/Easter Island, and New Zealand all match at A.D. 700-900 after the Society Islands around 1200-1400 years BP, which was found to agree with the dating of the earliest graves on those islands (Rolett 1998: 55-57, Green & Weisler 2002: 235-236). The nearest island group of these is Mangareva [map in figure 17 below], which contains a number of cultural deposits close to each other. Kamaka, the furthest island south of the main island Mangareva, has examples of these sites, designated GK-1, GK-2, and GK-3, the latter of which is locally known as Te Pito no Pokiri. The site GK-3 contains artificial pavement, a limestone slab platform, walls, and four burials all working their way in the direction of the coastal water line [figure 18 below]. While this burial site only has dates going back to A.D. 1600 this burial tradition is still pre-European contact and thus is reflective of the burial practices of the Mangareva peoples. Also to be recognized is that the two surrounding sites GK-1 and 2, along with the two other burials, are very close to the shelters that contain tool artifacts such as fishhooks, harpoons, and adzes dating back to A.D. 1200 on this island group, but between 200 to 400 years earlier in the Marquesas Island sites, leading Green to work out that he had not found the earliest evidence for this island and placed the settlement date between A.D. 600-800 (Anderson et al. 2003, Green & Weisler, 2002: 237). The tools themselves are dated to the period where long distance trade is still occurring between the island groups that make up the central Polynesian islands, which in itself leads to a generalization for items that are being shipped, so they could be used in various environments; but as we have seen on smaller island and atoll locations, the tools are more often not being placed in the graves, as they are likely too valuable to leave behind.

In the Marquesas’ island of Ua Huka, [figure 19] more recent archaeological investigation has taken place with three major sites: Hatuana, Hokatu, and the Manihina sand dune. The Manihina site specifically contains not only a habitation site, but also burials with grave goods. Within the Manihina Valley human skeletons were found a few stratigraphic layers above the evidence of potentially re-using habitation in the form of a large paved area, telling archaeologists that where people had once been living had been covered multiple times over the years and later used as a cemetery. This in particular may not be indicative of anything, but this site does show that there were rituals which had to be followed, “exposure and decomposition of bodies before burial, taking of skulls and some bones, position of burial, association with artifacts or animals… and it seems that some bodies were wrapped, probably in tapa” (Conte, 2002: 264). These tool use artifacts found in this mixed-use house and burial site run the gamut of fishhooks, sinkers, and adzes, everything that would have been useful to the inhabitants, one of which was dated to 480 ± 100 BP or between A.D. 1480-1680, to rework and reuse (Conte, 2002: 261).

Hawai’ian Islands

The furthest point north that the Eastern Polynesian culture reaches to is the Hawai’ian Island chain [located at the top of the zone in figure 20 map above]. In this location the range of habitational ecosystems grows and the ability for specialization leads to a burial culture that expanded one the previous island practices. The tool kit here started out generalized, as we can identify in much of the finds from early sites around Polynesia and the raw material had been brought vast distances, but over time the local materials were being worked with and the tools that were being made were being shaped for particular functions by specialists (Emory 1968, Sinoto, 1979, Kirch 1985, Leach & Leach 1979, Allen 2010). While the people in Hawai’i did create their own style of adze, it could still be seen as similar to the others that are found in the other remote areas of Polynesia, both in and outside burials.

The island of O’ahu has some of the oldest sites, one being known as Bellow’s Dune [located on the map in figure 21 above], though four sites exist from the time range of the settlement, from AD 600 to between 1100 and 1200 (Kirch, 1970: 233, Tuggle & Spriggs, 2000: 166). The Halawa Dune Site has oval and round houses and adzes found, with similar examples of both found in the Marquesas, Samoa, Tonga, the Society Islands, New Zealand, etc. suggests connections from the Melanesian influences while adapting to the local environment (Kirch, 1970: 233-234).

