Apophis vs. Apep: Into the Serpent’s Lair

This is one of my favorite shows, and yes I’m doing my favorite things, because I can. I didn't grow up with this series, though it started in 1997. I didn't watch it until high school, or at least late Junior High. I always loved how Daniel Jackson would put in so much of himself into all of his work and I wanted to emulate that and how he tells everyone about the the gods and the cultures that they're encountering or the gou-auld that they're encountering just based on what the god actually did in mythology so I got to the point where I want to check and see if any of that's accurate because some of it might not be quite right especially when they turn beloved Gods into evil monsters that basically that's what they're called are they're parasitical monsters that take over individuals to enslave them and thousands people sometimes do genocides and they don't care because they are evil if that's specially what the show is implying. But, especially when you get to the Asgard and how they're all benevolent or at least mostly benevolent grays the aliens they are all Norse so what I wonder is the show saying about or what subtext can be gleaned from what the show could be saying about older cultures.

Now if I was doing this completely in order I would start with Re from the movie but I haven't seen the movie in a long time and I like the show way better so I'm going to start with my favorite villain, Apophis, who will not stay dead…! He keeps coming back, which is actually mythologically important and I will get to that so sit back relax and enjoy the first episode of what will be my continuing series on the Stargate SG-1 mythology versus series… I got to think of a different name.

My name is Renée, you're listening to Detours and Artaeology, and this is episode 1, Apophis versus Apep: Into the Serpent’s Lair.

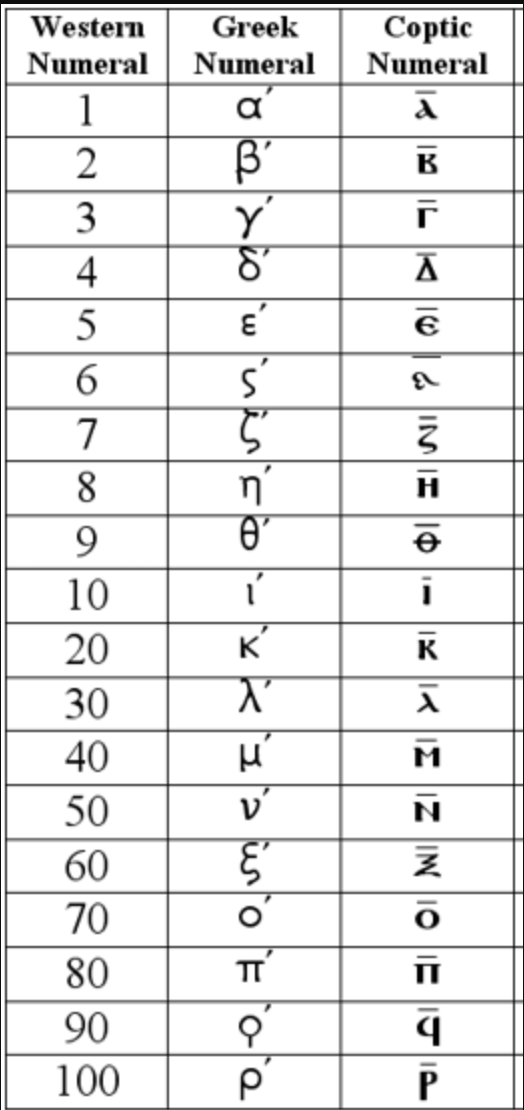

The first, most glaring difference that I bet most people would never ever know… his name. Apophis is the Greek name, Apep is the Egyptian. So, if the show wanted to be accurate for the aliens that stole the ancient Egyptians the aliens would only know the god as Apep. Although since there are goa’uld called after the Greek gods, maybe they learned what people then referred to the Egyptian dieties as. But why would the older ones care to change their names? Also, random heads up, in texts Apophis also has many other names; Aapep, Am, Apepi, Aman (not to be confused with Amun), Amen, Apopis, Beteshu, Hau-hra, Hemhemti, Hem-taiu, Iubani, Karau-anememti, Kenememti, Khak-ru, Khermuti, Khesef-hra, Nai, Nesht, Qerneru, Qettu, Rerek, Saatet-ta, Sau, Sebv-ent-seba, Sekhem-hra, Serem-taui, Sheta, Tetu, Turrupa, Uai, Unti (Turner 2000: 61; Hill 2010; Encyclopaedia Britannica 2025).

To get the contrast between the two versions, we first have to discuss the original. Highlighting the way mythology is repurposed in popular culture, with certain themes and traits retained while others are adapted to fit modern storytelling and genre conventions.

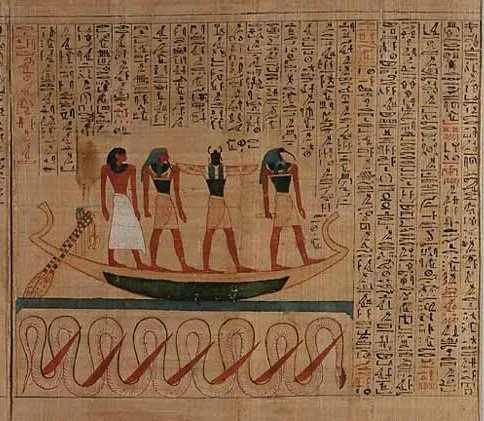

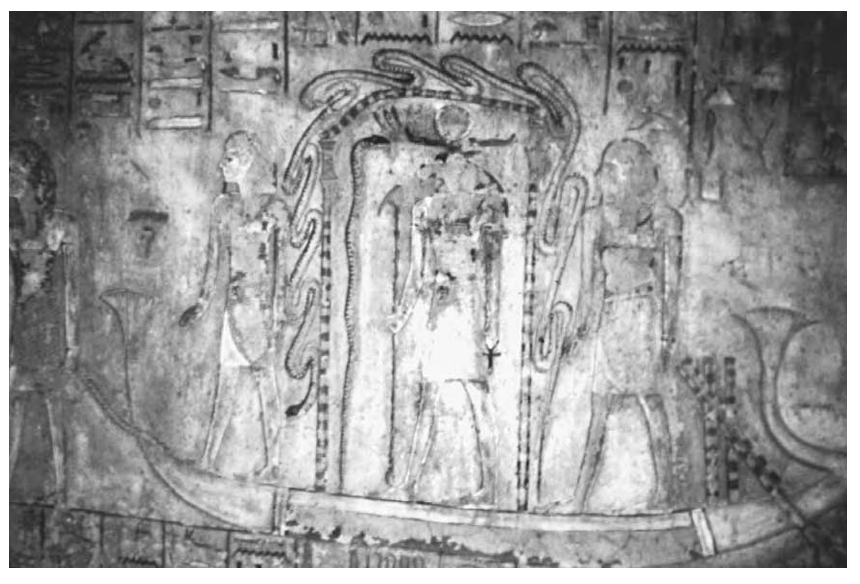

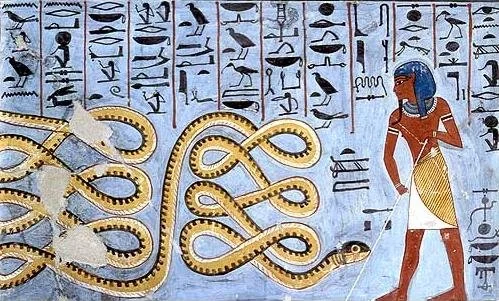

Figure 1. “In Egyptian mythology, Apep was a serpent demon who represented the forces of chaos, death, and disorder. As such, he was the mortal enemy of order, personified as the goddess Ma’at, and light, as incarnated in the form of Ra. This adversarial construal of the demon is evidenced in various surviving texts from the Middle Kingdom period onwards (ca. 2000-1650 B.C.E.), including the Book of the Dead and the Book of Gates—both of which are concerned with the geography and mythology of the underworld.”

