Sokar - The Hidden Onion

Introduction

Imagine a world where the sun doesn't just set; it dies. As the solar barque of Re descends into the earth, it passes through gates guarded by serpents until it reaches the most desolate region of all: Ro-Setau, the Land of the Passages.

Unlike the lush fields of the afterlife you might expect, this place is a vast, silent desert of sand and darkness. There is no river here. The sun god’s boat must be transformed into a serpent-headed sledge just to be dragged across the dunes. And there, in the pitch-black heart of this wasteland, sits a god who is as much a part of the earth as the rocks themselves.

He is Sokar.

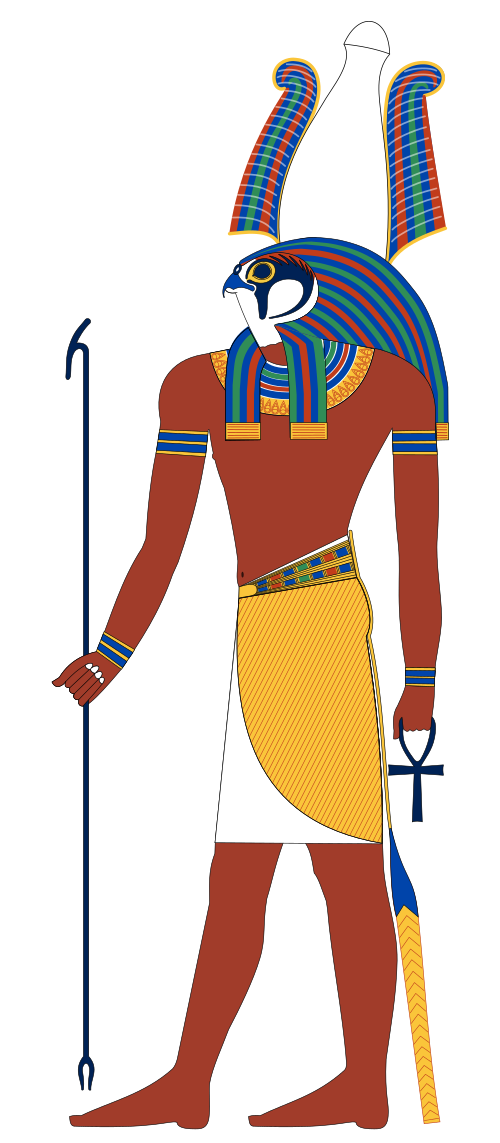

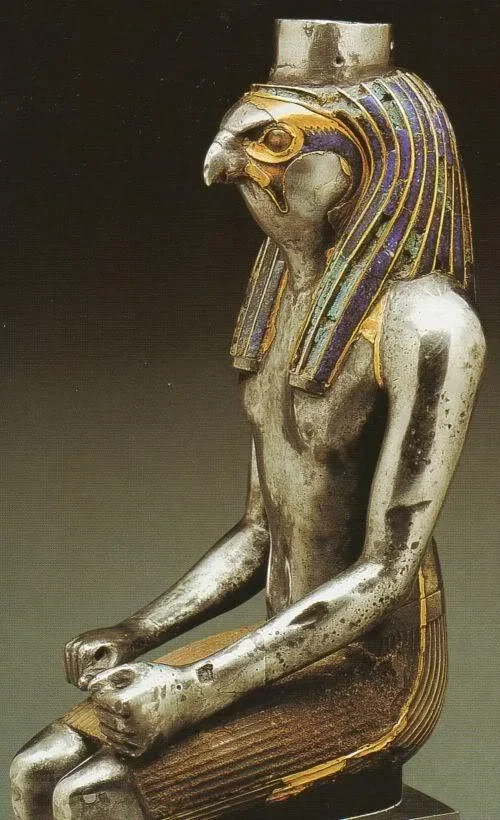

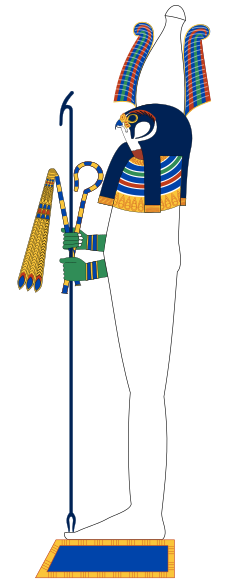

He doesn’t look like the golden kings of the living world. In artwork, he is often a mummified man with the head of a falcon, his skin sometimes painted a ghostly white or a deep, earthy green. He sits upon a throne that is actually a burial mound, a 'Hidden Mound' that represents the very first piece of land to rise from the chaos of creation.

Figure 1. The hark-/falcon-headed god Sokar, holding an ankh, the was-sceptre, wearing the white feather crown of Osiris.

But Sokar isn't just a guardian of the dead; he is the master of transformation. He is the patron of the goldsmiths who hammered out the funeral masks of pharaohs. Just as a craftsman takes raw, cold metal and turns it into a shimmering masterpiece, Sokar takes the cold, silent body of the deceased and prepares it for a fiery rebirth.

When you look at his image on a tomb wall or a ceremonial Henu barque, you aren't just looking at a god of death. You’re looking at the silent, patient power of the earth itself—the moment where the end of the journey becomes the beginning of something new.