Like in the wealthy areas of Samoa and the Society Islands, the high-quality stone from a few quarry sites in Hawai’i led to the leaders having many prestige items in their burials. As a widespread people across all the larger Hawai’ian islands, there were many places where people could have been buried. The ruling class had their prestige and could ensure that their family members were buried in caves/lava tubes around the islands, underneath monumental works, or inside heiau (platforms) while the commoners had to find areas away from their farming land to bury their relatives, such as in the sand dunes or under the bases of their homes (Cordy 1974, Kirch 1985). Depending on where the commoners lived, they would have a craft or skill in which they would specialize, giving all items made by those people and the younger generation they teach a specific method, leading to a particular style. And with the trade between the Hawai’ian Islands at first and on each individual island later, the system would have become self-contained and self-sufficient, and with the excess and possibility of wealth and status personal artifacts would become much more common amongst the majority of burials (Kirch 1985, Tuggle & Spriggs 2001, Clarkson 2015).

Focusing on the cave and lava tube burials, the remains and goods often dated to AD 1250 – 1750, while the sites with dune burials could be dated back to around AD 650 – 1300 (Kirch, 1982: 462). We can find scores of human remains within Kalahuipua’a Cave on the largest island, Hawai’i. Part of this area was particularly for the community members with less wealth, as there were not as many grave goods. In another section, Forbes’ cave, high status graves were found as well, with bodies laid out inside canoes alongside portable wooden sculptures. In another cave along a cliff face of Waimea Valley, O’ahu a large group from a wealthy family was buried with wooden canoe hulls, food bowls, mats, and cloth, seemingly suggesting that ritual would be telling the living members to send things that the deceased would need for a nautical journey (Kirch 1985: 238-239).

As for the more recent sand dune burials, grave goods are not typical, though do occur, like in the Bellow’s Dune Site. An example of this being within two female and one out of 355 individuals (Kirch, 1997: 240). The women were given, as ornamentation, male grave in the Keöpü, North Kona, Hawai’i, burial site; in these particular few were there was jewelry to wear and the men were buried with a cache of fishing tools such as: hooks, sinkers, and tools for manufacturing more, making the grave goods fit more specifically to the individual (Han & Collins, 1983 cited in Kirch, 1997). Burials could be further specified when the burials lay underneath the family home, a common practice throughout the history of Polynesia. Examples of these are found in the Bellow’s Dune site as well, and the Halawa Valley site (Figure 22) on Moloka’i, which also contains hearths with layers of material that has been dated from between AD 600 to 1800 (Kirch, 1997: 240, Kirch, 1971: 230). Local adze manufacturing quarry sites along with the abundance of people living near the ocean could retrieve the rock, shells, and animal bones to be shaped into various tools.

Figure 22. Map of the Island of Molokai with Halawa located, and in relation to the other Hawai'ian Islands (Kirch, 1971: 231).

Mauna Kea adze quarry complex has been described by Handy as a “consecrated industry” or a manufacturing activity in which ritual plays a massive role (Handy 1927: 282). Mauna Kea’s was a late site, with four of the small rock shelters dating to AD. 1424 – 1657 (McCoy, 1976: 138). Adze manufacturing is a specialized craft, a particularly honed skill everywhere in the world, and this is especially seen in Hawai’i. In the Mauna Kea quarry, there is not only debitage, material created from manufacturing lithic tools, and unfinished adzes and cores scattered around the site, but also rock shelters and specially made shrines, both with perishable food and non-perishable goods, and finally nearby burials (McCoy et al. 2012: 415-416). Those buried nearby are believed to have been the craft specialists and their families, who lived near the adze quarry. They were buried underneath the floors of their own houses and were found with a few of the adzes that had been carved (Kirch 1985: 304). As the basalt quarry itself is at a high altitude (3,355 – 3,780 meters above sea level) and is not easy to get to quickly, there would have been a permanent base for people on the summit to continue working every day the harsh weather conditions would allow, and then transport finished pieces to the canoes down the mountain (Kirch, 1985: 179-180). Few finished adzes from this area have been found across the islands, whether in either house sites or burials, and are representative of later works. The ones in the burials are particularly similar, representing a continuation of the standardization in form and use during the Polynesian developmental phase between AD 110-1300, with the most recent sites here earlier than the 1800s (Kirch, 1985: 20, 184 & Millis, 2014).