In the image Apophis in tied down to labeled hooked between Anubis (jackal - left) holding the feather of Ma’at and Thoth (baboon - right)(Photo by: Pictures from History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images).

Part 1: The Orginal Serpent

Let’s start with the original Apophis (Apep) in Ancient Egyptian Mythology.

His role in Egyptian cosmology was the central concept of chaos…

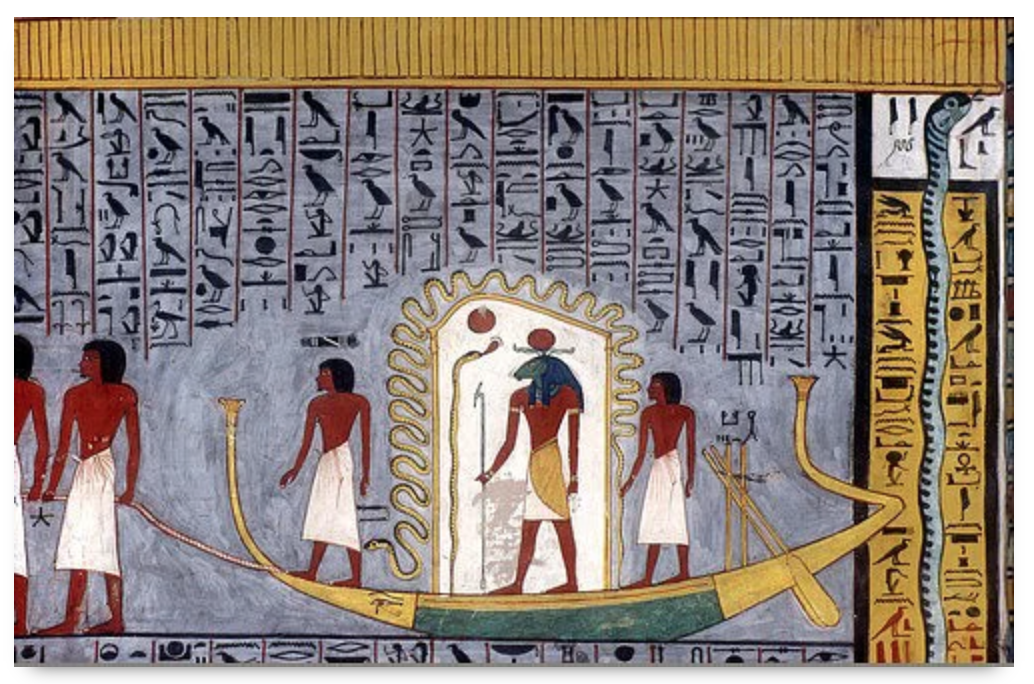

He was the constant antagonist of Re. Apep’s struggle against Re was seen as a cosmic battle between light (order) and darkness (chaos). Part of the myth that was a central part of the Egyptian night, was that Apep attempts to swallow the sun during its journey through the underworld (Duat), but Re and his followers (other gods, such as Set, Thoth, other gods, or those people rich enough who painted the scene on their tomb walls) would fight him off to ensure that the sun rose again each day.

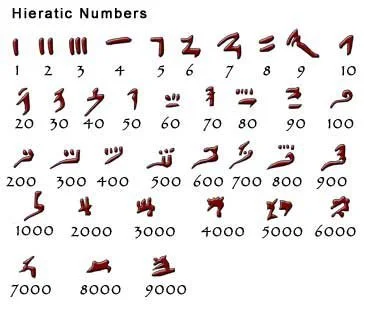

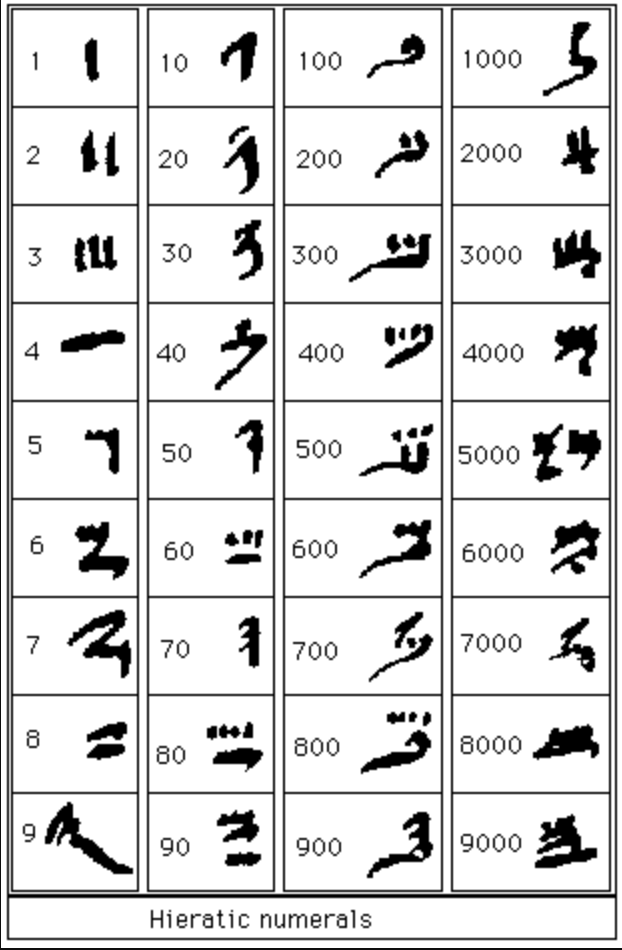

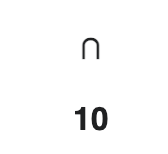

While I’d like to say it was a specific hour each night that Apep encountered Re while he’s on his ritual journey through the underworld’s gates of night on his divine barge, we aren’t COMPLETELY certain. It is supposed to be either the seventh or tenth hour, but writings seem to contradict eachother. This isn’t uncommon, of course, at first I thought it might be a translation error somewhere along the line, and the symbol for 7 (sejef or sáfḫaw (masc.)/sáfḫat (fem.)) could either be seven vertical lines or it could look almost like a 3 with the bottom line partly scratched off while the 10 (medyu or mū́ḏaw (masc.)/mū́ḏat (fem.)) looks like a curve-up horseshoe, or a hobble for cattle, but could be carved/written diagonally (Figures 2-7)(Rubin 2004: 481;Allen 2010: 102; Faulkner 1962; Loprieno 1995: 71). So I think that could be the issue, if part of the carving was a bit worn off or happened to get extra scratched up in the wrong place (or the right place) one number could easily be mistaken for the other. Otherwise, it could be just a case of changing mythology depending on the area or time period, or just some scribe got the hours mixed up.