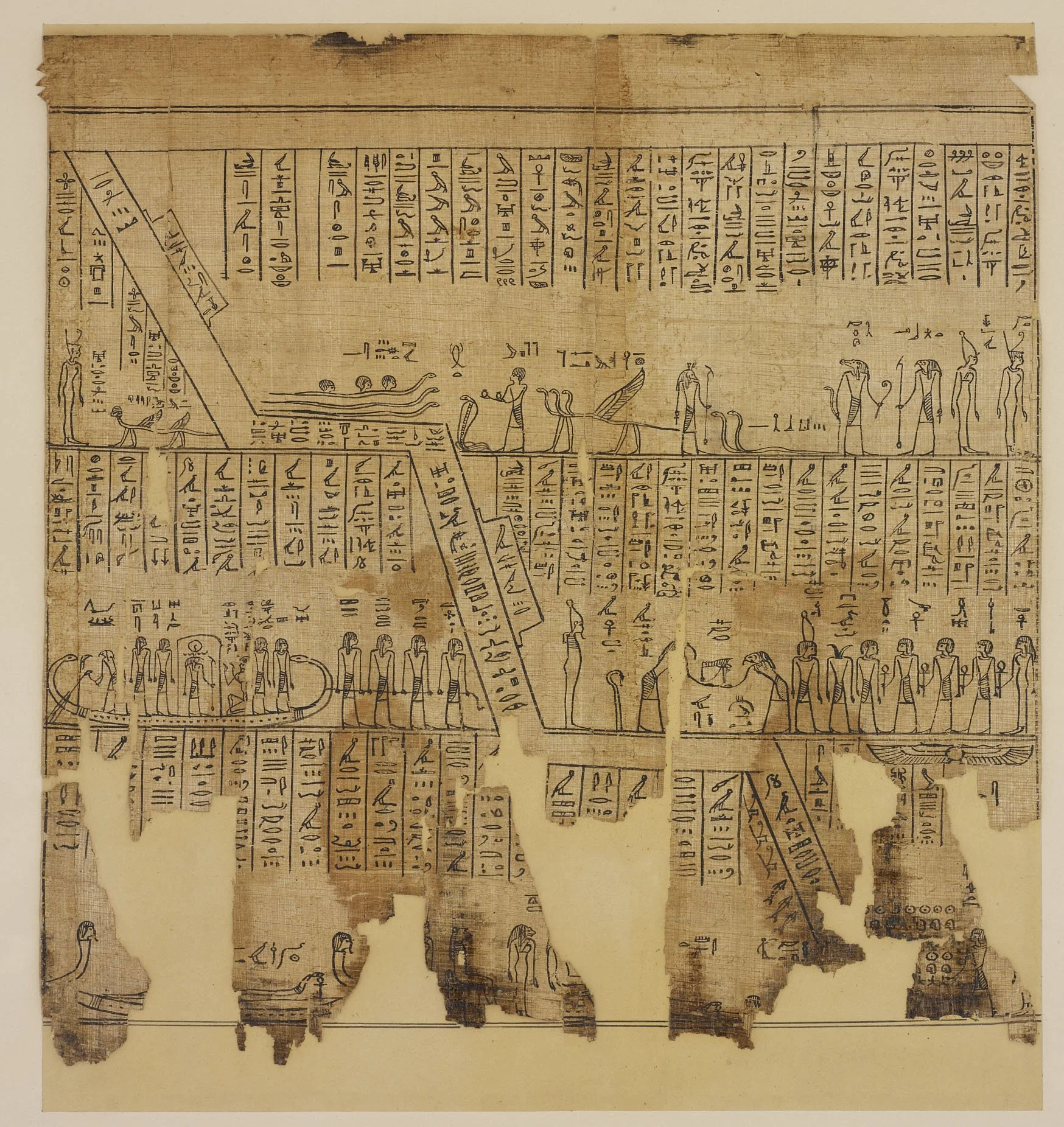

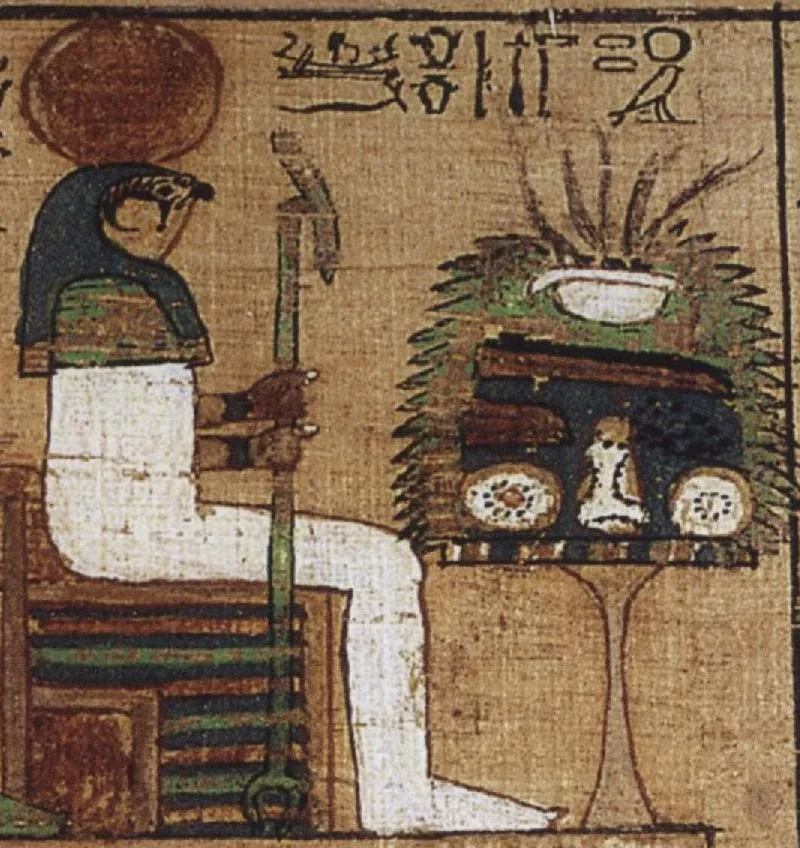

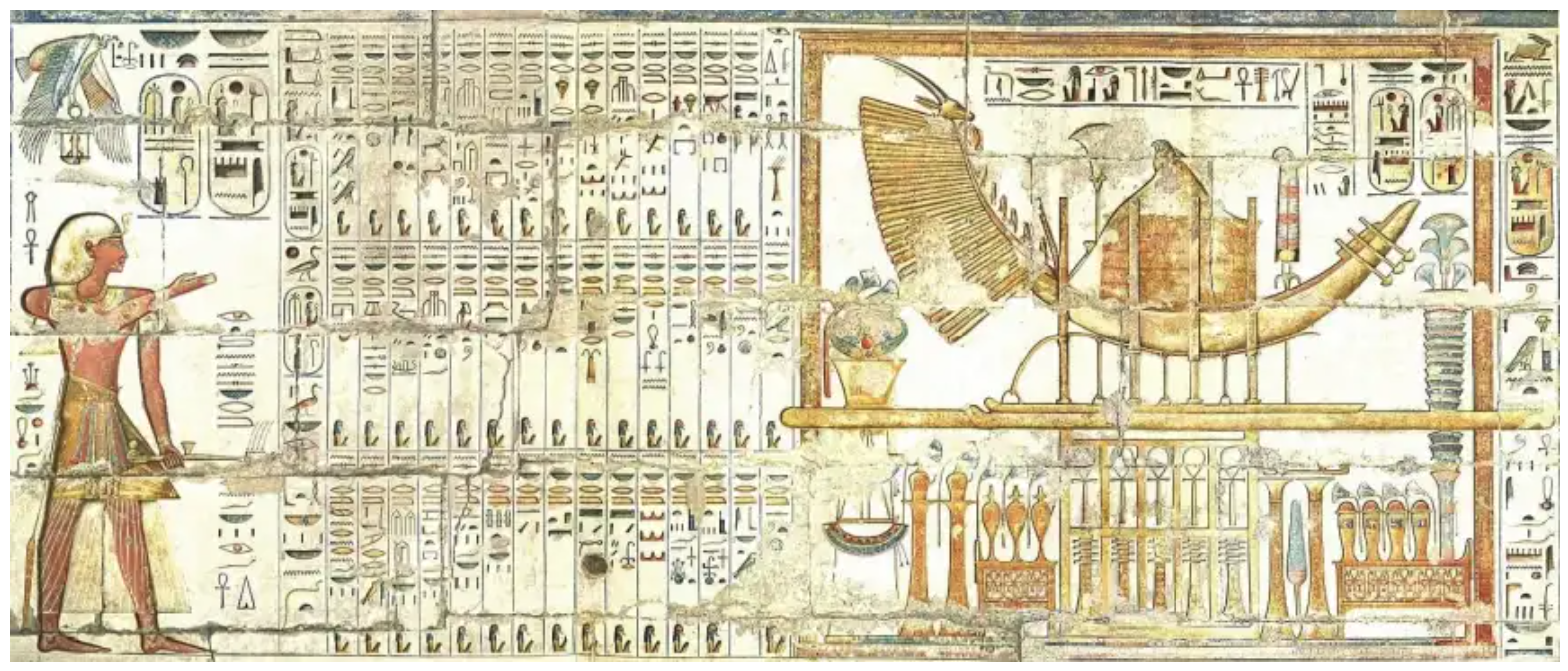

Figure 2. Book of the Amduat

I’ll be tracing the evolution of Sokar’s representation in art and its changing iconography over time. By examining various art historical sources, we can understand how the depiction of Sokar transformed in relation to cultural and historical shifts.

As opposed to how he’s depicted in Stargate, he wasn’t a devil in any way; he was another god, partly of the underworld, but in the super-helpful way most Egyptian gods actually were.

Context Overview

Sokar also spelt Seker, and in Greek, Sokaris or Socharis, was a funerary god of the Memphite necropolis in the 1st Nome, also worshipped in Saqqara, and was known as a patron of the living, as well as a god of the resurrected dead (Hart 2005: 203). Sokar, he who is on his sand, was also worshipped in Giza as the lord of Rosetau, which was the entrance to the realm of the dead, and elsewhere. Sokar was known by the epithet “he of Rosetau”. This refers to the area around the Giza pyramids, as well as to any necropolis and to the entrance to the underworld. He is also known as the “lord of the mysterious region” (the underworld) and the “great god with his two wings opened”, referring to his origins as a hawk or falcon deity.

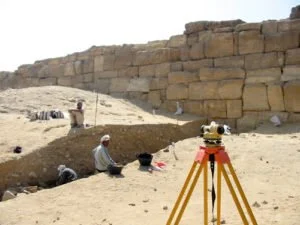

Figure 3. Wall of the Crow at the Giza necropolis.

Although the meaning of his name remains uncertain, the Egyptians in the Pyramid Texts linked his name to the anguished cry of Osiris to Isis, ‘Sy-k-ri’, “hurry to me”, or possibly ‘skr’ could be a shortened version of ‘sokar-n-re’ meaning "cleaning the mouth of Re". ‘Skr’ could also mean "adorn one", "decorate one", or even possibly "sail" (Hart 2005, Sokar 2019, EFT 2025). In the later periods, in the underworld, Sokar is strongly linked with two other gods, Ptah, the Creator god and chief god of Memphis, and Osiris, the god of the dead. This connection was expressed as the triple god Ptah-Sokar-Osiris (which I’ll discuss in more detail later) (Hart 2005: 202).

As a standalone, he is commonly depicted as a hawk or falcon, or as a man with a hawk or falcon head, sometimes mummified, and often set within intricate scenes related to funerary rites. He is also, in some accounts, a solar deity, celebrated in the Temple of Sokar in Memphis. His iconography dates to the early dynastic period, with representations found in artefacts such as the stelae and tomb murals from the Old Kingdom. The earliest evidence of Sokar appears in funerary contexts, emphasising his role as a protector of the deceased during their journey in the afterlife (Vanhulle, 2025).

Parentage & Family

Sokar was an interesting case study of beings not directly connected to other gods. In ancient Egyptian mythology, the god Sokar is generally considered a deity with no direct or formalised parentage. Unlike many other gods who belong to established family trees, such as the Ennead, Sokar is a unique figure who likely originated as a local hawk totem in the Memphite necropolis before becoming a universal funerary deity.

Scholars find him fascinating because he lacks a formal biological lineage, with ancient texts even calling him both “father and mother” to suggest he is a self-made, primordial force. While the Pyramid Texts include a play on words linking his name to the cry “hurry to me” (Sy-k-ri), it’s just clever etymology rather than a birth story. Instead of parents, he is defined by his “brothers” through syncretism, eventually merging with Ptah and Osiris to represent the complete cycle of life, death, and rebirth. His family life is just as unconventional: he has no clear children—though Redoudja is occasionally mentioned as a son—and while he is sometimes paired with Nephthys, he is more officially linked to Sekhmet via his connection to Ptah.

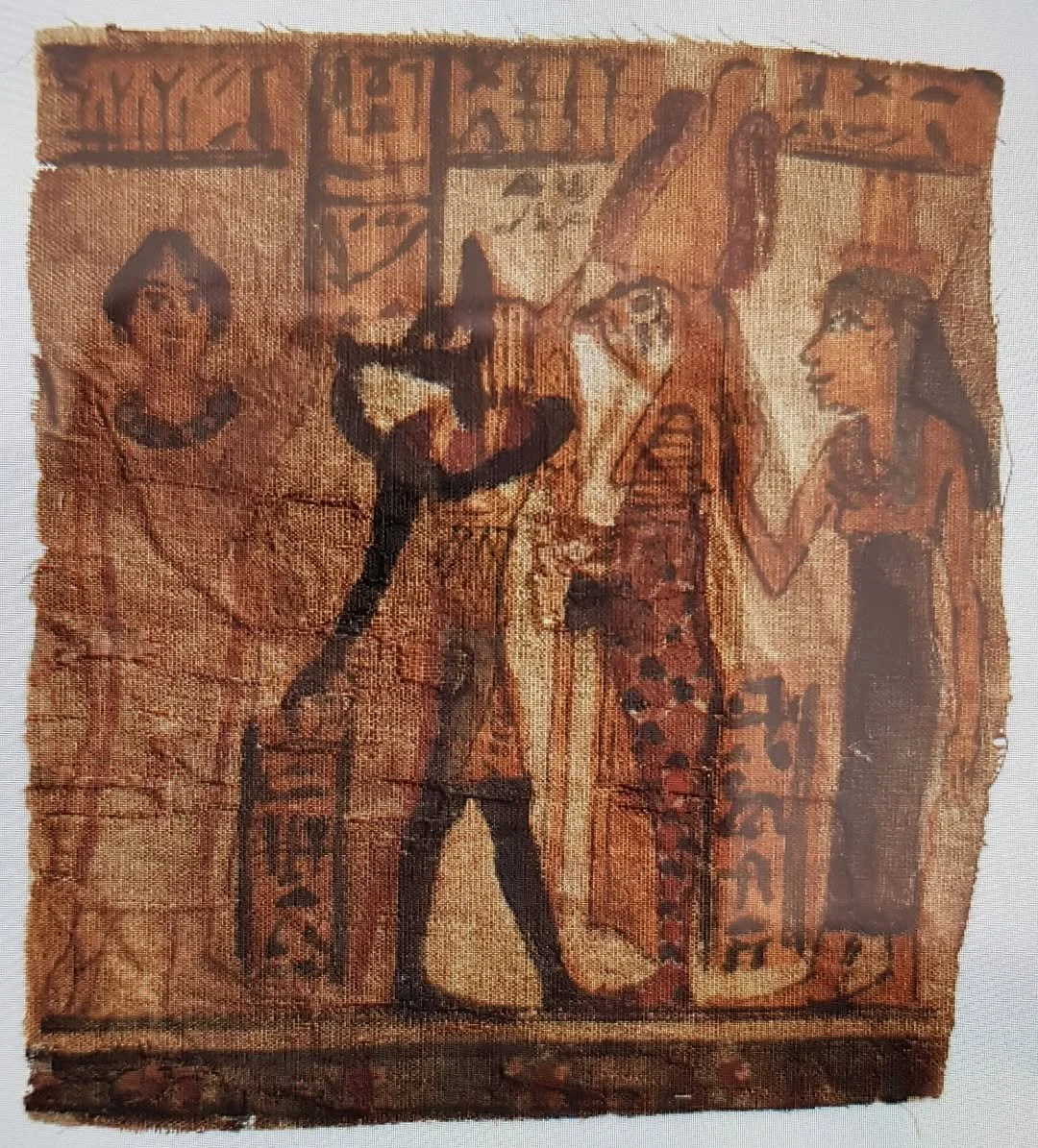

Figures 4 & 5. Section of a shroud

A section of a shroud. The painted scene depicts a dead Tashay, who is presented by Anubis to Sokar-Osirus attended by goddess Nephthys. Dates: 140 -160 CE, Period: Graeco-Roman Period. Provenance: Egypt, Material: textile/fibres (linen). Located at The Egypt Centre, Swansea University, Swansea, UK (Griffiths 1982: 228-252).

Early Representations and Symbolism

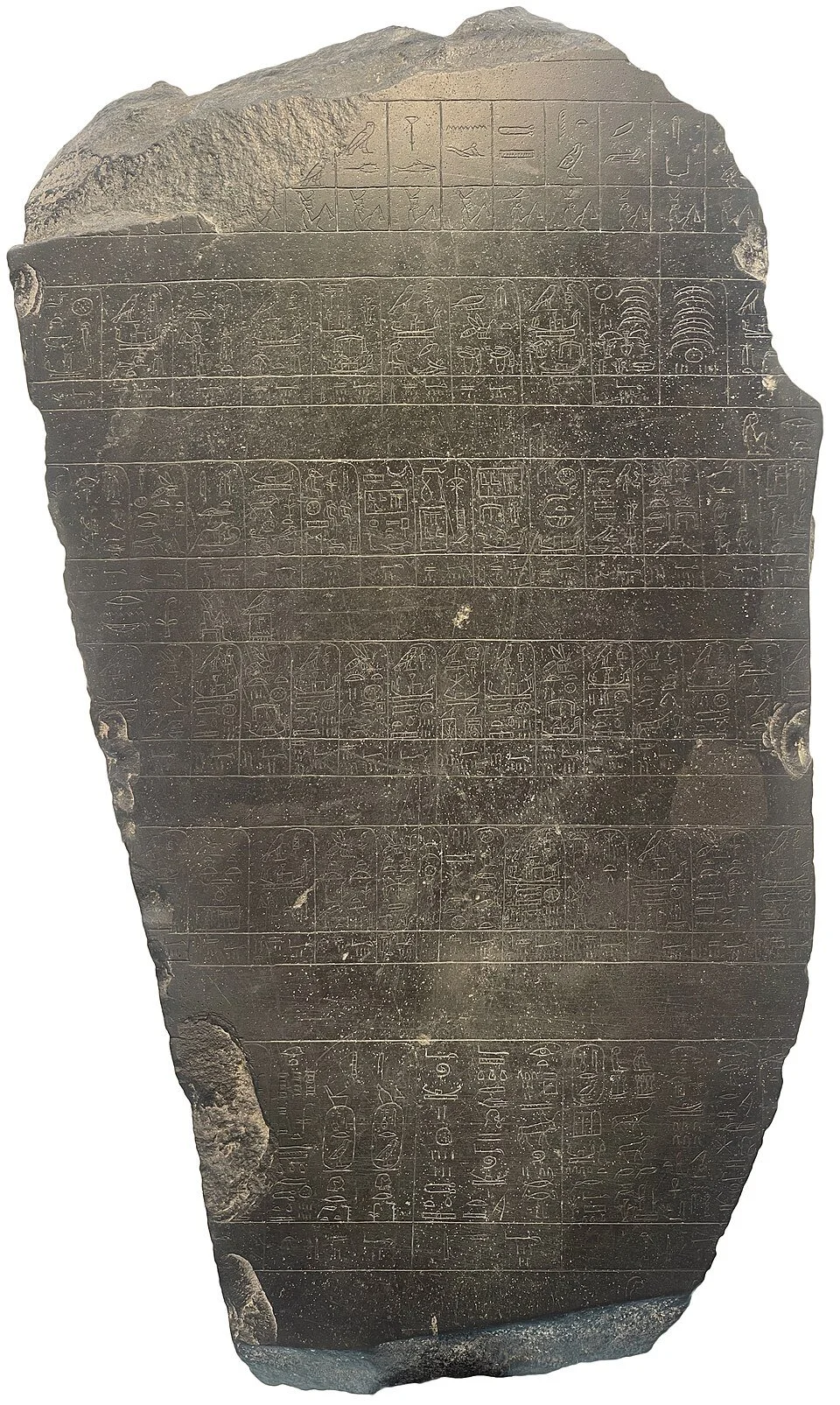

The earliest known references to a ceremony called 'going round the walls' (phr hi inbw) appear on the Palermo Stone. The Palermo Stone is one of seven surviving fragments of a stele known as the Royal Annals of the Old Kingdom of Ancient Egypt. The stele listed the kings of Egypt from the First Dynasty (c. 3150–2890 BCE) through to the early part of the Fifth Dynasty (c. 2498–2345 BCE) with recorded significant events in each year of their reigns, including indudation periods, measurements of the height of Nile flood, and details of festivals, taxation, sculpture, buildings, and warfare (Shaw 2003).