Figure 23. Mauna Kea and other locations of adze quarries on the island of Hawai’i, the largest island in the Hawai’ian chain (McCoy, 1990).

The colonization of the Hawai’ian Islands aligns with the standardized Polynesian traditions, affecting the building of tools, houses, and communities. Most of the adzes that are found fit into this timeline of AD 600 - 1750, with the pieces made from high quality basalt being from the middle to the latter dates (Kirch, 1997 & Millis, 2014 & McCoy, 2017).

Summary

The adze, a commonly utilized tool, has been found in Polynesian burials because of the communities’ ascribing symbolic meanings of status due to the tool’s ability to shape the Earth for human control. To summarize, the ornamentation of these tools and their placement within the burials created a normalized pattern for the generations to follow. As shown with examples from the world over, ornamentation and their various grave goods are linked to the communities’ perceptions of the deceased. While the person who is dead does not have a say in what is buried with them, the family or community do control what they show-off, and therefore how their family will be perceived by all other community members. The social relationships between the specialists and the community, and the relationships between the specialists and their family are at the heart of this practice. Not everyone could go out and make an adze, in the Pacific Island region the spirit of the adze making was for the peoples’ ancestors. This knowledge and specialization that was passed down the family line was the basis of the burial practice. Families wanted all to know that this person, part of their community was a part of the tradition, that they could shape the Earth to fit them instead of the other way around, while still being inexorably linked.

This would grant ‘status’ to the person with whom the tool was buried and to the tool itself. Like the hammer and axe from the Nordic and Western European cultural traditions, the adze has proven itself to be a robust tool for altering items as needed. Unlike a hammer, from a hammer stone, the idea for shaping the environment had to have come before the tool was “invented”. Because a hammer involves only hitting one thing with another to move or break the initial object, while an adze or axe involves shaping material to later use that particular shape to create something else. This symbology is continuously placed on Thor’s Hammer, Mjölnir, and a higher number of axes of mythology, one owned by the Norse god Forseti (even though the axe is also sometimes attributed to Thor as well) for example, and the Sumerian God Enlil’s creation of a mattock (combination of adze and pick-axe) demonstrates the later ritual importance of these tools for creation and defense (Krogmann 1964, Hooke 2004).

From this, I will be continuing with various societies’ oral histories and the more mythological based data that will be increasingly analyzed within the next chapter. I will also demonstrate that the organizational methods of this paper are contingent on the collecting of research and the presentation of each aspect as the following. First, I will locate burial sites around the world wherein tools appear as grave goods. Second, I will research the societies’ culture that used those tools, through the examination of the mythology for stories about or featuring the tool. Third, compare the use of the tools in relation to the deity who wields it. Fourth, I will discover the connections archaeologists made between the tools’ power and its interpreted role in nature.

wo female and one male grave in the Keöpü, North Kona, Hawai’i, burial site; these particular few were three out of 355 individuals (Kirch, 1997: 240). The women were given, as ornamentation,

Figure 22 - Map of the Island of Molokai with Halawa located, and in relation to the other Hawai'ian Islands (Kirch, 1971: 231).

jewelry to wear and the men were buried with a cache of fishing tools such as: hooks, sinkers, and tools for manufacturing more, making the grave goods fit more specifically to the individual (Han & Collins, 1983 cited in Kirch, 1997). Burials could be further specified when the burials lay underneath the family home, a common practice throughout the history of Polynesia. Examples of these are found in the Bellow’s Dune site as well, and the Halawa Valley site [map figure 22 above] on Moloka’i, which also contains hearths with layers of material that has been dated from between AD 600 to 1800 (Kirch, 1997: 240, Kirch, 1971: 230). Local adze manufacturing quarry sites along with the abundance of people living near the ocean could retrieve the rock, shells, and animal bones to be shaped into various tools.

Figure 23 - Mauna Kea and other locations of adze quarries on the island of Hawai’i, the largest island in the Hawai’ian chain (McCoy, 1990).