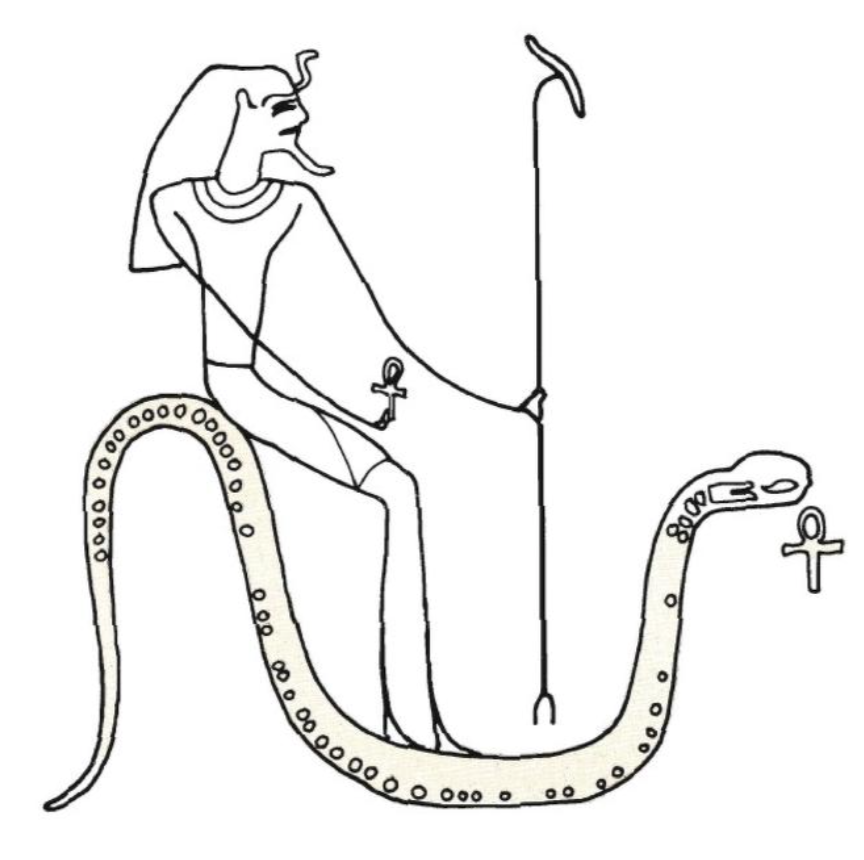

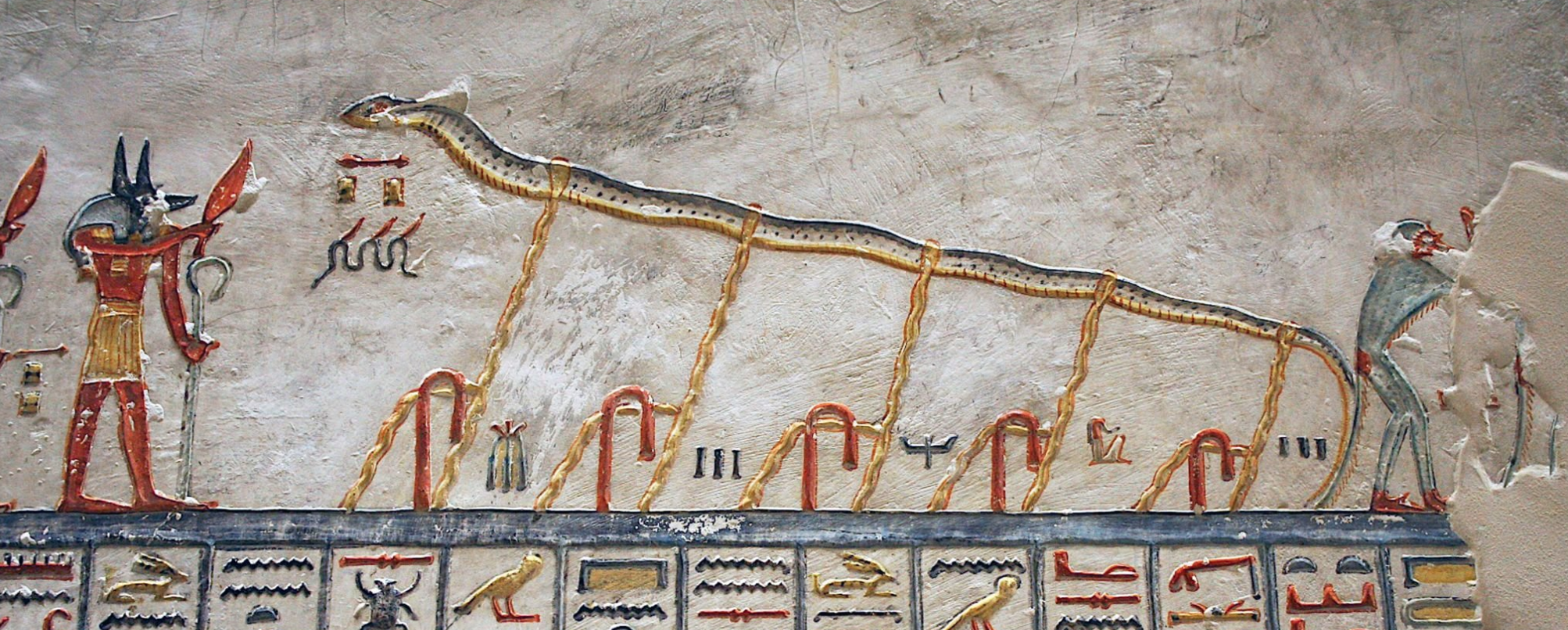

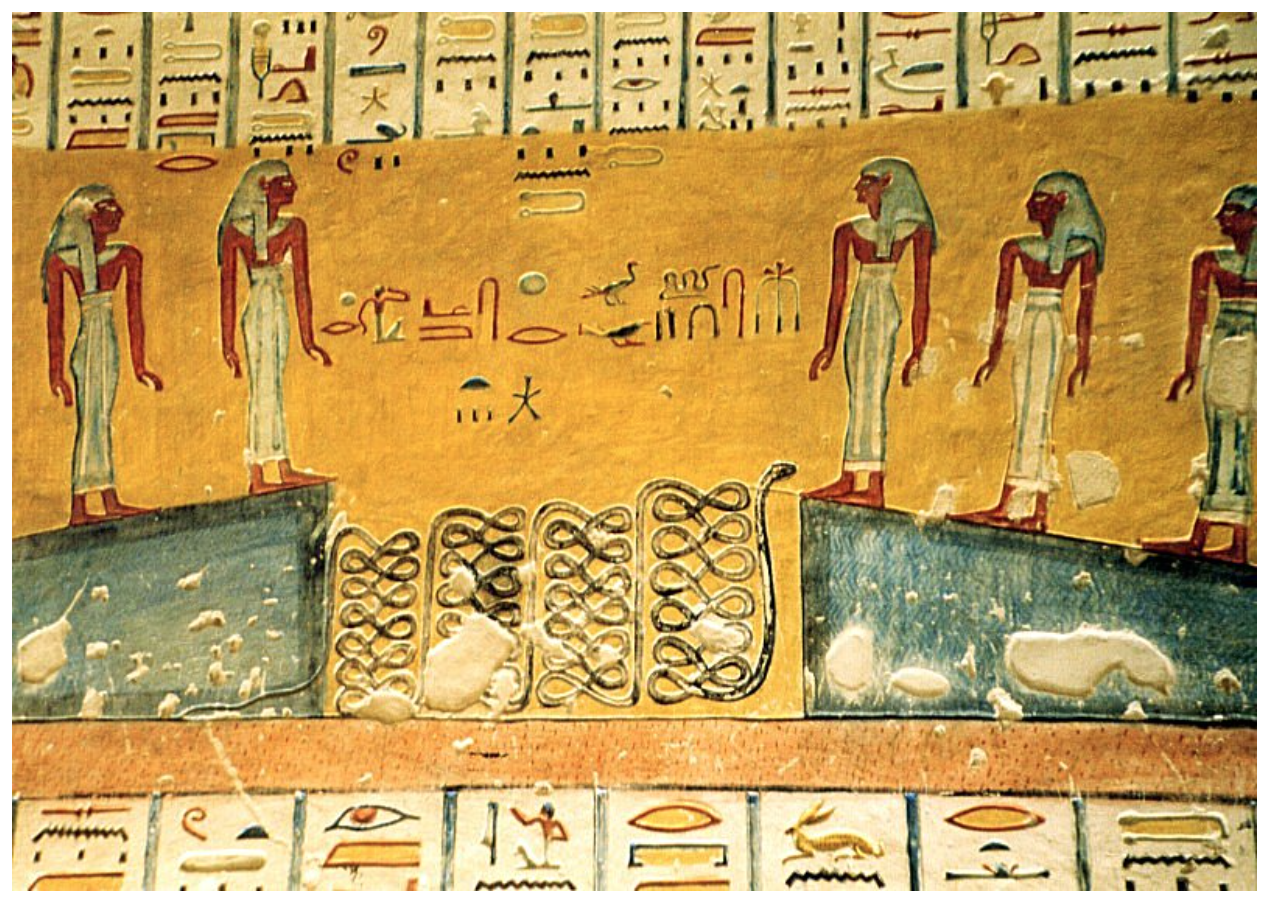

Extra: In one text, Apep is shown coiled up in his realm, the Duat, in a part of a scene of the fourth hour of the Book of the Gates from KV2, tomb of Rameses IV (king during the new kingdom). One interpretation of image is that "the time is like a serpent, of which the nocturnal hours are born like goddesses. After its trip they are devoured again by the serpent. The blue triangles represent the water in the underworld" (Figure 8)(Sutherland 2001).

Figure 8. Image credit - contrib. - Schreibkraft - CC0 1.0

The serpent sometimes swallowed the souls of the dead as they traveled to the afterlife, destroying them unless saved by other gods. Even the gods were not safe from this Apep (Rose 2001). Egyptian underworld texts like the Book of Gates and the Book of Caverns show detailed maps of the underworld, with many gates (called "hours" or "caverns") filled with monsters and gods. These books show that even the gods were vulnerable, as they describe the sun god’s struggles against Apep (Pinch 2004: 25).

Apep stands for death, night, and storms—the dark parts of life. He lived deep in the Nile when not in the underworld, causing hidden sandbanks that were dangers for boats (Rose 2001; Pinch 2004: 106). Apep also caused frightening events like eclipses when he succeeded and swallowed Re and the solar barque, but Apep was always forced to regurgitate the deity, allowing for the sun's re-emergence (Rose 2001). In some variations of this myth, the regurgitation of the sun was seen as a metaphor of rebirth (Littleton 2002). His movements could cause earthquakes, and his eyes were feared, reminiscent of later basilisk legends (Wilkinson 2003: 223; Pinch 2004: 106). That’s why hymns for the sun often describe Apophis being hurt by lances or knives (Lurker 1978).

The Origins and Timeline

Predynastic Period (c. 5000 to 3100 BCE)

The earliest references and depictions of Apep date back to the Predynastic Period. Found on a Naqada I (c. 4000–3550 BCE) C-ware bowl, a snake painted on the inside rim, who is believed to be Apep was painted alongside other desert and aquatic animals as an enemy of a deity, seemingly a solar deity, who is ‘invisibly’ hunting in a big rowing vessel (Wolterman 2002). The snake on the inside rim is believed to be Apep.

The few descriptions of the origin of Apep in myth usually says that he/they/it was born after Ra, usually from his umbilical cord. Geraldine Pinch claims that although first mentioned in the 21st century BCE a much later creation myth explained that “Apep sprang from the saliva of the goddess Neith, [‘Mistress of the bow’ the goddess of warfare and motherhood, shown with bow and arrows protective of the Royal sarcophagus and canopic chest (p.170) - mother of Sobek (Fleming & Lothian 1997: 62.) Re, (Lesko 1999: 60–63) Apep,(Fleming & Lothian 1997: 62.) Tutu, (Wilkinson 2003: 183) and possibly Serket - ] when she was still in the primeval waters. Her spit became a snake 120 yards long" (2004).

This myth shows that Apep is commonly believed to have existed from the beginning of time in the waters of Nu or Neith of primeval chaos (Bunson 2002; Wilkinson 2003). This and similar versions story of Apep’s birth may not have been a common idea until the Roman Era. since it wasn’t seen on a temples until the 2nd century. Another version was also recorded in the second century BCE on the walls of Esna Temple, located about 50 km south of Luxor (ancient Thebes). The carvings told that at the moment when the sun god Ra appeared, the sinister