Figure 6. Palermo Stone. Royal Annals of Egypt (Old Kingdom). Museo archeologico regionale Antonino Salinas, inv.no. 1028.

One hypothesis is that the stone was carved during the Fifth Dynasty (c. 2400 BCE), although it has also been suggested that it was carved over time (Dodson 2004). This latter idea makes more sense to me, as who would remember Nile height measurements from hundreds of years earlier? Although the original location and context of the Palermo Stone are unknown, the fragments are held at the Regional Archaeological Museum Antonio Salinas in Palermo, Italy (from which it derives its name). There are five fragments of the Royal Annals in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, and one small fragment is in the Petrie Museum of University College London, forming part of the collection of the archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie (Schirò 2021). The references were written consistently occur during an accession year, as hundreds of years of kings and dynasties were carved onto the stone. By the way, this list of kings also includes the hieroglyphic names of Predynastic king names on one side (Helck 1956).

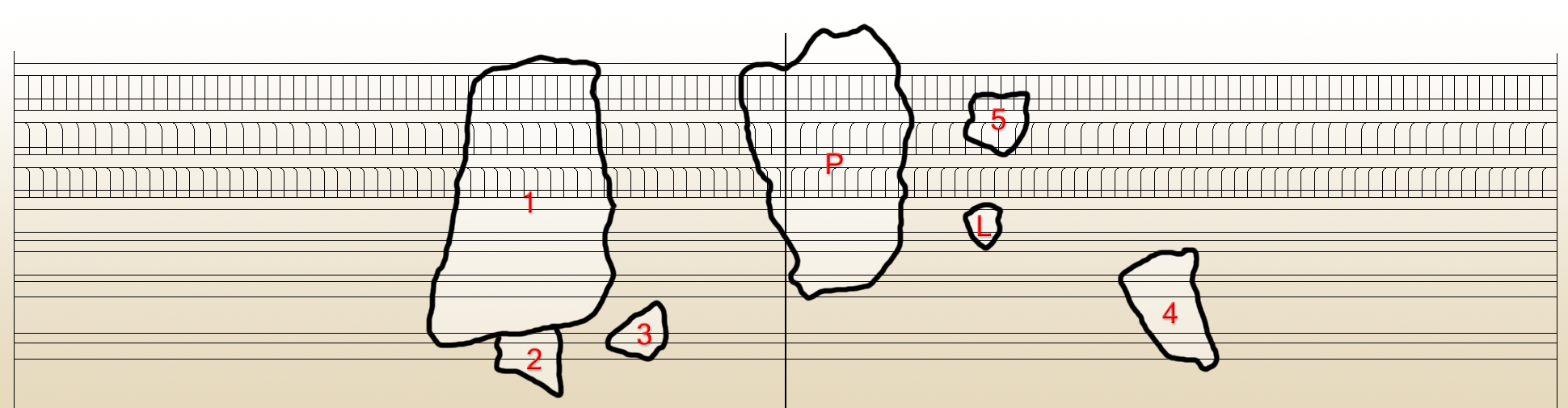

Figure 7. The Royal Annals of Egypt, showing a suggested reconstruction of the stele and the positions of the seven surviving fragments. P is the Palermo Stone, nos. 1-5 are the Cairo fragments, and L is the London fragment.

Focusing on the festival rituals, there is no clear evidence directly linking the Palermo Stone festivals to the celebration of the Festival of Sokar. However, the recording of festival rituals on stone was common, so I wouldn’t be surprised if a mention of some part of the Sokar festival appeared somewhere on the tablet. Another type of entry is more specific and has been interpreted as the 'Festival of Sokar', possibly as part of the specific years when Nynetjer of the 2nd dynasty participated in Sokar-related feasts alongside other gods and royal activities every six years (Wilkinson 2005: 260). This interpretation was widely accepted until recent times, when it came into question, but I’m not sure what the right answer is. But it makes more sense after adding in a smaller fragment of the annals, the Cairo Stone, which may record further events belonging to Nynetjer's later reign: another festival of Sokar in his 24th year on the throne, although like the other fragments, the dating in uncertain (Wilkinson 1999: 72, Schott 1950: 59–67, Kahl 2012: 107).

Early images of Sokar often connect him to life after death, highlighting his association with agricultural fertility, as seen in Egyptian art featuring vines and farming scenes. Throughout Egyptian history, his symbols frequently appear alongside daily life and farming activities. However, it's important to consult reliable sources to support these ideas, as current references don't fully substantiate them (Pomatto et al., 2022). This early artwork depicts Sokar as a symbol of renewal and protection. Some of the earliest images of Sokar show him seated in a silver boat called the Henu, dated to 3100 BCE - 2686 BCE, during the Early Dynastic Period (Shmoop Editorial Team 2008).

Sceptre - Symbol

Like many other gods, he was often depicted with a Was-sceptre (Hart 2005). In this case, though, it plays into Sokar’s duties. The sceptre not only symbolises power, but it’s also the tool of the extremely important ritual that took place during the mummification process, the Opening of the Mouth. [I looked into it for my master’s thesis (chapter 3).]

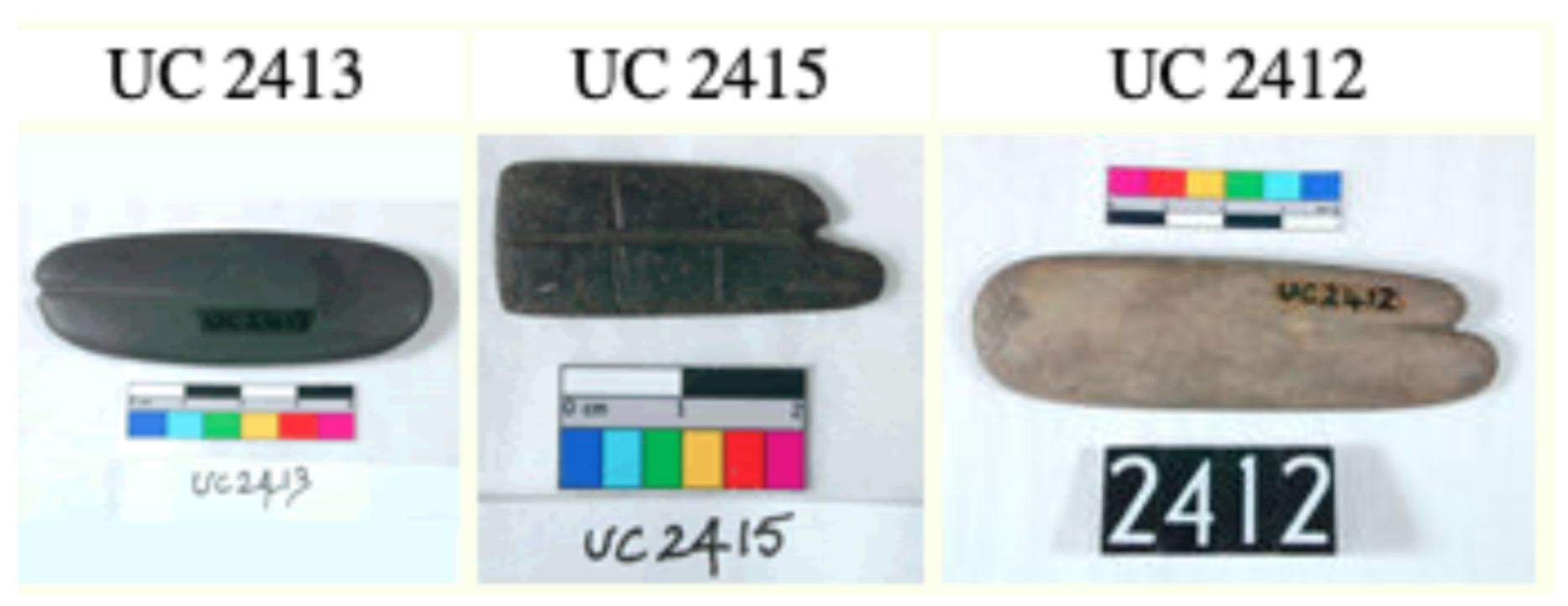

The process is not only depicted on the walls of tombs, but miniature versions were also buried with the deceased as amulets inside the mummy’s wrappings from the Old Kingdom into the Roman Period (Assmann, 2005; Roth, 1992; Roth, 1993). They were often made of dark materials, including glass and gilt, and generally took the shape of two fingers (Figure 8 - UC2413, UC2415, & UC 2412) to invoke the ritualistic meaning of the opening of the mouth by Horus, as described on a tomb wall:

Words spoken by the sem-priest, lector-priest, imy-is priest standing around the person referred to as ‘N’ were:

my father, my father, my father, my father

Oh N! your mouth is ... (?): I have balanced your mouth and bones for you

N! I have opened your mouth for you

N! I open your mouth for you with the nua-blade

I have opened your mouth for you with the nua-blade,

the meskhetyu-blade of iron, that opens the mouths of the gods

Horus is the opener of the mouth of N, Horus; Horus has opened the mouth of N

Horus has opened the mouth of N with that with which he opened the mouth of his father, with which he opened the mouth of Osiris

with the iron that came from Seth, the meskhetyu-blade of iron

with which the mouths of the gods are opened - may you open the mouth of N with it

so that he may walk and speak with his body before the great Nine Gods in the great mansion of the official that is in Iunu

and so that he may take up your White Crown there before Horus lord of the nobility

(Translation done by the University College London, 2003).

Paintings guided the journey into the afterlife, explaining origins and purpose. Horus had to open Osiris’ mouth before mummification so he could speak prayers in the afterlife (Assmann & Lorton, 2005). This ritual was for preserving knowledge after death, as the dead answered the gods' questions during the heart-weighing ceremony. If they failed to answer as expected, Amut would devour them, ending their souls (Egyptian Book of the Dead, in Assmann & Lorton, 2005). Though the god changed from Horus to Sokar over the millennia, the opening-of-the-mouth ritual symbolises the creation of a perfect afterlife. Like other burial amulets, it has a metaphysical connection: writings, paintings, and prayers on tombs become real in the afterlife. Wishes, spoken or written, are represented by the was-sceptre, enabling the deceased to continue prayers and live forever in a self-created world, made possible by knowledge and speech.

Figure 8. Was-sceptre adzes shaped like fingers for the opening of the mouth ceremony (Roth 1993).

Changing Through Time

In Artistic Representation

Originally venerated as a totem, Sokar was later regarded as a personified hawk or falcon. During the Old Kingdom (c. 2686-2613 BCE), he appears in the earliest versions of the Pyramid Texts as the “creator of royal bones,” and the Book of the Dead says that he fashions a “foot basin of silver,” the material of the god’s bones. He was typically depicted seated on a throne, holding the Was sceptre and the Ankh symbol for life.

As Egyptian culture evolved, so did the artistic representations of Sokar. In the Middle Kingdom, Sokar’s imagery changed, increasingly linked to the Osirian cycle, resulting in artwork that highlighted themes of resurrection and rebirth. Tomb paintings from this period grew more detailed, showcasing not only falcon symbols but also scenes of the funerary rites associated with Sokar (Vanhulle, 2025). At Abydos, dating from 2055 BCE at the start of the Middle Kingdom, a dedicated chamber for Sokar was part of the large Osiris temple. Wall carvings depict a unique festival celebrating Sokar before the festival of Osiris.