Mauna Kea adze quarry complex has been described by Handy as a “consecrated industry” or a manufacturing activity in which ritual plays a massive role (Handy 1927: 282).

Mauna Kea’s was a late site, with four of the small rock shelters dating to AD. 1424 – 1657 (McCoy, 1976: 138). Adze manufacturing is a specialized craft, a particularly honed skill

everywhere in the world, and this is especially seen in Hawai’i. In the Mauna Kea quarry there is not only debitage, material created from manufacturing lithic tools, and unfinished adzes and cores scattered around the site, but also rock shelters and specially made shrines, both with perishable food and non-perishable goods, and finally nearby burials (McCoy et al. 2012: 415-416). Those buried nearby are believed to have been the craft specialists and their families, who lived near the adze quarry. They were buried underneath the floors of their own houses and were found with a few of the adzes that had been carved (Kirch 1985: 304). As the basalt quarry itself is at a high altitude (3,355 – 3,780 meters above sea level) and is not easy to get to quickly, there would have been a permanent base for people on the summit to continue working every day the harsh weather conditions would allow, and then transport finished pieces to the canoes down the mountain (Kirch, 1985: 179-180). Few finished adzes from this area have been found across the islands, whether in either house sites or burials, and are representative of later works. The ones in the burials are particularly similar, representing a continuation of the standardization in form and use during the Polynesian developmental phase between AD 110-1300, with the most recent sites here earlier than the 1800s (Kirch, 1985: 20, 184 & Millis, 2014).

The colonization of the Hawai’ian Islands aligns with the standardized Polynesian traditions, affecting the building of tools, houses, and communities. Most of the adzes that are found fit into this timeline of AD 600 - 1750, with the pieces made from high quality basalt being from the middle to the latter dates (Kirch, 1997 & Millis, 2014 & McCoy, 2017).

Summary

The adze, a commonly utilized tool, has been found in Polynesian burials because of the communities’ ascribing symbolic meanings of status due to the tool’s ability to shape the Earth for human control. To summarize, the ornamentation of these tools and their placement within the burials created a normalized pattern for the generations to follow. As shown with examples from the world over, ornamentation and their various grave goods are linked to the communities’ perceptions of the deceased. While the person who is dead does not have a say in what is buried with them, the family or community do control what they show-off, and therefore how their family will be perceived by all other community members. The social relationships between the specialists and the community, and the relationships between the specialists and their family are at the heart of this practice. Not everyone could go out and make an adze, in the Pacific Island region the spirit of the adze making was for the peoples’ ancestors. This knowledge and specialization that was passed down the family line was the basis of the burial practice. Families wanted all to know that this person, part of their community was a part of the tradition, that they could shape the Earth to fit them instead of the other way around, while still being inexorably linked.

This would grant ‘status’ to the person with whom the tool was buried and to the tool itself. Like the hammer and axe from the Nordic and Western European cultural traditions, the adze has proven itself to be a robust tool for altering items as needed. Unlike a hammer, from a hammer stone, the idea for shaping the environment had to have come before the tool was “invented”. Because a hammer involves only hitting one thing with another to move or break the initial object, while an adze or axe involves shaping material to later use that particular shape to create something else. This symbology is continuously placed on Thor’s Hammer, Mjölnir, and a higher number of axes of mythology, one owned by the Norse god Forseti (even though the axe is also sometimes attributed to Thor as well) for example, and the Sumerian God Enlil’s creation of a mattock (combination of adze and pick-axe) demonstrates the later ritual importance of these tools for creation and defense (Krogmann 1964, Hooke 2004).

From this, I will be continuing with various societies’ oral histories and the more mythological based data that will be increasingly analyzed within the next chapter. I will also demonstrate that the organizational methods of this paper are contingent on the collecting of research and the presentation of each aspect as the following. First, I will locate burial sites around the world wherein tools appear as grave goods. Second, I will research the societies’ culture that used those tools, through the examination of the mythology for stories about or featuring the tool. Third, compare the use of the tools in relation to the deity who wields it. Fourth, I will discover the connections archaeologists made between the tools’ power and its interpreted role in nature.