Apophis (at this point they might have carved Apophis not Apep) was also born. According to the concept of duality and a long history of homeopathy, evil is necessary as a counterpart to good. Ra ruled over days, crossing the sky daily in his solar barque accompanied by other gods and the dead pharaohs. He traveled through the afterlife by night, a dangerous abode of many serpents including Apep, whose time and place of action were hidden behind some mountain, depending on the myth. During his journey through the underworld, the sun god Ra (but mainly the other gods) fought off monsters in specific hours, which was necessary because according to the principle of Ma’at, or order against the chaos represented by monsters, this struggle had to happen. (Hill 2010).

Rather than being a god, Apep is seen as a force that threatens the natural order, which continues throughout Egyptian cultural tradition. Still in some myths, possibly the earliest, the unnamed monstrous serpent embodied the destructive aspects of chaos, constantly threatening to reduce everything back to the primeval state of singularity or 'oneness'; in this way, even before creation existed, the world contained the basis of its own eventual destruction (Pinch 2004: 58). Thus, according to some myths, Apep was neither born nor created. He simply was an embodiment of the forces churning within the Nun [which is NOT the name of the goddess of the sky, which is NUT] (McCormick n.d.).

Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE)

Apep's name and early mythological functions are then mentioned in pyramid texts from the Old Kingdom, around 2400 BCE (Apophis: every ancient Egyptian's greatest fear after death, n.d.). Unlike what artistic depictions made today might show, initial depictions of Apep are simple and often show him as a serpent, symbolizing chaos, as the being opposed to the orderly daily cycle of the sun, generally during the big fight against the barge [figures from various kingdom periods] (Figures 9-15). The cultural implications during this period were mainly focused on maintaining harmony and order in the world. Apep’s existence reflects the real-world concerns of the ritualistically minded Egyptians in maintaining the cosmic balance. Either Re or Atum would encounter the serpent from the seventh hour of the Amduat (the duat). Like the sun god Re, with whom he was associated, Atum was constrained to pass through the netherworld regions in the cycle of death and regeneration.

Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE)

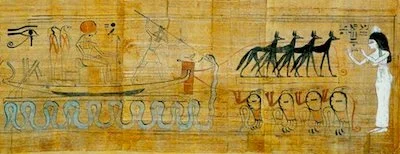

This is the major period in which Apep appears as an Enemy of Ra specifically. Apep is named in several spells of the Coffin Texts, a set of funerary spells written on the coffins of important people during the Middle Kingdom period. Apep's role as an enemy of Ra becomes more prominent in religious texts from this period, especially in the "Amduat" and "Book of Gates." The serpent attacks Ra's solar barque during its nightly journey through the underworld (Duat). The other riders protected the universe from darkness by forming a shield around Ra’s boat to keep him safe from Apep’s attacks. They then used their magical powers to defeat Apep by shooting magical arrows at the serpent and using spells to send him away from the realm of the gods. The Book of Gates also shows the role of the dead person in this fight, where the soul of the dead is seen as a helper of the gods in defending Ra’s boat. In the end, the text suggests that the dead can earn their place among the gods by helping to defeat Apep and keeping the balance of the universe.