During this period, Sokar was often combined with Ptah to form a composite deity called Ptah-Sokar. This figure symbolised the soil and its ability to create and sustain life. Since Ptah was regarded as the protector of artisans, because of his skills in metallurgy and his regenerative powers, Sokar became explicitly associated with protecting goldsmiths, even though he had previously been more closely connected to silver. Some parts of the extensive Pyramid Texts describe Sokar helping the king undergo rebirth and transferring divine royal powers to the king's son and heir. Sokar also clearly played a role in the body's transformation after death and in the Opening of the Mouth ritual. This ceremony plays a vital role in restoring a person’s senses and vitality in the afterlife. Without it, the spirit could not eat, drink, or move, underscoring Sokar’s essential role in the afterlife (EFT 2025).

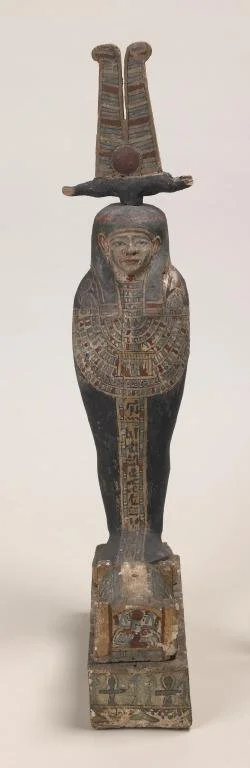

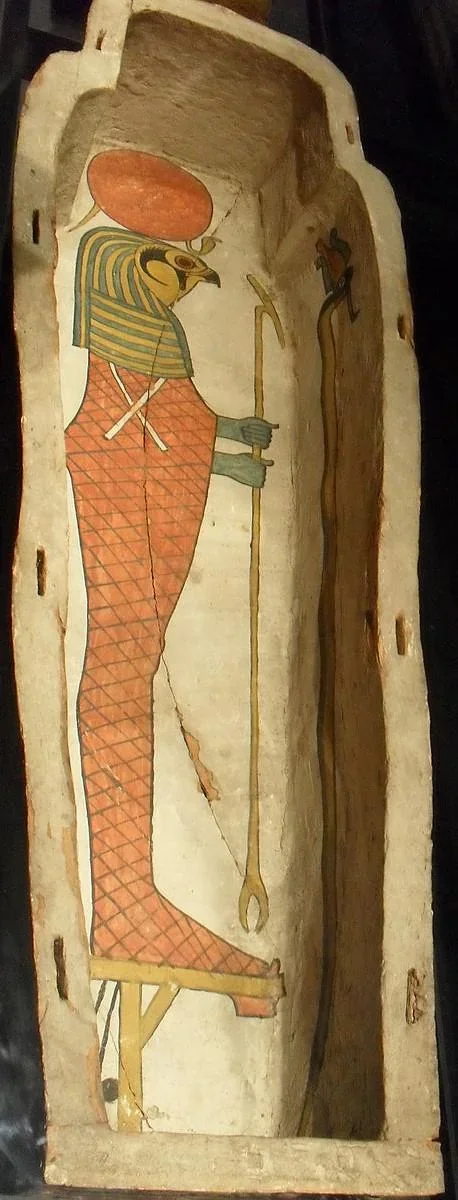

Soon after, Sokar was linked with Osiris as the composite deity Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. This combined figure symbolised three universal aspects: creation, stability, and death. By the New Kingdom, images shifted to a hawk-headed mummy wielding a Was-sceptre, a flail, and a crook, likely a connection to Osiris’s symbols, holding the regal tools. Sokar usually stands on a funerary mound, possibly the primaeval mound, and wears a sun disc, cow horns, and regal cobras similar to the Atef crown. Sometimes he is seen with the White Crown. As a falcon deity, he is frequently associated with Horus and shown wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt.

Figure 11. Ptah-Sokar-Osiris Figure of Nesshutefnut c. 332 BCE Ptolemaic Period.

Figure 12. Figure of Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. Late Period, Saite ca. 600–525 BCE (The Met, Gallery 5).

Also, during the New Kingdom, the Book of the Dead shows Sokar merging the forms of Osiris and Ptah. Consequently, Ptah-Sokar evolved into Sokar-Osiris, representing the nocturnal sun in the fourth and fifth hours of the Amduat. The Sokar priests continued to use the titles once held by the Memphite priests of Ptah in the Old Kingdom; however, they now mainly referred to the high priests of Heliopolis. Ptah-Sokar-Osiris is typically shown as a mummified hawk adorned with royal regalia. However, he is also depicted as a pygmy with a scarab beetle on his head, symbolising Kheper. These representations of Ptah-Sokar-Osiris likely inspired the deity Herodotus called Pataikos. Although Sokar was married to Sekhmet, Sokar is occasionally associated with Nephthys (Hill 2016). Specifically, during the 18th Dynasty, around 1323 BCE, a detailed gold statue of Sokar was placed in King Tut’s tomb. Although some mistakenly think it depicts Horus, the image below is labelled as Horus, but it shows the god mummified, which Horus never is.

Even in the 22nd dynasty (around 945–730 BCE), a Libyan-led dynasty, originating from the Meshwesh tribe, ruled during the Third Intermediate Period, bringing temporary stability but eventually leading to fragmentation. Sokar returned to his original silver connections via images of the god on the silver coffin (which was rarer than gold) of the king Sheshonq II (c. 890 BCE), discovered in Tanis. (Remler 2010:180).

In the Late Period, representations of Sokar became more stylised and detailed in their iconography. The integration of diverse artistic influences, including Hellenistic styles, produced hybrid depictions that blended traditional Egyptian imagery with newer artistic forms. This stylistic combination reflects broader social and political shifts in Egypt as different cultures interacted, influencing how Sokar was depicted. Currently, the available references (Liu 2001, 2023) do not confirm a specific influence of Hellenistic styles on Sokar's iconography.

During Rome's rule over Egypt (198–217 CE), the final known depiction of Sokar—represented as Osiris-Sokar with a falcon's head—was engraved into the Isis temple at Philae. This artwork remains today due to the temple's excellent preservation. Philae stayed accessible longer than any other ancient Egyptian temple, remaining open until Byzantine Emperor Justinian ordered its closure in 535 CE. By that time, most temples had already fallen into ruin centuries earlier (Shmoop Editorial Team, 2008).

The way the body was placed inside a coffin was seen as similar to the soul’s journey into the Duat (the underworld), a mysterious, unseen realm (Figure 12). In the Late Period, the connection between the sarcophagus and the sky becomes clearer. Notably, before the New Kingdom, the Egyptians didn’t distinctly show the sun’s nighttime journey on burial chamber walls. However, one side of coffins featured a drawing of two eyes, symbolising the dead’s rebirth and their ability to see the sun, Re’s, movement through the Duat. This idea became even more vivid in the royal tombs of the New Kingdom, where the interior of the sarcophagus chamber was decorated with scenes depicting the sun’s journey through the underworld at night. The coffin’s lid was semi-circular and adorned with scenes illustrating the sun’s path across the sky. Sometimes, the side walls near the foot and head of the coffin had two columns, representing the pillars supporting the sky and the horizon where the sun rises and falls. This made the coffin lid a symbol of both the sky and the celestial body above the horizon.

Figure 15. Sokar on a coffin, protecting the deceased.

This symbolism appears in the paintings on the wooden coffin of Djeddjehutyiuefankh, a Theban priest of Montu from the 7th century BCE (Ashmolean Museum. AN1895.153). At the front of each coffin are images of the reborn sun, linking the head to the eastern mountains called Bakhu (CT II 375–376) and the foot to the western mountain Manu. Near the foot, there’s an inscription on a column that reads: “An offering given by the king (to) Ptah-Sokar; all necessary secret things are made for him during the festival of Osiris (Hb Wsir), the god, beloved by Djeddjehutyiuefankh.” This refers to the rituals performed during the flood season. Mentioning the Osiris festivals makes sense here because they were connected to the 70-day period when the constellations Orion (representing Osiris) and Sirius appeared invisible—that time marked the gods’ and the individual’s passage into the Duat.

The Impact of Cultural Interactions

The depiction of Sokar also demonstrates the influence of interactions between Egypt and neighbouring cultures. For example, during the Ptolemaic era, Egyptian art more frequently adopted Greek iconographic features. This blending is important because it shows how foreign artistic styles could have affected traditional representations of gods, indicating a shift in cultural identity expressed through art. Nevertheless, the available sources lack detailed evidence to fully confirm this influence (Esler & Pryor, 2020).

Festivals

Festivals for the god Sokar are known as early as the Old Kingdom - most likely. Though by the time of the New Kingdom, the festival had grown to include Thebes, where it became as prominent as the Opet Festival. It is believed that the festival honoured Osiris’s rebirth and emphasised the pharaoh’s ongoing authority (Hill 2016).

During the New Kingdom, Sokar’s cult was particularly significant in Egyptian religion, as shown by the numerous structures built in his honour. The Sokar festival was a key component of the Osirian celebrations during the month of Khoiak, depicting different stages of Osiris’s resurrection after his murder by Set. These celebrations occurred at the start of the agricultural season, with rituals aimed at awakening the soil's vitality and promoting its fertility (Mironova, 2020).

According to the calendar of Ramesses III from Medinet Habu (20th dynasty), the Sokar (Choiak) festival was held in Memphis on the 26th day of Khoiak, the 4th month of Akhet (sowing), a 30-day period between December and January. It was a key funerary celebration within a broader 10-day Osiris festival. The night before, on the 25th of Khoiak, during the ‘festival of two goddesses’ (ntryt), Egyptians made necklaces of five onions and wore them around their necks. These five onions were associated with the teeth of Osiris or Horus and linked to the rite of ‘opening of the mouth’, intended to revive the five senses of a dead person (Mironova, 2020).

This onion celebration likely continued into the next day, as depicted on wall carvings as "The Day of Chewing Onions," where baskets of onions were brought to the temple for Sokar to taste and then used to prepare food for festival attendees. This Onion Day takes place just before the Mysteries of Osiris begin, although this was also described as mid-autumn, as part of the months-long Opet festival. Perhaps there were two onion festivals? Either way, as part of the festivities in Akhet, Sokar’s followers continued to wear the strings of onions around their necks during the day, showing his Underworld aspect. This is because onions were used in embalming people; sometimes the skin, sometimes the entire onion. [Which makes me wonder if that is where the garlic aversion came from for vampires; the underworld doorway, a place where they cannot cross]. When just the skin was used, it would be placed on the eyes and inside the ears to mask the smell (Gahlin 2014). Also, the god was depicted assisting with various tasks, such as digging ditches and canals (Hill 2016, Wilkinson 2003).