This story shows the victory of order over chaos and is just one example of the many ceremonies and ideas the ancient Egyptians used to protect themselves from the evil forces that they firmly believed threatened their world. (Apophis: every ancient Egyptian’s greatest fear after death n.d.). During this time, the theological development of the fear of Apep aligns with the Egyptian belief in the continual fight between order and chaos, reflecting anxieties surrounding the stability of the kingdom and the afterlife.

Heavy use of Apep in royal propaganda by Pharaohs began to associate their own struggles against rebellion and disorder with Ra’s daily defeat of Apophis, thus linking the divine order with political stability.

New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE): Apophis as the Ultimate Chaos Entity

Apep appears in the "Book of the Dead" showing that knowledge of him was well known and widespread at the time as he becomes a central figure in funerary texts. His constant defeat symbolizes the triumph of the soul over chaos and death, linking him directly to the afterlife boat ride as everyone’s mythical punching bag. Because of this rituals and spells were developed by priests of Re and other religious groups to protect the deceased from Apep on their journey, such as in the "Chapters of the Book of the Dead" which include prayers to ward off Apep and ensure safe passage through to the afterlife. While it may seem that Apep is an easy foe to defeat because of all of the art showing his defeat, it is almost the opposite. The reason for including the coffin and pyramid texts, “the Book of the Dead”, on walls or coffin is BECAUSE he was so difficult to fight. As a cheat sheet, anything written, carved, and painted became reality on the journey to the afterlife and the afterlife itself. Therefore, pharaohs/the incredibly rich and powerful people who could afford the work chose the hardest tasks to achieve on their route to include in petroglyphs/pictographs so they could actually win (Figure 16).

As a popular myth and its symbolism, Apep is now seen as a symbol of all that threatens not just the cosmic order, but personal security. His conflict with Ra grows in mythological complexity, and he is portrayed as more than a physical snake—he becomes a metaphor for universal disruption. Apep had certain hiding places, one was supposed to be in a crevasse(?) within the “Forth Region of Night” (Figure 8) and another was the so-called "Tenth Region of the Night," from where he wanted to attack Ra from behind a mountain just before dawn when the sun god was on his way to begin his daily journey across the sky. Apeps different hiding places gave him the name "World-Encircler" (Figure 167.

Figure 17. Apep in the tomb of Ramesses III. [Shown as a 3 headed hydra type creature with wings] Credit: Adobe Stock - Vermeulen-Perdaen

The Late Period and Graeco-Roman Period (c. 664 BCE–30 BCE):

During the decline and reinterpretation in the later periods, particularly under Greek and Roman influence, Apophis’ (which would be the name officially now) role is reinterpreted within broader Mediterranean religious traditions. There was a book put out called “The Book of Overthrowing Apep” in 305 BCE. This text contains a long series of spells to defeat and capture “the demon Apep, and thereby sustain the power of the great god Rê”, with a section for a much briefer set of incantations.

“[T]he spirits of the Dead were expended to join in the struggles against Apep and the rituals are performed in temples to ensure his defeat. The Book of Overthrowing Apep the most terrifying deity in the Egyptian Pantheon was invoked to combat the chaos Serpent and destroy all the aspects of his being, such as his body, his name, his shadow, and his magic”

(Borhouts 1973: 114-150; Hornug 1982 103-113).

The effect of the spells was heightened by the use of red ink in some places, as reproduced on the webpage. The text has been preserved in the same papyrus scroll as the Songs of Isis and Nephthys. A portion of the text near the end:

“Thus says Tefenet: The water shall rage (?) against thee, and chastisement shall be on the water whence thou hast issued. Shu thrusts his spear into thee, and thou shalt submerge and not emerge again, O ʿApep thou foe of Rê. Be thou spat upon, O ʿApep - four times - be ye spat upon, O all ye foes of Pharaoh, dead or alive.”

(Faulkner 1937/1938)

After this passage, there are two Books of Felling, when Apep’s death, rather his defeat, is celebrated (Faulkner 1937/1938).

The translation is by R.O. Faulkner (JEA, 1937 & 1938), and the full text includes passages of the creation of the world. Even after this, Apep is still seen as a force of chaos, but his opposition to Re becomes more metaphorical, representing larger cosmic or existential struggles, much like it was in the very beginning of his belief. A reinterpretation of mythological themes emerges as the core concept of Apep mythology begins to blend with other serpent and dragon myths from surrounding cultures, reflecting Egypt's expanding cultural exchange with the wider world. As would be obvious, since the Greeks and Romans didn’t worship him, there was a decline in Apophis worship. As Egyptian polytheism gave way to foreign rule, the worship and mythological importance of Apophis faded, although the symbolic struggle between order and chaos persists in the backdrop of Egyptian thought.

Serpent Imagery:

Apep, being chaos himself, was most commonly depicted as a giant serpent or snake, symbolizing his connection to chaos and danger. Snakes in ancient Egypt were sometimes associated with evil forces, as well as with destruction and fear.

“Demon of chaos, who had the form of a serpent and, as the foe of the sun god Re, represented all that was outside the ordered cosmos” (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2025). Apep wasn’t like the serpents that symbolised divinity or royalty (such as Wadjet or the Uraeus), because he threatened the underworld or night and symbolised evil (The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, 2025). “[A]n Egyptian proverb states: ‘one should welcome the Uraeus and spit on Apophis’ ” (Pinch 2004:106). The Uraeus is a symbol for the goddess Wadjet. She was one of the earliest Egyptian deities and was often depicted as a cobra, as she is the serpent goddess (Alchin n.d.). The idea of the Apep snake may have come from the African python, with an open mouth wide enough to swallow a person—‘his eyes were feared and his roar was said to be “terrible” ’ (Pinch 2004: 107). And, as mentioned before, he was probably the snake demon who tried to swallow (the Primeval Waters) but was forced to cough them up (Pinch 2004: 107). [Sometimes Apep was described as a “huge crocodile”, but usually a giant snake (Pinch 2004: 106).]

Let Them Fight

The fight changes over the centuries. Set, while being an adversary of Osiris and Horus in later myths, in older tales, he would be the one defeating Apep (figures 9 and 13). In the Middle Kingdom, the humans who join Re in death would protect him and kill Apep until the next night (remember: he keeps coming back because chaos is eternal). Apep was a central figure in various Egyptian rituals designed to ward off evil, particularly in the context of protecting the king and ensuring cosmic order. The "banishment of Apep" rituals were important in Egyptian religious life, symbolizing the king’s role as a protector of order against the forces of chaos because “The Egyptians believed that the king could help maintain order of the world and assist Re by performing rituals against Apep” (Pinch 2004).

It’s not over, there are MANY animal variations in different versions of the myths.

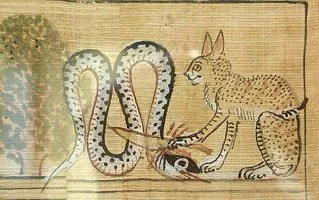

It was in cat form that the daughter of Re assisted her father in an epic battle against the chaos monster Apep. One terrible night Re himself took the form of the Great Tom Cat and fought the Apep serpent under the ished tree at Heliopolis “on the night of making war and driving off the rebels". He sliced up Apophis with his knife and split the ished tree in two, creating the twin trees of the horizon (Figures -)(Delvaux & Warmenbol 1991; Malek 1993; Pinch 2004: 134; PS 4).