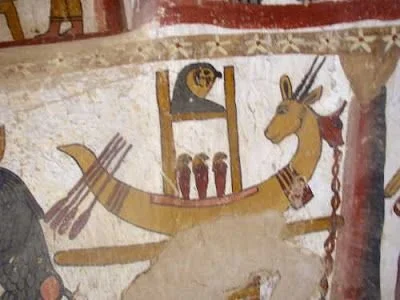

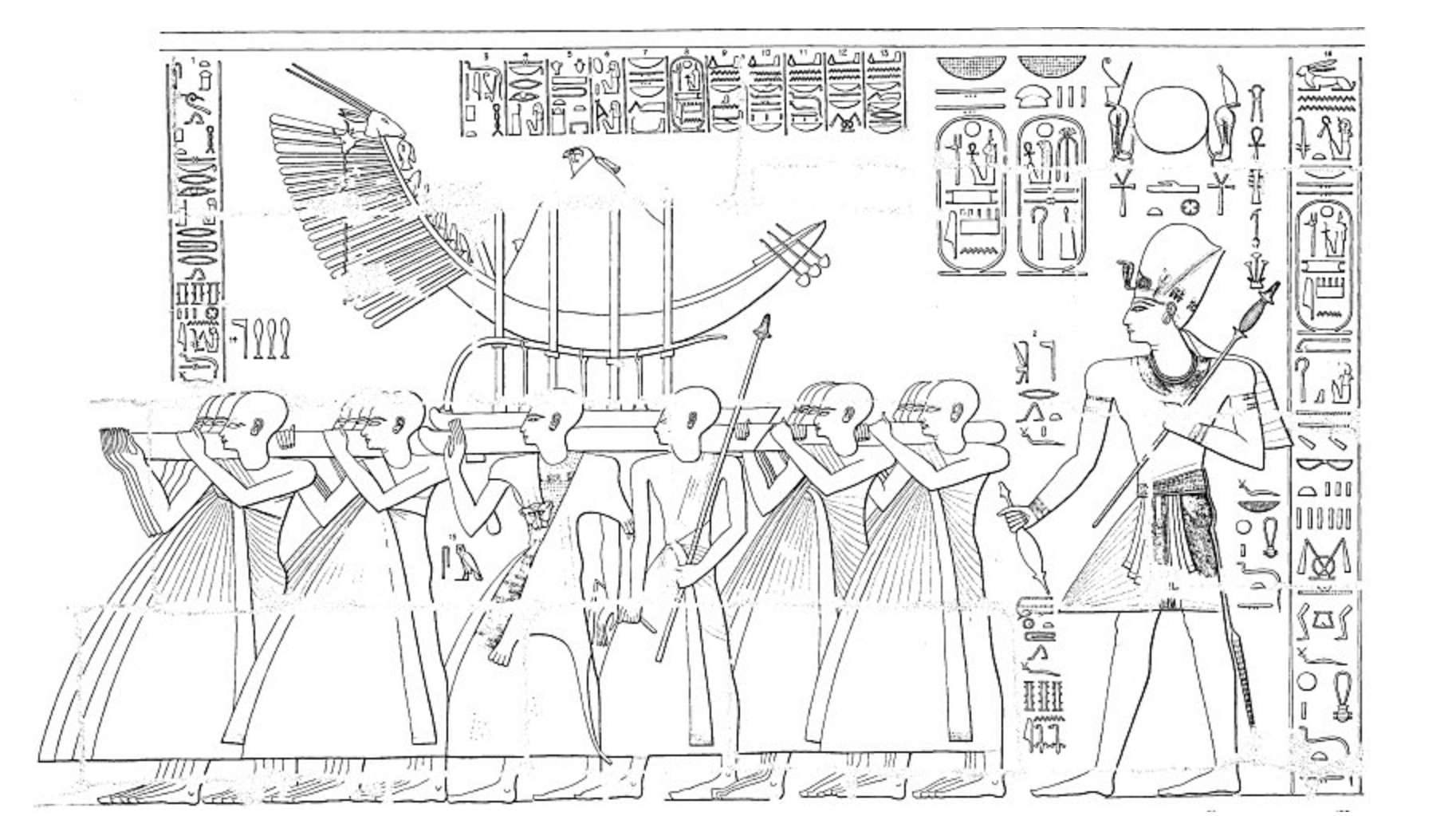

During the festival, various events featured a large statue of the god being carried on a Henu barque, a boat characterised by a high prow shaped like an antelope (Oryx gazella) and included a funerary chest (Hill 2016). Egyptians performed rituals such as hoeing the earth and cattle driving, suggesting Sokar's role as an agricultural deity. People carrying bunches of onions followed Sokar's barque during the ritual procession around the temple walls. This ceremony symbolised the solar journey and invoked magical protection from evil forces (Mironova, 2020). In addition to this procession, worshippers likely visited the necropolis to offer sacrifices to the deceased. Later, the procession moved to the ‘Tent of purification’ (ibw), where funeral rites took place. One of the early rituals of the Osirian festivities — ‘ploughing the soil’ (xbz-tA) — was linked to Sokar’s festival, representing the release of Osiris’ life forces hidden in the soil as seeds. In this context, Sokar, as a god of the dead soil, acted as a mediator between death and Osiris’s rebirth. The Khoiak festivals concluded on the 30th day, with the ritual of raising the djed pillar, symbolising Osiris’ completed resurrection.

Figure 18. The king raising the djad pillar at the festival

During the Ptolemaic period, since the winter solstice coincided with this date, the two events became connected. However, the Sokar festival itself is much older, with references to it dating back to Early Egyptian texts (Biesbroek n.d.). The festival is supposed to symbolise the return of sunlight after the darkest winter days, which connects to Sokar’s realm, the darkest area before Re is brought back to life (Ivanov 2022).

The known example comes from the New Kingdom, specifically a pictorial document found in the second courtyard of Ramses III's temple at Medinet Habu. It depicts the Sokar festival that took place on the 26th of Khoiak, as shown on the south and southeast walls. The main focus is the procession of the Henu-barque, similar to what we see in other images. The divine boat of Sokar is also shown with five other boats, each representing a goddess: Hathor, Wadjet, Sekhmet, Bastet, and Sekhmet again. Of these, three—Hathor and Wadjet in the top part, Bastet at the bottom—each sit on a high throne; one has a small chapel; and the fifth, Sekhmet, has four bars that resemble those on a pr-nw. Above these boats, a repeated symbol probably stands for gAwt (a bundle or tribute), with four or six circles, suggesting it refers to more than one.

These boats are shown loaded with offerings. It’s unlikely that these boats and goddesses appear randomly in the festival, since Sokar is never pictured with a female partner; their appearance must mean something important. These goddesses are clearly connected to the festival: Hathor, as the mother goddess and protector of birth, love, and the dead; Hathor of Dendera, linked to rebirth, growth, and renewal; Bastet, with her complex and sometimes fierce nature; Neith and Sekhmet, warrior goddesses—Neith of war and magic, Sekhmet of fighting and plagues. All of them symbolise different aspects of Sokar, representing parts of the god of potential life within death. (Habu IV 1940, Gaballa & Kitchen 1969, Graindorge-Héreil 1994, Graindorge 1996).

One of the earliest and most notable portable boats was the Henu-barque of Sokar. It was placed on a special sledge called mfx and carried around the walls of Memphis during festivals honouring this god. By the Old Kingdom, the Henu-barque had developed a distinctive shape: it rested on a frame reinforced by four legs and mounted on a sledge. Its upturned prow featured an antelope head facing backwards and horizontal stays, while the stern sloped upwards and was decorated with two steering oars. Inside the boat, a falcon was often depicted. This original design continued into the New Kingdom, with added decoration. Sometimes, behind the antelope's head, you could see the head of a bull facing forward, with a cord or leash hanging from its mouth. Also common were a bolti-fish and six small falcons behind the prow. The number of steering oars increased over time, reaching four. During the New Kingdom, a small chapel was placed amidships; it was topped with or squatting with a falcon, and the sacred image inside was visible. (Abdel–Raziq 2011).

Figure 19. Henu-barque

Bastet was frequently depicted as a woman with a lioness's head and a uraeus (serpent)(Geissen & Weber 2007, Chr 2002, Malek 1997). Of particular importance is the upturned stern, which also features an antelope head facing backwards while sniffing a lotus flower bud. This design resembles the form of the god Sokar's bark prow and, to some extent, that of Nekhbet's barue. The antelope, regarded as the sacred animal of the desert, was sacrificed during the New Kingdom, with its head offered to Sokar or his barque. (Abdel–Raziq 2011, Gardiner 1911, Gaballa 1972).

In several tombs, the scenes of everyday life and offerings are depicted alongside the lists of festivals dedicated to solar and lunar deities. For example, in the Saqqara tombs of the nobles Ihy (usurped by the Princess Idut) (Dyn. 5–6) and Kagemni (Dyn. 6) 14, the scenes of offerings and slaughtering a bull are next to the list of feasts associated with the cults of Thoth, Osiris, Sokar, Re (Porter 1974: 619, Porter 1974: 524, Macramallah 1935). Such a neighbourhood of pictures and “festival” inscriptions shows the semantic relationship between everyday life and the solar-lunar cycle, between the deceased’s world and the world of gods.

Fest-Summary

Significant festivals, particularly the Henu festival, were central to the formal worship of Sokar. Celebrated in the final month of the inundation season, these festivities were marked by detailed processions. The ritualistic "tilling of the earth" stood as a powerful symbol of new life, mirroring the ancient Egyptian belief in the deceased's eventual resurrection. The Henu barque was a fundamental part of the festival procession, acting as a symbol for the underworld journey. These public events strengthened the community’s belief in the life-and-death cycle centred on Sokar. Found throughout ancient records and tombs, his legacy remains tied to the idea of an ordered, cyclical cosmos. As a symbol of transformation and eternal hope, Sokar represents the belief that death was a required step toward a new and better existence.

Ramesses III Temple Walls

The most complete depictions of the Sokar festival cover the entire upper register of the south wall within the Second Court of Ramesses III's temple, extending to the southern portion of the east wall (Espigraphic Survey, Medinet Habu IV (OIP 51; 1940) pls. 196C-D, 218-226 (reproduced on tab. I and II [figs. 1 and 2 reproduce pl. 196 C, fig. 3 reproduces pl. 196 D]).

Before the Procession: (lines 24-25)

'The gods who accompany Sokar, may they grant eternity as King of the Two Lands to Ramesses III, (and) may they incline their hearts towards Ramesses III, that he may celebrate jubilees forever'.

Lower Row. (lines 55-57)

'Praise to thee, O Sokar-Osiris, great god, Lord of Shetayet! Mayest thou give life, stability, and dominion to Ramesses III forever.'

Scene I

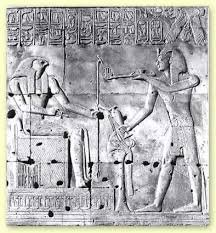

The King, 'elevating offerings to his father', is standing before Sokar, who sits upon a throne and the dais, and promises him a lifespan like Rēf and earthly kingship like Harsiese, two names of ancient people, whether legendary or real (Gaballa 1969). [Rēf didn’t come up with any results other than the god Re. Harsiese was the name of multiple people: two priests, one prophet, and one king. Unfortunately, the king ruled during the 22nd dynasty, 270-300 years after Ramesses III ruled when this stela was made (Broekman 2002).] Behind Sokar sit two groups of three deities, indicating a plurality of gods. The upper group is the 'Ennead within the Shetayeť, while the lower group is the 'Ennead residing in the Great Mansion'. The two enneads together promise the customary health, life, and dominion eternally.

Scene III

Wearing a headcloth, the King is 'performing a Litany of Offerings to Sokar in all his names', and stands before the characteristic Henu-barque of Sokar housed within a shrine accompanied by the usual ritual accoutrement. Between the king and the god is an “offering formula” called, in ancient Egyptian, ḥtp-ḏj-nsw(t), which translates to "an offering given by the king" and is followed by the name of a deity and a list of offerings. Also between the king and god are altars, covered with the litany of the forms of Sokar, as well as a text addressed to Sokar:

“Shetayet; in the Residence; in Heryt-ib; in Restau presiding over Restau; upon the desert hills; upon his sand; his places within Restau; in Tjanent; presiding over the divine booth of the craftsmen; in Sahty; in Nedyt; in Ně-Weretí; in She-Ra-minen; in the land of ...; in Qefenu; in Pdw-št; in the Maaty-barque; in Gs-in Siut; in Biket; in his places with within Lower Egypt; in the foreign Lake; in the Northern Lake; in his temples; in all his establishments, in his divine booths; in every place in which by the gift of King Ramesses III Festival, eternally.”

Figure 20. Ramesses making Litany of Offerings to Sokar.

Scene IV

In short, Scene IV: The Royal Procession and Barque depicts the King following the god during a "promenade" as the procession moves around the walls. The Sokar Henu-barque is carried by sixteen priests, and the scene is officially named "Drawing along Ptah-Sokar-Osiris in order to go round the Walls, by the King himself". The god then makes the usual promises of valour, provision, and sustenance to the King.

Figure 21. Ramesses III accompanies the barque of Sokar in the procession (Medinet Habu 1940, pl. 223).

Scene V

Known as “Sokar Enters” or the “Bringing in Sokar” ceremony, after a priest carries a falcon on a banner labelled as 'Horus upon his papyrus-staff'. The second part of the scene shows two lines of courtiers, royal sons, and prophets holding the long ends of a cord, with the midpoint held by Ramesses III, following them. Preceding them walks a lector-priest (called kheri-heb in ancient Egyptian, meaning "carrier of the book of ritual") reciting from a scroll the main text of this scene, which are words which the chief lector-priest utters when Sokar enters, “Hail - Be triumphant, triumphant, O Sovereign!” (Egyptian Texts : Bringing in Sokar, 2023).

Scene VI

It’s the largest scene in the whole series and is divided into two rows. In front, priests carry five sacred boats, Nefertem banners (the blue lotus symbolised the god of creation), and a box of five geese. The whole group is preceded by two priests beating time and others, cewab-priests carrying other banners, and a 'scribe of the roll of divine offerings’ with his palette. The foremost wab on the lower row carries a mace, before which onlookers fall down in adoration, while the priest, all the way in the back of this row, offers incense to Ramesses III. The latter follows the procession, attended by two rows of personal servants.

The Text over the Procession in the Upper Row says:

“The King of Upper and Lower Egypt he invokes his father Sokar-Osiris. Who protects his father: "I shall celebrate at its (proper) time. I shall hide his weariness in Abydos, I shall conceal the hidden things in this night of the festival of the Weary-hearted one. I shall drive away the aggressor, and restrain his confederates. I fill the offering-tables and vessels. I restore the altars. I endow him who is in his chapel.”

-and-

“Hail to thee, my father Osiris. Thou art exalted upon thy standard. Thy Great Crown is in the hearts of those who are yonder, while the Ennead are in thy following. They give thee praise and adoration in the residence of Nefertem, in Busiris, in the nome of Mendes, in Abydos, and in the temple of Ramesses III in the estate of Amun; as long as thou endurest, mayest thou be living, happy, powerful, stable, and protected in the necropolis.”

There are a bunch more hails to various other gods and to Rameses III from the priests as the barques are carried through the streets.