Figure 18. Apophis slain, from the Papyrus of Hunefer (BM inv. no. EA 9901,8); painted papyrus (detail); Egypt; ca. 13th–12th cent. bce. [Image courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum, London].

Figure 19. Tomb of Inherkau no. 359, Second chamber, South wall, "The great cat of Heliopolis" killing the enemy of the sun, Apophis.

Many daughters of Re could also play the protector role, including Bastet, Mut, Hathor, Sekhmet, and Serqet - ordinarly the scorpion goddess- “the daughter of Ra who protects her father” but always taking the form of a cat (Darnell 1997: 35-48).

Greek and Roman writers recorded a “ bizarre Egyptian belief that ichneumons (a type of mongoose) killed crocodiles by running down their throats and gnawing… through their bowels this may be a misunderstanding of the magical conflict between the sun god Re in the form of a mongoose or cat and Apophis in the form of a crocodile or snake.” (Eyre 1976: 103-114; King and Ichneumon n.d.; Wilson 1997; Pinch 2004: 127; PS 2). “In the afterlife, they had to evade the crocodiles of the four directions”, even though crocodiles were also good, represented by benevolent deities, even though they were dangerous (Eyre 1976: 103-114; King and Ichneumon n.d.; Wilson 1997; Pinch 2004: 127; PS 2)

“In the fight against Apep the eye of Re fought him under many names such as Bastet, Lady Of Terror, Wadjyt, the devouring Flame, The Glorious Eye (the eye that Re cut out to make his daughter Sekhmet* in the mythology), Wosret, and the Great One” (Darnell 1997; te Velde 1988; Pinch 2004: 130).

*One of many versions with a different Goddess as the main aspect name.

Each of the twelve gates of the underworld has a snake guardian — many are not evil, they’re either good or neutral. For example, when the solar barque and the corpse of Osiris (this time, not just Re) were protected by the coils of the Mehen snake, a kind of counter-Apophis (see, for example, Figure 38). As time itself was depicted as an endless snake that swallows up the hours. One of these images, the “Ouroboros” or the “tail-in-mouth” serpent, passed into other cultures as a symbol of infinity (see Figure 18)(Pinch 2004: 200).

Figure 20. The Mehen snake protected the ram-headed night sun in his boat. From an Underworld Book on the walls of a royal tomb. (Courtesy of Geraldine Pinch)

Figure 21. The sun child inside the Ouroboros snake is supported by the sky cow and the lions of yesterday and tomorrow. Vignette from the funerary papyrus of Herweben (British Museum)

Sokar, shown as a falcon-headed god — rather than the crocodile god he is usually shown as —, overcomes a chaos serpent in a cave guarded by the Aker sphinx in the New Kingdom Amduat (Book of the Underworld) painted (partly) in the tomb of Thutmose III at Thebes (Figure -)(Pinch 2004: 202).

Figure 22. Sokar protecting Re in tomb of Thutmose III (Courtesy of Nigel Strudwick).

“Atum and [Apep] have been interpreted by some egyptologist as positive and negative forces in chaos” (Zantac 1992: 169 -185; Mysliwiec 2001: 158-160 in Pinch 2004: 111; PS 1). Atum comes from a word meaning completeness or totality. When the Primeval Mound came into existence, Atum had a place to begin creation and give birth to the first two gendered deities, the father and the mother of all the gods (Zantac 1992: 169 -185; Mysliwiec 2001: 158-160; Pinch 2004; PS 1). While Atum is shown as a man with an erect penis generally, in the New Kingdom they were shown as a feminine counterpart (Zantac 1992: 169 -185; Mysliwiec 2001: 158-160; Pinch 2004; PS 1). The ultimate Divine and Royal ancestor who combined with Re in a later period (Zantac 1992: 169 -185; Mysliwiec 2001: 158-160; Pinch 2004: 111).

“Geb is accepted as ruler and has to rally his forces to defend Egypt against the “children of Apophis” (Pinch 2004: 77).

“The soul might experience life in the Field of Reeds, a paradise similar to Egypt, but this was not a permanent state. When the night sun passed on, darkness and death returned. The star-spirits were destroyed at dawn and reborn each night. Even the evil dead, the Enemies of Ra, continuously came back to life like Apophis so that they could be tortured and killed again. As the Western Souls, the justified dead formed part of the crew of the embattled Boat of Millions. They might be thought of as rowing or towing the sun boat or even defending it against the forces of chaos.”

(Pinch 2004: 93-94)

The picture associated with Book of the Dead spell 39 shows a dead person taking on Seth’s role of spearing the Apophis serpent. In death, everyone could be a cosmic hero in the perpetual struggle that was the central feature of Egyptian myth” (Pinch 2004: 93-94). Everyone could be Superman. (Figure).

Figure 23. Iron giant following Superman. Posted on Pinterest by TCB97/alessandrodacosta97

The perpetual battle between Seth and Apep is analogous with a single battle which took place in the Mythic past. Seth versus Yam, the insatiable sea, who is threatening to swallow the Earth (Pinch 2004: 193). The ending is missing in the only narrative version found, but several New Kingdom spells “claim the magician will overcome demons just as Seth once overcame the sea monster” (Pinch 2004: 193). This could be another being or perhaps another name for Apep, as it is taking on the same action that Apep did in myth and is sometimes depicted as a serpent in the water.

Part 2: Apophis in Stargate SG-1

Figure 24. Sceen-grab from Into the Serpent’s Lair part 1

Role and Characteristics:

Not counting the movie, the first “god” we are introduced to is Apophis. Coming through the cloaked Stargate with his guards at the beginning of episode one: “Children of the Gods”, he kidnaps a female member of Stargate personnel, making his eyes glow directly at General Hammond, making him think Re was back.

Figure 25. Screen grab from episode one Children of the Gods Part 1.

In the television series Stargate SG-1, the Goa'uld Apophis, played by Peter Williams, is depicted as a formidable and ancient alien parasite belonging to the Goa'uld race. For those who haven’t seen it, the Goa’uld are an alien race of parasitic beings that infiltrate and take control of human hosts by wrapping around their spinal cord and connecting directly to their brains (Episode 2: SG-1 1997). These Goa'uld are portrayed as god-like entities who enslave humanity by wielding advanced technology and posing as gods from ancient mythologies. Apophis, within this narrative, stands out as one of the most powerful, ruthless, and cunning of the Goa'uld System Lords, eventually commanding the greatest influence and fear across the galaxy before *spoilers*.

Like the ancient Egyptian Apep, the TV version is an antagonist with god-like power. However, instead of being a cosmic force of chaos that opposes Ra, Stargate SG-1’s Apophis adopts a more direct and personal approach to power. Apophis portrays himself as a god, demanding worship and adoration from his human subjects and the Goa’uld foot soldiers/incubator species called Jaffa, and he sees himself as a ruler over a vast empire. He is authoritarian, manipulative, and cruel, reflecting a more traditional villainous archetype. And best of all, he is such a drama queen, who is completely in love with and obsessed with Teal’c.

Figure 26. A group of Jaffa, ready for battle

Apophis in Stargate SG-1 retains the snake symbolism from the original myth. He is often depicted as an enormous serpent or as a snake-like Goa'uld parasite inside the body of his human host. This imagery connects the character to the original Apophis’s associations with serpents as symbols of destruction and chaos.

Figure 27. Goa'uld Symbiote by specs2

Cultural and Narrative Context:

Villainous Role: Apophis in Stargate SG-1 is primarily a villain. He represents a tyrannical god-king who seeks to dominate and enslave humanity. His quest for power is central to the narrative arc of the show, particularly in the first several seasons, where his conflict with the protagonists—SG-1, a military team investigating alien technology and ancient artifacts—forms the basis for many episodes.