During the Festival of Sokar, the chief lector-priest recited a series of ceremonial chants and expressions of devotion during the procession. These words included praise and celebration of the "Sovereign," calling for their victory. The priest also commented on the god’s sweet fragrance, showing sensory appreciation. He expressed his dedication to performing actions the god loves and praises, demonstrating his commitment to service. The speech also mentioned acts of reverence, such as kissing the earth and “opening the way” for the “favoured ones of Abydos”, reflecting ritual humility. The speech also contained calls for protection and references to specific figures, such as a “son of a prophet”. These words are quite similar to passages found in ancient papyri, such as the Papyrus Bremner-Rhind, and texts like the “Going round the walls” passage on the Polmero Stone, making them seem rooted in even more ancient traditions for the time they were carved.

So long story short,

The scenes of the Festival of Sokar at the temple of Rameses III in Medinet Habu are located in the upper register of the south and southeast walls of the second courtyard. These pictorial documents are divided into six distinct scenes:

Scene I: Offerings to Sokar – Rameses III is depicted elevating offerings to Sokar, who sits upon a throne and dais. Two groups of three deities, the "Enneads," sit behind the god and promise the King health and eternal dominion.

Scene II: Censing for Khnum – The King, wearing the Atef crown, performs a censing ritual for the god Khnum, who is described as "presiding over the walls".

Scene III: Litany of Offerings – Rameses III performs a "Litany of Offerings" to Sokar in all his names while standing before the Henu-barque. The text includes a lengthy list of the god's various forms and locations.

Scene IV: The Royal Procession – Titled "Drawing along Ptah-Sokar-Osiris in order to go round the Walls," this scene shows sixteen priests carrying the Henu-barque as the King follows behind during the ceremonial promenade.

Scene V: Symbols of Nefertem and Horus – This scene features eighteen priests and a Sem-priest carrying the symbol of Nefertem, followed by a priest with a falcon standard representing Horus. The King follows two rows of courtiers and royal sons.

Scene VI: The Grand Procession – The largest scene in the series, it is divided into two rows and features priests carrying five sacred boats, Nefertem banners, and a box of five geese. The procession is led by musicians and scribes, while Rameses III follows at the rear.

An academic article on the Festival of Sokar examines uncertainty about whether certain early records specifically refer to a Sokar festival, drawing on various iconographic and textual clues. The barque's ambiguous imagery, including the "Maaty boat" depicted on the Palermo Stone and mentioned in the Pyramid Texts, is not uniquely linked to Sokar's Henu-barque. Instead, it is part of a broader group of divine vessels, which also includes the boats of the sun god Re and the king. Scholars have proposed that the Maaty boat might have solar connotations; for instance, King Neferirkare is said to have built a Maaty boat at his solar temple, complicating its identification as solely a Sokar-related object. The Palermo Stone depicts the Maaty boat with two falcons—one often identified as Sokar hnty M3'ty and the other possibly representing the king, the Horus-king —suggesting the festival could highlight royal authority as well as Sokar worship. Furthermore, variations between texts such as those in Medinet Habu and the Bremner-Rhind Papyrus reflect textual discrepancies, likely due to hieratic corruptions, which hinder a precise understanding of the festival’s original purpose and the liturgies performed during the processions.

Direct Myths

Pyramid Texts

In the Pyramid Texts (PT), Sokar is primarily associated with roles involving the purification, transformation, and protection of the deceased king. Highlighting specific instances: the Vehicle of Transformation, where Horus lifting Osiris is compared to the henu-barque carrying Sokar (PT 364, 645, 647). It also mentions Spirit Creation, noting that Horus created a spirit of his father as Ha, Min, and Sokar (PT 610). Sokar is explicitly connected to Purification, responsible for purifying the dead (PT 479). As the Celestial Ferryman, the deceased requests Thoth to be ferried on the tip of his wing as "Sokar who presides over the Bark of Righteousness" (PT 566). The Ennoblement role is evident when the “watchers of Nekhen” are described as ennobling the deceased as Sokar (PT 483). Finally, in The Breaking of the Egg, Sokar uses a self-made harpoon to pierce the egg containing the unformed king, allowing him to ascend into the sky (PT 669). (Butler 2020).

Coffin Texts

In the Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts, especially in Volume I, Spells 1-354, Sokar is a vital funerary deity whose presence is intricately woven into spells that protect, purify, and transform the deceased into a blessed spirit, known as an akh. The process begins with purification and ritual transformation, where Sokar is often invoked to perform the essential cleansing of the deceased and keep evil spirits away from them in the afterlife, like in Spell 479, where he's specifically told to purify the deceased. This purification is crucial for enabling the soul's entry into the sacred regions of the afterlife. Following this, the spells focus on transforming the deceased into an akh, or an ennobled spirit. By being identified with Sokar, the deceased acquires the god's power to transcend the physical tomb and ascend toward the celestial realm.

Sokar's association with the necropolis and the underworld is also prominent. Which is when he’s famously titled "He of Rostau," referring to the openings or pathways into the underworld. Spells within this volume guide the deceased through these perilous subterranean regions, believed to be filled with traps and snares. Additionally, Sokar’s role extends to Memphis, where he is the primary deity of the burial grounds. Here, he provides localised protection for those buried in wooden coffins, reinforcing his guardianship over the dead. It also mentions Sokar’s vessels, which further emphasise Sokar’s mythos.

In Spell 669, Sokar uses a harpoon to break open an egg containing the unformed king, so he can fly to the sky and become immortal. As he’s also connected to Rostau, the entrance to the underworld, guiding souls through dangerous parts. The text also reflects a trend of syncretism, wherein Sokar merged with Ptah and Osiris. While Volume I contains many distinct spells, this combination signifies the integration of different divine aspects intended to aid the deceased on their journey and in the afterlife.

From the “Hymn to Osiris-Sokar” (Isis Temple Chants)

The mentions that I found the excess use of fear may have been from the "Hymn to Osiris-Sokar" (Isis Temple Chants/ liturgies such as The Burden of Isis, which contains the following lines:

"Hymn to Osiris-Sokar. FORMULAE for the bringing in of Osiris-Sokar, in connection with the mysteries spoken heretofore."

"Behold the lord of fear, who causeth himself to come into being!"

"Hail, royal one, coming forth in the body!" (addressed to Osiris-Sokar).

(Mackenzie 2020).

It seems like Osiris-Sokar being known as 'the lord of fear who causes himself to come into being' had to be a later idea, especially since Sokar had already been syncretised with Osiris. Sokar is considered one of the oldest Egyptian gods; in other versions, having been merged with both Re and Osiris. Besides his primal traits, he is also seen as 'the mysterious one,' a 'figure unknown to mankind,' and a 'hidden god.' Other gods in this hidden category include Amon and Neith. Sokar's reputation mainly centres on being 'the lord of fear,' in this ‘hidden god’ context, highlighting his role in evoking awe and fear among the Egyptian pantheon and worshippers. (Mackenzie 2020).

Soul and Egg Myth

The "soul and egg" myth, often called the chaos-egg myth, is an ancient and enduring belief related to the creation of the world and the transmigration of souls. In the myth’s depiction of creation, the Chaos-Egg appears in various forms. One version describes the sun god emerging as a shining egg floating atop the primordial waters, known as Nu. Another variation identifies the sun as an egg laid by the chaos goose, referred to as the "Great Crackler," which is said to have crackled loudly at the dawn of time. In some traditions, particularly at Heliopolis, the egg was shaped by artisan gods such as Ptah or Khnum on a potter's wheel. (Mackenzie 2020).

The myth also emphasises the idea that deities or other beings can conceal their souls or essences within an egg or other objects to ensure their continued existence or transformation. The souls of gods such as Re, Ptah, and Khnumu are believed to reside within the chaos egg, a motif also found in Hindu and Chinese mythology. For instance, Osiris is described as hiding his essence within the shrine of Amon. His manifestations—such as a tree, the Apis bull, a boar, and a goose—are considered different stages or vessels for his soul. (Mackenzie 2020).

The myth is illustrated in the story of Anpu and Bata, where Bata hides his soul in various forms: a blossom, a bull, and a tree, before being reborn as the "husband of his mother." Comparisons have also been drawn between these Egyptian beliefs and European folklore, in which a giant conceals his soul in an egg housed within a series of animals, such as within a duck, within a fish, and within a deer. (Mackenzie 2020).

This myth also sheds light on why certain gods are viewed as "hidden" or mysterious. Deities like Amon, Sokar, and Neith are associated with this concept of a concealed, internal soul. Even in later religious texts, such as the hymn to the sun disk (Aten) during the reign of Akhenaten, the "air of life" is depicted as residing within the egg, demonstrating the persistence of this mythological theme. (Mackenzie 2020).

Evolutionary Syncretism

What’s interesting about Sokar, by himself, doesn’t have an equivalent in any other culture of or around the period. He is singularly Egyptian. This does make sense because he is a god of the mummified and a guardian of gates, which are pretty individually specialised aspects in Egyptian culture. But even Anubis, as the god of mummification, was syncretised with the god Hermes. This was a consequence of their shared role as psychopomps, those who guide souls to the afterlife. Sokar doesn’t guide; he’s just there, guarding the gates. He doesn’t get a whole death myth, that I know of; he’s the personification of the physical part of the body and its possibility for resurrection, which appears at the end of the 5th hour of night (Sokar 2019). Some academics will compare Sokar with Hades/Pluto, the Greek/Roman god of the Underworld. Which could work, but Hades is often syncretised with Osiris since he’s the Lord of the Underworld, even though Osiris is often equated with Dionysus by Plutarch and Herodotus explicitly in their writings because of the gods’ shared roles as gods of vegetation, wine, death, and rebirth, as well as their similar mythologies of being dismembered and resurrected. Herodotus in particular identified the Egyptian god Osiris as the Greek god Dionysus, stating,

"Osiris is, in the Greek language, Dionysus".

This identification highlights the Greco-Egyptian syncretism of the 5th century BCE. Poor Sokar.

But, because the real treasure is the friends we made along the way, Sokar was bundled up with Ptah for a while, starting in the Middle Kingdom, and then whoever decided these things added Osiris in the late period, after 1000 BCE. In other words, Sokar’s identity was ultimately merged with other major deities to form the triad Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. This composite god symbolised the complete cycle of the soul, with Ptah representing creation and stability, as the creator god of Memphis; Sokar embodying death, burial, and mastery of the necropolis, as the patron of the Memphite necropolis and Osiris signifying rebirth and the final judgment of the dead as the chief god of the afterlife and ruler of the underworld and rebirth god.

Popular in funerary contexts from 1000 BCE onward, this composite deity represents the complete cycle of creation, death, and resurrection, often depicted on mummy-like figurines placed in tombs for rebirth in the afterlife (Ptah-Sokar-Osiris n.d.). This statuette of the god symbolises creation (Ptah), the arduous journey through the underworld (Sokar), and the promise of eternal life (Osiris) for the mummy, as a sort of protective blessing. These figures, often hollow, held mummified offerings or texts and acted as coffins for the dead’s journey to the afterlife. The Memphite cult, especially in Memphis, focused on this trio, combining Sokar and Osiris into one god for funerals.

Sokar is important in the underworld journey, guiding the sun god Re and guarding him from chaos (weirdly, also like a psychopomp), and then linked to Ptah's creative power that brings new life. The combined form was depicted as a slender, mummiform figure, often with the head of Sokar (hawk-headed) or a human face. He wears the crown of Osiris (atef crown-with the ostich feathers) or Ptah's skullcap, often with ram’s horns and sun disk. The body may also feature Osiris figures or inscriptions detailing spells for the afterlife. Examples of the statuettes are often a linen-wrapped corn mummies placed inside this hollow mummiform figure to represent the agricultural image of rebirth in the afterlife. The body of the actual god, therefore, is supposed to function as a coffin itself.

But even with his new triple god status, Sokar wasn’t one that other cultures, not together with the earlier cultures of the Phoenicians, Babylonians, etc., or later with the Greeks or Romans, ever bothered to sync. So, good news, his myth is pretty stable, if shallow.

Funerary Texts

The Amduat, meaning ‘that which is in the netherworld,’ is also known as the Book of the Hidden Chamber. It is a funerary text that describes Re’s journey of renewal. The other main text is the Book of Gates. These two texts differ as they give separate descriptions of Re’s passage through the 12 hours of night during Egypt’s New Kingdom period, serving as guides through the Duat, or the underworld. The Amduat focuses on time, highlighting hours and hidden chambers, while the Book of Gates emphasises space, featuring guarded gates (or pylons) which require specific knowledge to pass. So, think of the Amduat as a journey through time, and of the Gates as a journey through portals in space.

The Amduat, or 'What is Done in the Underworld,' centring on hidden chambers and the progression of time over twelve hours, is structured into three horizontal sections—top, middle, and bottom—each with vertical columns representing one hour. Important themes include the sun god's journey through twelve regions, with a focus on transformation and the underworld's hidden aspects. The Gate Book follows the name and talks about the physical gates or pylons that separate different times or regions. It explains the dangers involved and what you need to know to get through them. The structure is based on twelve hours, each with its own named gate guarded by snakes and gods, especially along the banks of the underworld river. It also shows how the dead are judged in the later hours, dividing people into four groups—Reth (Egyptians), Aamu (Asiatics), Nehsey (Nubians), and Themehu (Libyans)—and gives instructions on the offerings needed to pass each gate.

It’s not an exact map for people who died, but in later Kingdoms pharaohs and other super-rich people were painted or carved into the stories on their tomb walls and coffins, along with Re on his barque. But its main aim is to provide a description of the underworld so that the deceased, as well as the living, can become familiar with what to expect when their journey into the afterlife begins. Out of the 12 hours, Sokar appears, at least his land is being travelled through, in 2 back-to-back hours. He’s got a lot of land.

The domain of Sokar was believed to be deep in the underworld; it is mentioned in the fourth and fifth hours of the Amduat, which decorated several royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings and also appeared on later papyri.

In the 4th hour, Re arrives at Imhet or the Desert of Rosetau, meaning ‘act of towing’, the desolate, dark, and bone-dry desert of Sokar is guarded by snakes, with a ground also littered by more snakes. Thoth and Sokar protect the sun god as he makes his slow progress through the desert. Owing to the name of the region, the barque is being towed by either four gods or representations of the four groups of people that the dead were divided into (Egyptians, Libyans, Nubians, and Asiatics). By this stage, it’s so far into the duat that there is no light. Descriptions state that the sun god has penetrated so far into the underworld and moved so far away from his own light that he cannot see, relying solely on his voice to navigate himself and his crew out of the darkness (Abt & Hornung 2003: 58–61, Richter 2008, Minnick, 2021). However, in some versions in which Re is dead (or at least sleeping) and with no water to cross, his solar barque transforms into a double-headed, fire-breathing serpent, pulling double duty, using its own sense to “see” as Re's only means to cross this pitch-black desert. This hour stands out visually from the others, featuring a large sand path that zig-zags through all three levels, connecting them, yet making Re’s journey difficult due to multiple doors along the way (Abt & Hornung 2003: 58–61, Minnick, 2021, Remler 2010).

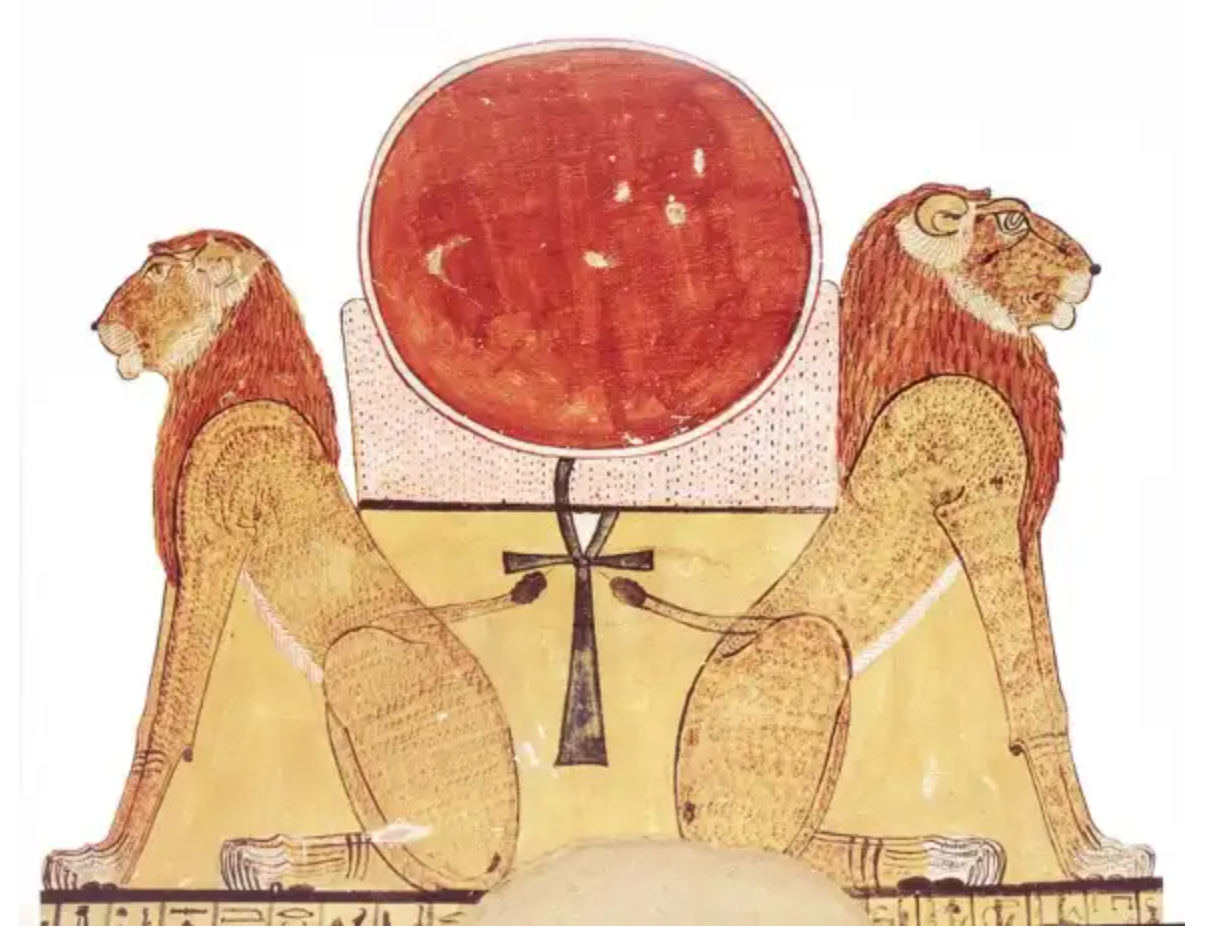

In hour 5, the land of Sokar continues, as does the serpent-barque. In this hour, fourteen deities (seven gods and seven goddesses) representing the days of a lunar month tow the boat (Remler 2010). This is the region of opposites, seen in the waters of Nun uniting with the desert lands of Sokar. Osiris's burial mound is depicted at the top register, with Khepri crawling out, symbolising the eventual rebirth of Re, which begins with the recovery of Osiris's body (Abt & Hornung 2003: 68–73, Minnick, 2021). There is a narrow passageway being attempted to get through, prompting all the friendly beings of this region, including the scarab representation of Khepri, to help pull the boat before crawling into Re to revive him. An oval representing the 'Cavern of Sokar' is present on the bottom register, with the god himself being contained by a lake of fire surrounding the cavern (Abt & Hornung 2003: 68–73, Minnick, 2021, Remler 2010). As the journey reaches the end of the fifth hour, the travellers approach the secret cave of Sokar, which the sun must pass over, guarded by Aker lions called Duaj (“yesterday”) and Sefer (“tomorrow”) (San, 2022). This cave is a crucial point of transition and hidden power where the sun god undergoes renewal before returning to the solar boat in the sixth hour. Inside the cave, Sokar restrains the winged serpent Apep, representing chaos. (Hill 2016, Remler 2010, San 2022).

Figure 22. Cave Guardians the Aker lions

Based on these depictions, some researchers speculate that Rostau was located near Gebel Gibli, close to the Great Pyramid, and that the Tomb of Sokar, as part of the underground complex, remains undiscovered beneath the sands near the mysterious gateway and the enclosure wall known as the “Wall of the Crow” (Figures 23 & 24). To date, there is no conclusive evidence to support or refute this hypothesis. (Hill 2016).

In these hours, Sokar is often depicted in a “hidden” form, such as a falcon-headed god standing upon a winged serpent, representing the potential for resurrection even in the deepest darkness (Remler 2010).

Figure 25. Sokar holding down Apep in the cave.

I just have to mention that he was called, in several myths, the ‘dreaded Sokar’. This plays into the fact that he was both an underworld god and a hidden god. While that would not automatically make him evil, it does make him mysterious, and people often fear what they don’t understand. It does remind me of all the mystery cults in Greece, especially that of ‘dread Persephone’, Hades’s queen of the underworld. People often wouldn’t have spoken her true (?) name out of fear of her attention being drawn to them, especially since she was a goddess of death, so they referred to her as Kore, or maiden. While Sokar is sometimes known as the God of fear today, this may be partially explained by the connection between fear and evil. The leaders tell their followers to be afraid of cults or groups that may take away their power, just as they would later do with Lucifer or Satan.

Stargate Devil

Figure 26. Sokar in Stargate SG1

[Quick Aside: It’s so weird, I was wrong the entire way through the show, thinking that Sokar was the crocodile god of the Nile. I know, I know, people are yelling at me through your devices; “that’s Sobek!” I was thinking, ‘huh, you know maybe the writers thought crocodile god → crocodiles → scary → satan’s scary → satan’. But obviously that doesn’t work at all. So why? I mean, they grabbed all the main gods, good or not great in some later iterations of the myths (see Seth). But they don’t even have Sobek, and Sokar, while maybe not as well known, is a main god of the Underworld, and is THE main Underworld god after being combined with Osiris and Ptah. Plus, I don’t think Ptah is ever mentioned in the show, but he’s got a long backstory on the Stargate Wiki. This includes the ally-ship he had with Sokar, perhaps as a tip of the crown to the original triad. In any case, huge oversight.]

But they did the real version so dirty, which shouldn’t be surprising at this point.

In the show, Sokar, played by David Palffy, is a powerful Goa'uld System Lord known for his cruelty and sadism. Unlike most Goa'uld, his followers serve him mainly out of fear rather than reverence, as he prefers to be feared rather than worshipped. Sokar first appears in Season 2, episode 18, "Serpent's Song," when his forces attack Earth after Apophis dies at the SGC in relative peace. After his death and that of his host, they send the body through the Stargate to the coordinates where he was initially retrieved. According to the Tok'ra, Sokar is believed to have recovered and revived his body, only to be repeatedly tortured. (As mentioned in my Apophis vs. Apep episode, I really hope the host wouldn’t be revived just to endure hell again.)

In Season 3, episode 8, "Demons," his name is mentioned by the Unas serving as his emissary in a medieval village where he is worshipped as THE Devil [could it be SATAN! Yes]. Also, in Season 3, the two-part story "Jolinar's Memories / The Devil You Know" (episodes 12 and 13), SG-1 tries to rescue Jacob Carter/Selmac from Sokar's hellish prison moon, Ne'tu. Sokar is a short-lived recurring threat (after 1999, when his first “appearance” is), appearing mostly through holograms or references, and his influence drives key plotlines, especially those involving the Tok'ra and Apophis's return.

Key Biographical Events

Early History on Earth

When the Goa'uld first arrived on Earth, Sokar established himself as a god of death by exploiting humanity's deepest fears. He aligned himself with underworld demons, including being the Biblical Satan, and initially possessed an Unas host before transitioning to a human host. During the Second Goa'uld Dynasty, Sokar deposed Re and took control from Memphis (echoing the origins of the real god). To conceal his domain, he used a device called the “sun-shade” to shroud the land in continuous darkness, creating an environment where Unas and monsters could roam freely. This sun-shade device was historically employed on Earth to maintain perpetual night over Memphis.

Exile and Re-emergence

Back in the day, Sokar's defeat and exile stemmed from a vengeful Re, who formed an alliance with Apophis and Cronus to annihilate his forces. Although believed to have been destroyed, Sokar persisted as a minor power for millennia. He eventually conquered Delmak, making it his new home planet, and terraformed its moon, Netu, transforming it into a hellish prison world that reflected his mythology. By 1999, Sokar re-emerged to challenge the other System Lords, launching attacks on Earth and engaging in conflict with Henu'ur. After millennia in exile, he returned to attack Earth using a particle accelerator through the Stargate and initiated a series of major military and psychological assaults against both Earth and his rival System Lords.

His notable actions during that year included:

Attacks on Earth and Rival Gods

The conflict with Henu'ur involved direct combat, as he fought Henu'ur while also attacking Earth. After Apophis escaped to Earth and sought asylum, Sokar attacked Stargate Command by utilising a particle accelerator connected through the Stargate to heat and damage the iris, intending to force the SGC to surrender Apophis. When Apophis eventually died on Earth and his body was returned, Sokar used a sarcophagus to revive and torture him repeatedly on Netu.