Personality and Motivation: In contrast to the mythological Apophis, whose actions are driven by the cosmic need to destroy the sun and thus represent chaos in the universe, the Apophis of Stargate SG-1 is driven by personal ambition, revenge, and a desire to assert his dominance over other Goa'uld System Lords and humanity. He is portrayed as an egomaniac with delusions of grandeur, believing himself to be a living god and seeking to control the universe.

After he falls from his system lord status, his main goal is getting revenge on Teal’c. Especially after he’s brought back from the dead by Sokar and, with Sokar’s death in the same 2-part episode, Apophis “inherits” his massive army. And, slowly, he conquers his way back to his place in the system lords. Then he constantly focuses on Teal’c, ignoring and/or waving women off whenever he is brought before Apophis. Even brainwashing him to serve his “god” again.

The thematic shifts are shown in the original Apep represented a metaphysical concept of disorder and chaos, while the Stargate version is an alien conqueror with much more human traits—hubris, arrogance, and a desire for revenge. His conflict with Ra in the show is a non-starter because Ra is dead before the show stars.

Comparison and Contrast

Similarities:

Cosmic Opponents: Both versions of Apophis serve as a primary antagonist the order of the universe. In ancient Egyptian mythology, Apep is Re’s eternal enemy and basically every god/goddess helps him in some version of the myth. In Stargate SG-1, Apophis was also a rival to Ra (who was depicted as another Goa'uld system lord), and his struggle with all the other system lords later in the series is a battle for dominance, both politically and militarily, within the Goa'uld Empire. When he takes over so many armies, Apophis does throw the rest of the universe of system lords into total chaos and they have to even go to the SGC and the Asgard for help defeating him.

Serpent Imagery: Both the mythological Apophis and the Stargate SG-1 Apophis are associated with serpents. The snake symbolism is an essential aspect of Apophis’s identity in both contexts, reflecting his role as a bringer of destruction and chaos.

Villainous Traits: In both depictions, Apophis is portrayed as malevolent, manipulative, and destructive. His primary goal in both the mythological and modern contexts is to bring disorder—whether through attempting to swallow the sun or through plotting to conquer the universe and enslave humanity.

Differences:

There was never a cult for Apep, priest made models or pictures of Apep which they would then curse and then destroy the likeness by stabbing, trampling, or burning (Borhouts 1973: 114-150 ; Hornug 1982 103-113).

Metaphysical vs. Personal Motivations: The mythological Apep is a metaphysical force of chaos whose motivations are tied to cosmic balance, representing the natural opposition to Re and the forces of order. In contrast, Stargate SG-1’s Apophis is motivated by personal ambitions, such as revenge, power, and control, which are more in line with a traditional villainous archetype. He is more a tyrant and conqueror than an embodiment of cosmic disorder.

Role in the Story: Apep in Egyptian mythology is an impersonal, cosmic entity whose role is abstract and tied to religious and cultural beliefs about the universe, the afterlife, and the king’s role in maintaining order. In Stargate SG-1, Apophis is a central antagonist whose presence drives the plot in the early seasons of the show. His actions are more directly linked to the characters’ goals and challenges.

Human Interaction: The Egyptian Apophis is primarily a divine force that interacts with gods (Ra, Set, Thoth, etc.) and the cosmos, while in Stargate SG-1, Apophis is a tangible character who interacts with humans, particularly SG-1 and the military forces of Earth. His character is anthropomorphized, giving him personal goals and motivations, which is a departure from the more abstract, mythological figure.

Role of Ra: In Egyptian mythology, Ra is the ultimate solar god, and Apophis is his eternal enemy. In Stargate SG-1, Ra is also a Goa'uld System Lord, but is dead before the series starts after he was nuked in the movie. This is almost an inversion of roles contrasts with the original myth, where Apophis is always the challenger, never the ruler and Re is the one that never died.

Apophis in Egyptian Funerary Tradition

In the "Book of the Dead" and "Coffin Texts," Apophis' defeat by Ra symbolizes the soul’s journey overcoming darkness and chaos to reach eternal life. Fear of Apophis’ chaos reaches tombs, where inscriptions and amulets protect the dead, highlighting his role in afterlife beliefs.

Apophis' Influence on Egyptian Cultural Traditions

Apophis' mythology is tied to maat, Egypt's divine order of universe and justice. The daily Ra-Apophis battle symbolizes the clash of ma’at (order) and isfet (chaos). Pharaohs, seen as living gods and embodiments of ma’at, and thus had the role as Re’s earthly agents maintaining order. Apophis symbolizes existential threats to this divine order, like rebellion and societal collapse. Apophis' defeat symbolizes both theology and culture. Rituals like sacred readings and gestures reinforce social order, ensuring safety and Egypt's stability.

Evolution of Apophis’ Myth in Literature and Art:

Over time, Apophis changes from a simple enemy of Ra to a complex symbol of chaos, death, and danger. The stories about his fight with Ra become more detailed, describing his shapes and powers clearly. New Kingdom art depicts Apophis as a huge, menacing snake in cosmic scenes, highlighting his global threat. Temple carvings and tomb paintings portray him as an enduring enemy in Egyptian spiritual and royal symbolism.

Conclusion:

The Apophis of Stargate SG-1 takes significant inspiration from the ancient Egyptian mythological figure but reinterprets him for a modern, science fiction context. While the core elements of chaos, serpentine imagery, and opposition to all of the are retained, the motivations, personality, and narrative function of Apophis are heavily adapted to fit the show’s genre, character dynamics, and themes of personal power struggles. The mythological Apep represents a cosmic force of disorder, while the Stargate version is a more traditional, power-hungry villain driven by personal revenge and ambition. Both versions, however, continue to serve as symbols of chaos and a challenge to order—whether in the ancient Egyptian cosmos or the fictional universe of Stargate SG-1. Despite the changes in political and cultural contexts, the mythology of Apophis remains relatively constant in its core symbolic meanings. His role as the enemy of Ra and personification of chaos reinforces the enduring Egyptian emphasis on cosmic order and the fragility of life. Though Apophis eventually fades from active religious practice by the end of the Ptolemaic period, the themes associated with his mythology—order versus chaos, life versus death—persist in various forms, echoing throughout Egyptian history and beyond.

Apophis' mythology is closely tied to the ancient Egyptian concepts of *maat* (order) and *isfet* (chaos), with Apophis symbolizing the forces of disorder. Apophis' connection to the underworld and his threat to the dead shows how Egyptian views on death and the afterlife were intertwined with their cosmic understanding. The connection between the king and the divine order is often reinforced through Apophis' role as a threat to Ra’s rule and the stability of Egypt. Over time, Apophis' character absorbed elements from foreign cultures and religious practices, demonstrating the adaptability of Egyptian myth in response to changing political landscapes.

*SPOILER: He died because the Replicators taking over his ship and they crashed it accidently into the Pacific Ocean during an uncontrolled re-entry.

Random Extra:

99942 Apophis (2004 MN4) is a near-Earth asteroid about 450 by 170 meters in size (Brozović et al. 2018). In December 2004, scientists briefly worried it might hit Earth on April 13, 2029, with a 2.7% chance. Later observations showed it won’t hit Earth in 2029. However, there was a small chance it could pass through a tiny gravitational "keyhole" during that close approach, which might cause a collision in 2036 (Noland 2006, Giorgini et al. 2007). "Predicting the Earth encounters of (99942) Apophis" (PDF). Icarus. 193: 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.09.012.). This risk kept it at Level 1 on the Torino hazard scale until August 2006, when the chance was found to be very small and the rating dropped to Level 0. By 2008, the keyhole was confirmed to be less than 1 km wide. At its peak in December 2004, Apophis reached Level 4, the highest ever on the Torino scale (Yeomans et al. 2004).

When first discovered, the object received the provisional designation 2004 MN4, and early news and scientific articles naturally referred to it by that name. Once its orbit was sufficiently well calculated, it received the permanent number 99942 (on June 24, 2005). Receiving a permanent number made it eligible for naming by its discoverers, and they chose the name "Apophis" on July 19, 2005. Tholen and Tucker, two of the co-discoverers of the asteroid, are reportedly fans of the television series Stargate SG-1. One of the show's persistent villains is an alien named Apophis. He is one of the principal threats to the existence of civilization on Earth through the first few seasons, thus likely why the asteroid was named after him. In the fictional world of the show, the alien's backstory was that he had lived on Earth during ancient times and had posed as a god, thereby giving rise to the myth of the Egyptian god of the same name (Cook 2005).

The mythological creature Apophis is pronounced with the accent on the first syllable (/ˈæpəfɪs/).[c] In contrast, the asteroid's name is generally accented on the second syllable (/əˈpoʊfɪs/,[33] or /əˈpɒfɪs/ as the name was pronounced in the TV series).[34]

Citations:

Allen, James P[eter]. (2010). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, 2nd edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, page 102.

Alchin, Linda. n.d. "The Uraeus Symbol". Egyptian Gods. Siteseen Ltd, https://www.landofpyramids.org/uraeus.htm

Apophis: every ancient Egyptian’s greatest fear after death. (n.d.). History Skills. https://www.historyskills.com/classroom/ancient-history/apophis/.

Borghouts, J. F. (1973). The Evil Eye of Apopis. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 59(1), 114-150. https://doi.org/10.1177/030751337305900115.

Brozović, M.; Benner, L. A. M.; McMichael, J. G.; Giorgini, J. D.; et al. (January 15, 2018). "Goldstone and Arecibo radar observations of (99942) Apophis in 2012–2013" (PDF). Icarus. 300: 115–128. Bibcode:2018Icar..300..115B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2017.08.032. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

Bunson, Margaret R. 2002. Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Rev. ed. Facts On File, Inc. Printed in the US.

Cooke, B. (August 18, 2005). "Asteroid Apophis set for a makeover". Astronomy Magazine. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

Darnell, John Coleman (1997). "The Apotropaic Goddess in the Eye". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 24: 35–48. JSTOR 25152728.

Delvaux, L. and E. Warmenbol (eds.). (1991). Les Divins Chats D’Égypte. Leuven, Belgium.

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2025, February 24). “Apopis”. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Apopis-Egyptian-god.

Eyre, C. (1976). “Fate, Crocodiles, and the Judgement of the Dead. Some Mythological Allusions in Egyptian Literature.” Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 4 : 103–114.

Faulkner, Raymond Oliver. (1962). A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, Oxford: Griffith Institute.

Fleming, Fergus and Lothian, Alan (1997). The Way to Eternity: Egyptian myth. Amsterdam: Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-7054-3503-1.

Giorgini, Jon; et al. (October 4, 2007). "Predicting the Earth encounters of (99942) Apophis" (PDF). Icarus. 193: 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.09.012.

Hill, J. (2010). Apep (Apophis). Ancient Egypt Online Ancient Egyptian history and art. https://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/apep/.

Hornung, E. (1982). The triumph of magic: The Sun God’s victory over Apophis. The Valley of the Kings: Horizon of Eternity, 103-13.

King and Ichneumon, 664–332 B.C.E.. Bronze, 5 x 4 1/2 x 2 1/2 in. (12.7 x 11.4 x 6.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 76.105.2. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

Littleton, C. S. (2002). Mythology: the illustrated anthology of world myth & storytelling. Duncan Baird.

Loprieno, Antonio (1995). Ancient Egyptian: A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, page 71.

Lurker, M. (1978). A dictionary of gods and goddesses. Devils and Demons (Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2015).

Malek, J. (1993).The Cat in Ancient Egypt. London.

McCormick, K. D. (n.d.). Apophis | Dragons of Fame | The Circle of the Dragon. https://www.blackdrago.com/fame/apep.htm#footnotes2

Mysliwiec, K. “Atum.” In The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egypt I, edited by D. Redford. Oxford and New York: 2001, 158–160.

Noland, David. (November 7, 2006). "5 Plans to Head Off the Apophis Killer Asteroid". Popular Mechanics.

Pinch, Geraldine (2004). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 106.

Rose, C. (2001). Giants Monsters and Dragons: An Encyclopedia Of Folklore Legend And Myth. WW Norton & Company.

Rubin, Aaron D. (2004) “An Outline of Comparative Egypto-Semitic Morphology” in Egyptian and Semito-Hamitic (Afro-Asiatic) studies: in memoriam W. Vycichl, page 481.

Scarab with ichneumon (mongoose) | Third Intermediate Period | The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (n.d.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/553404.

Sutherland, A. (2001). Never-Ending Battles Between God Ra And Indestructible Apophis In Ancient Egyptian Beliefs. Ancient Pages. https://www.ancientpages.com/2021/05/20/never-ending-battles-between-god-ra-and-indestructible-apophis-in-ancient-egyptian-beliefs/.

te Velde, H. (1988) “Mut, the Eye of Re.” Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur Beiheft 3: 395–403.

Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson Inc., New York, New York. https://archive.org/details/TheCompleteGodsAndGoddessesOfAncientEgypt/The%20Complete%20Gods%20and%20Goddesses%20of%20Ancient%20Egypt/page/n3/mode/2up

Wilson, P. (1997).“Slaughtering the Crocodile at Edfu and Dendera.” In The Temple in Ancient Egypt, edited by S. Quirke. London: 179–203.

Wolterman, C. (2002). in Jaarbericht van Ex Oriente Lux, Leiden Nr.37 .

Yeomans, D.; Chesley, S.; Chodas, P. (December 23, 2004). "Near-Earth Asteroid 2004 MN4 Reaches Highest Score To Date On Hazard Scale". NASA/JPL CNEOS.

Zandee, J. “The Birth-giving Creator-god in Ancient Egypt.” In Studies in Pharaonic Religion and Society, edited by A. B. Lloyd. London: 1992, 169–185.

Primary sources:

1 - PT 527, 600, 606; CT 76, 80; BD 17, 175; Ad; BOG Hours 2, 3, 7; HMP; Magical statue texts; MT; BRP

2 - BD 31–32; DP; BOE; HMP; Herodotus H II.68–69; Diodorus I.34, 89; Strabo G XVII.44, 47; BOF

3 - CT 76, 80, 1000; BD 17; Crossword hymn; BHC; Mut ritual; BRP; Sekhmet litany; Kom Ombo texts; EofS

4 - PT 295, 297–8, 519; CT 335, 470; BD 17, 125; LofR; Mut ritual; EofS; Ankhsheshonq.

![Figure 11. The New York Public Library. (1841). Pantheon. Aphophis [Apophis]. Public Domain. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/80055c90-c6cf-012f-93d2-58d385a7bc34](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6598c864ea0f89700c0e4e59/1751406658606-POLZXWAOGY30PZVXENZ1/horus-defeating-apep-the-chaos-serpent-using-a-spear-one-figure-appears-human-while-the-other-has-a-falcon-head-symbolizing-divine-power-overcoming-evil-in-ancient-egyptian-mythology.jpg)