Strategic Expansion & Demise

Sokar went all out with a massive military buildup, building a fleet ten times bigger than what the Tok'ra thought possible. His plan was to team up and strike against six of the main System Lords so he could control the galaxy. On top of that, he managed to capture Jacob Carter and Selmak and locked them up on Netu. This move basically baited SG-1 into a rescue mission, which didn't go well for the “god” when Apophis rose up again and ended with Sokar's death when the Tok'ra managed to use a weapon to mess up Netu’s core. This caused a huge explosion that destroyed the moon, taking out his Ha'tak flagship while he was in orbit—yeah, not his smartest move.

Personality and Rule

Sokar was known for being exceptionally sadistic and cruel, even more so than most other Goa'uld. His followers served him out of pure fear, not because they believed in him or worshipped him. He loved making people afraid of him more than anything else. He often used torture merely for his own amusement, taking pleasure in tormenting his victims and prolonging their suffering, sometimes even doing the torturing himself. He was one of the few modern Goa'uld who still used Unas as high-ranking agents and warriors, demonstrating his value of their strength and loyalty. Sokar was deeply influenced by the mythological concept of Hell from Earth, and he took that idea very seriously. To reflect his obsession with darkness and torment, he transformed his worlds into nightmarish wastelands, almost like a living hell. He also adopted a demonic persona, modelling himself on underworld deities and even the biblical Satan, to enhance his terrifying image.

Figure 27. Unas in the Medieval Village

As a ruler, Sokar was an iron-fisted despot. He never tried to reward or please his subjects; instead, he ruled through total oppression. His people had no privacy or safety and lived under constant threat of his wrath. He was largely alone in his power, with very few allies— not even other System Lords trusted him. Sokar saw others either as servants to be exploited or as enemies to be destroyed. He liked to make himself seem even more frightening by adopting a dramatic, intimidating appearance. He had pale skin and glowing red eyes, and he spoke in a twisted, menacing way. He often surrounded himself with flames to emphasise his role as “the Devil”, further adding to his demonic reputation and terrifying presence.

The Cult of Sokar

An intelligence and religious network founded by the Goa'uld Sokar to spy on his rivals.

Operations and Purpose

The cult's primary function was to serve as an espionage network, with operatives stationed throughout the galaxy to monitor the System Lords. In addition to intelligence gathering, the cult was also employed for sabotage and assassinations. Members undertaking high-risk missions were often expected not to survive, viewing their participation as a sacrificial act. Communication within the network was maintained through a chain of comrades, recording devices, and communication spheres, ensuring information ultimately reached Sokar.

Membership and Devotion

The cult was made up of all kinds of followers: Jaffa, humans, Unas, and at least one Goa'uld. They were super devoted, doing all sorts of strange rituals and sacrifices while worshipping Sokar's so-called “demonic ways”. If someone lied or reported false information, they believed they'd face eternal damnation, which they thought was even worse than death. The cultists also believed that once Sokar took over the galaxy, they'd get rewarded with power as his right-hand lords.

Iconographic Analysis and Modern Interpretations

It’s difficult to underestimate how much art tells us about Sokar’s history. By examining how his image changed over time, experts can map the evolution of Egyptian religious and social beliefs. This includes examining how modern art movements still engage with these ancient themes (Stedman, 2014), though it’s worth noting that some scholarly links in this area are a bit loose (Williams, 1993). Today's research focused on the “why” and “how” behind Sokar’s appearances in modern interpretations and shows. Essentially, you need to understand the cultural context to truly grasp his modern artistic significance (Liu, 2023), although we are still waiting for more concrete evidence to support some of these ideas.

[And just for fun, Sokar makes a cameo in the OG Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (specifically the Deities & Demigods and Legends & Lore books). In this version, he’s a "lesser god of light" who can literally blast undead away with rays of light from his hands. He’s listed as Neutral Good and acts as the go-to protector for Egyptian souls with that same alignment. While the game ignores his famous “triple persona”, but his symbol—a hawk-headed mummy holding an ankh—hints at that connection anyway. (Ward & Kuntz 1984:48).]

Conclusion

The themes of Sokar's portrayal evolved from a specific guardian of the dead to a complex symbol of universal cycles, while his importance to art today lies in his role as a subject for iconological analysis and modern cultural reimagining.

Tracing Sokar’s history shows a significant shift in how he was seen and depicted. He started out as a simple hawk totem but eventually evolved into a mummified, falcon-headed figure by the New Kingdom, often shown standing on a burial mound in full royal gear. A considerable part of this change was his "syncretism," where he merged with other gods to become Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. This move transformed him from a local graveyard guardian into a universal symbol of the cycle of creation, death, and rebirth. His role also went from being purely about physical funeral rites—like the “Opening of the Mouth” ceremony—to becoming a celestial powerhouse. In later texts like the Amduat, he’s a main figure in the sun's nighttime journey, representing hope and life even in the pitch-black underworld. By the end of the Ptolemaic era, his style even began to blend with some Hellenistic styles as Egypt began interacting more with other cultures.

Sokar’s legacy shows why he’s still a big deal in art and academia today. Experts use his changing imagery as a roadmap to understand how ancient social and religious values shifted over thousands of years. Beyond textbooks, modern art movements still draw on his themes to explore deep concepts such as life and transformation. Even pop culture gets in on it; for example, Stargate SG-1 flipped his original “rebirth” role, turning him into a “Devil” archetype, reflecting our modern habit of linking underworld gods to fear and evil. Ultimately, research into Sokar helps bridge the gap between ancient rituals and the way we express those same ideas in modern exhibitions.

Tracking how Sokar’s image changed over time is like looking through a window into the major cultural and social shifts of ancient Egypt. He started out as a relatively simple symbol for funerals, but eventually grew into a much more complex god who represented the entire cycle of living and dying. This evolution really shows off how deep Egyptian mythology goes and how it was captured in their art. Basically, understanding these shifts doesn't just teach us about Sokar himself; it also proves how tightly connected art, daily life, and religious beliefs were throughout history.

Work Cited

Abdel–Raziq, A. (2011). Sacred bark of the Bastet. مجلة الإتحاد العام للآثاريين العرب, 12(1), 1-18.

Abt, T., & Hornung, E. (2003). Knowledge for the Afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat-A quest for immortality. Zürich: Living Human Heritage Publications.

Bard, K. A. (2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons.

Biesbroek, A. (n.d.). Sokar. Alexander Ancient Art. https://www.alexanderancientart.com/sokar.php#:~:text=Sokar%20was%20a%20funerary%20god,of%20the%20dead)%20and%20elsewhere.

Broekman, G. P. (2002). The Nile level records of the Twenty-second and Twenty-third Dynasties in Karnak: a reconsideration of their chronological order. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 88(1), 163-178.

Butler, P. (2020, May 5). Sokar. Henadology. https://henadology.wordpress.com/theology/netjeru/sokar/

Chr, Leitz. (2002). Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen. Bd. I− VIII, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, 111, 116.

Dodson, Aidan. (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p.62.

Egyptian texts: Bringing in Sokar (R. O. Faulkner, Trans.). (2023, April 9). Attalus. http://attalus.org/egypt/sokar.html#:~:text=The%20translation%20is%20by%20R.O.,august%20offspring%20of%20%E1%B8%A4ar%2D%E1%B8%A5ekenu!

Esler, P. and Pryor, A. (2020). Painting 1 enoch: biblical interpretation, theology, and artistic practice. Biblical Theology Bulletin Journal of Bible and Culture, 50(3), 136-153.

Gaballa, G. A., & Kitchen, K. A. (1969). The Festival of Sokar. Orientalia, 38(1), 1-76.

Gaballa, G. A. (1972). New Light on the Cult of Sokar. Orientalia, 41(2), 178-179.

Gardiner, A. Η. (1911). The Goddess Nekhbet at the Jubilee Festival of Rameses III. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, 47(1), 225-229. pp. 47 ff.

Geissen, A., & Weber, M. (2007). Untersuchungen zu den ägyptischen Nomenprägungen IX: 15–19. unterägyptischer Gau. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 275-300.

Graindorge-Héreil, C. (1994). Le dieu Sokar à Thèbes au Nouvel Empire. Harrassowitz. p. 239-58.

Graindorge, C. (1996). La Quête de la lumière au mois de Khoiak: Une histoire d'Oies. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 82(1), 83-105.

Griffiths, J. G. (1982). Eight funerary paintings with judgement scenes in the Swansea Wellcome Museum. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 68(1), 228-252.

Hart, G. (2006). A Dictionary of Egyptian gods and goddesses. Routledge.

Habu IV, M. (1940). Festival scenes of Ramses III. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications, 51.

Helck, W. (1956). Untersuchungen zu Manetho und den ägyptischen Königslisten (Vol. 18). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG.

Hill, J. (n.d.). Sokar | Ancient Egypt online. https://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/sokar/

Ivanov, E. 2022. Ancient Divine Ceremonies in the Temples of Egypt. DTTV PUBLICATIONS.

Kahl, J. (2006). Inscriptional evidence for the relative chronology of Dyns. 0–2. In Ancient Egyptian Chronology (pp. 94-115). Brill.

Liu, Y. (2001). Images for the temple: imperial patronage in the development of Tang Daoist art. Artibus Asiae, 61(2), 189.

Liu, Z. (2023). Iconography from a cross-cultural perspective: comparison of expressions in Chinese and European art. AHR, 4(1), 1-11.

Mackenzie, D. A. (2020). Egyptian myth and legend (Vol. 1). Library of Alexandria.

Malek, J. (1997). The cat in ancient Egypt. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 95-97, fig. 62.

Minnick, J. (2021). The Dying Sun: An Iconographical Analysis of the Solar Barque at Sunset in the Cosmological Books of the New Kingdom.

Mironova, V. (2020, July 14). Festival of Sokar (Egypt) - Календарные праздники древнего Востока. Calendars and Festivals of the Ancient Near East. https://anefest.spbu.ru/en/articles/ancient-minor-asia/157-festival-of-sokar-egypt.html#:~:text=The%20festival%20of%20Sokar%20was,of%20Osiris%20killed%20by%20Seth.

Pinch, G. (2002). Handbook of Egyptian mythology. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Pomatto, E., Devecchi, M., & Larcher, F. (2022). Coevolution between terraced landscapes and rural communities: an integrated approach using expert-based assessment and evaluation of winegrowers’ perceptions (northwest piedmont, Italy). Sustainability, 14(14), 8624.

Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. (n.d.). RISD Museum. https://risdmuseum.org/art-design/collection/ptah-sokar-osiris-802621

Redford, D. B. (2002). The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion. Oxford University Press.

Remler, P. (2010). Egyptian mythology, A to Z. Infobase Publishing.

Richter, Barbara A. (2008). "The Amduat and Its Relationship to the Architecture of Early 18th Dynasty Royal Burial Chambers". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 44: 73–104.

San. (2022, January 27). Sokar, Falcon God of the Underworld. Iseum Sanctuary. https://iseumsanctuary.com/2022/01/27/sokar-falcon-god-of-the-underworld/

Schirò, Saverio (9 February 2021). "The Palermo Stone and its Unsolved Mysteries". palermoviva.it.

Schott, S. (1950). Altägyptische Festdaten. Abhandlungen der Geistes-und Sozialwissenschaftlichen Klasse.

Shaw, I. (2003). The Oxford history of ancient Egypt. OUP Oxford.

Shmoop Editorial Team. (2008, November 11). Sokar Sightings. Retrieved December 29, 2025, from https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/sokar/sightings.html

Sokar. (2019). Ancient Egypt: The Mythology. http://www.egyptianmyths.net/sokar.htm#:~:text=(Soker)&text=Sokar%20was%20a%20god%20of,a%20temple%20of%20his%20own.

Stedman, H. (2014). Monuments to the Duke of Wellington in nineteenth-century Ireland: forging British and imperial identities. Irish Geography, 46(1), 129-159. https://doi.org/10.55650/igj.2013.267

Vanhulle, D. (2025). An early ruler etched in stone? A rock art panel from the west bank of Aswan (Egypt). Antiquity, 99(406), 956-972. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.60

Ward, James, with Rob Kuntz (1984). Legends and Lore. TSR Inc. p. 48.

Watterson, B. (2003). Gods of ancient Egypt. The History Press.

Whiting, Nicholas Edward, "The Lost Histories of the Shetayet of Sokar: Contextualizing the Osiris Shaft at Rosetau (Giza) in Archaeological History" (2021). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11693. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11693

Williams, C. (1993). Genres of art history and rationales for and against the inclusion of art history in elementary school curricula: a philosophical study addressing clarification and justification questions regarding art history education. Marilyn Zurmuehlen Working Papers in Art Education, 12(1), 33-42.

Wilkinson, T. A. H. (1999). Early Dynastic Egypt. London-New York: Routledge. p. 260.

Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt

13 Porter, Moss, 1974: 619, plan LXIII (room V); Macramallah, 1935.

14 Porter, Moss, 1974: 524 (room VII).