Comparative Analysis of Land Claims: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives

Executive Summary

Overview and Purpose

Examines how ideas of territorial expansion and inherent superiority have shaped global history, leading to recurring patterns of violence and exploitation. It compares historical precedents—such as European colonialism, 19th-century American expansionism, and Japanese imperialism—with the contemporary geopolitical strategies of modern leaders in the United States, Russia, and China.

Historical Foundations

The Age of Discovery: In the 15th century, Spain and Portugal utilized the doctrine of Terra Nullius and the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) to divide "empty" non-Christian lands between them.

American Expansionism: The 19th-century United States asserted Manifest Destiny as a divine right to spread democracy, while the Monroe Doctrine shifted from a protective stance for Latin America to a justification for U.S. intervention.

Japanese Imperialism: During World War II, Japan used the term Pan-Asianism to cloak its expansionist goals, resulting in significant atrocities such as the Nanjing Massacre and the Bataan Death March.

Core Justifications and Methods

The analysis identifies persistent themes across these eras:

Ideology of Superiority: Expansionist powers often relied on beliefs in racial or national superiority and a "moral duty" to civilize others.

Shift in Methods: While historical claims relied on physical occupation and treaties, modern claims often utilize economic influence (e.g., China's Belt and Road Initiative) and soft power.

Rhetoric vs. Reality: Expansion is frequently framed as a benevolent mission for national security or economic growth, while the underlying reality often involves resource exploitation.

Contemporary Implications

The document highlights current territorial interests, such as:

Strategic Resource Acquisition: Modern interests in regions like Greenland and Venezuela are driven by a desire for natural resources like oil and rare-earth metals.

Resurgent Nationalism: Contemporary "America First" policies and the actions of Russia and China reflect a return to nationalist territorial ambitions.

Conclusion

The essay concludes that while methods have evolved from physical conquest to economic posturing, the core motivations of power and dominance remain unchanged. It warns that following these historical patterns of unilateral expansionism risks escalating into major global conflict.

Introduction and Context

The United States of America, 2026, the government is demonizing everyone who doesn’t agree with them, and I definitely land squarely on that list. The country is already a place where people, we, can get picked up by masked agents while walking or driving down the street, or in our homes. Plus, if not locked away somewhere where no one knows how to find you, you might just be shot in the face, as we saw just a few days ago in Minneapolis.

We are constantly moving into a dystopian novel, if we’re not there already. A healthy dose of 1984 in our lives is just what is needed in our “little” dumpster fire. For those who aren’t aware, 1984 is a novel written in 1949 by George Orwell in the UK. The political fiction novel depicts a forever-at-war totalitarian superstate, Oceania, where the Party, under the eyes of Big Brother through the television screens, could always be watching anyone and everyone, and oversees all aspects of life, thought, and history. It centres on Winston Smith, a minor Party member whose day job is to “unperson” people the Party doesn’t want to exist anymore and who defies the regime by pursuing truth and having a forbidden romance with fellow Party member Julia, which eventually results in his arrest and re-education by the Thought Police.

This book came on the heels of WWII and out of the fear of the rise of totalitarian and fascist states. We have the same fears. We keep getting the pluralisms to WWII and the Nazis, and I completely agree with them, but there’s so much more. For one thing, the abduction of people off the street and in homes sure sounds like Stalin’s Russia to me. Sending people to die out in unsurvivable conditions, has anyone heard about the gulags? Or the atrocities that Japan committed, also during WWII. Or, hell, a more recent example could be the torturous tiger cages that were way too common during the Vietnam War.

But my point is that ideas and actions related to territorial expansion and the belief that one is inherently superior to other human beings have taken many forms throughout history, and they always “end” in violence and death. They’ve been shaped by European colonialism, Japan's imperial plans during World War II, and American ideas such as Manifest Destiny and the Monroe Doctrine. This essay situates these events within the broader context of imperialism and global power struggles, showing how they involved complex reasons, beliefs, and effects that have shaped different eras.

But I don’t just want to go through recent history. I want to go back several centuries, to the time that Trump clearly wants to take the country, and the world, back to. Cause apparently, constant war, racially decided slavery, and genocide are really what make humanity “great”... sarcasm alarm.

Historical Context: The Age of Discovery

The process of claiming land has changed greatly since the Age of Discovery in the 15th century, mainly because you can’t just claim it. When Portugal and Spain led the way, they didn’t care who lived in the land they wanted. As European Christians, they could have whatever they wanted, especially the kings. In the context of today’s politics, the #throwbackthursday every week that modern political leaders like Donald Trump, and the governments of Russia and China, are tagging is the imperialist Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494. This analysis examines the motivations, reasons, and consequences of land claims in the 1400s and compares them with current geopolitical strategies, which often reflect similar themes of territorial expansion and sovereignty.

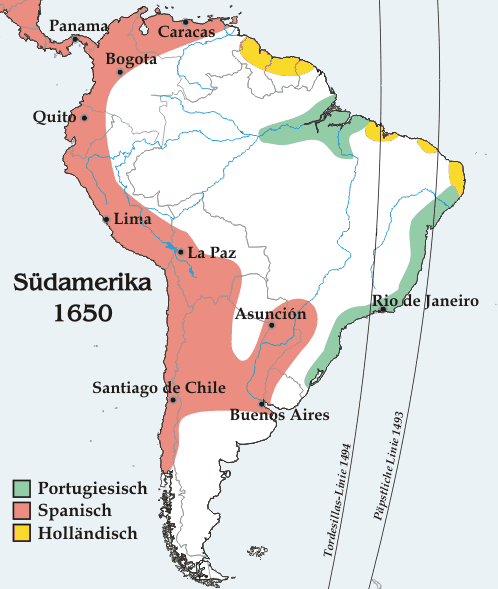

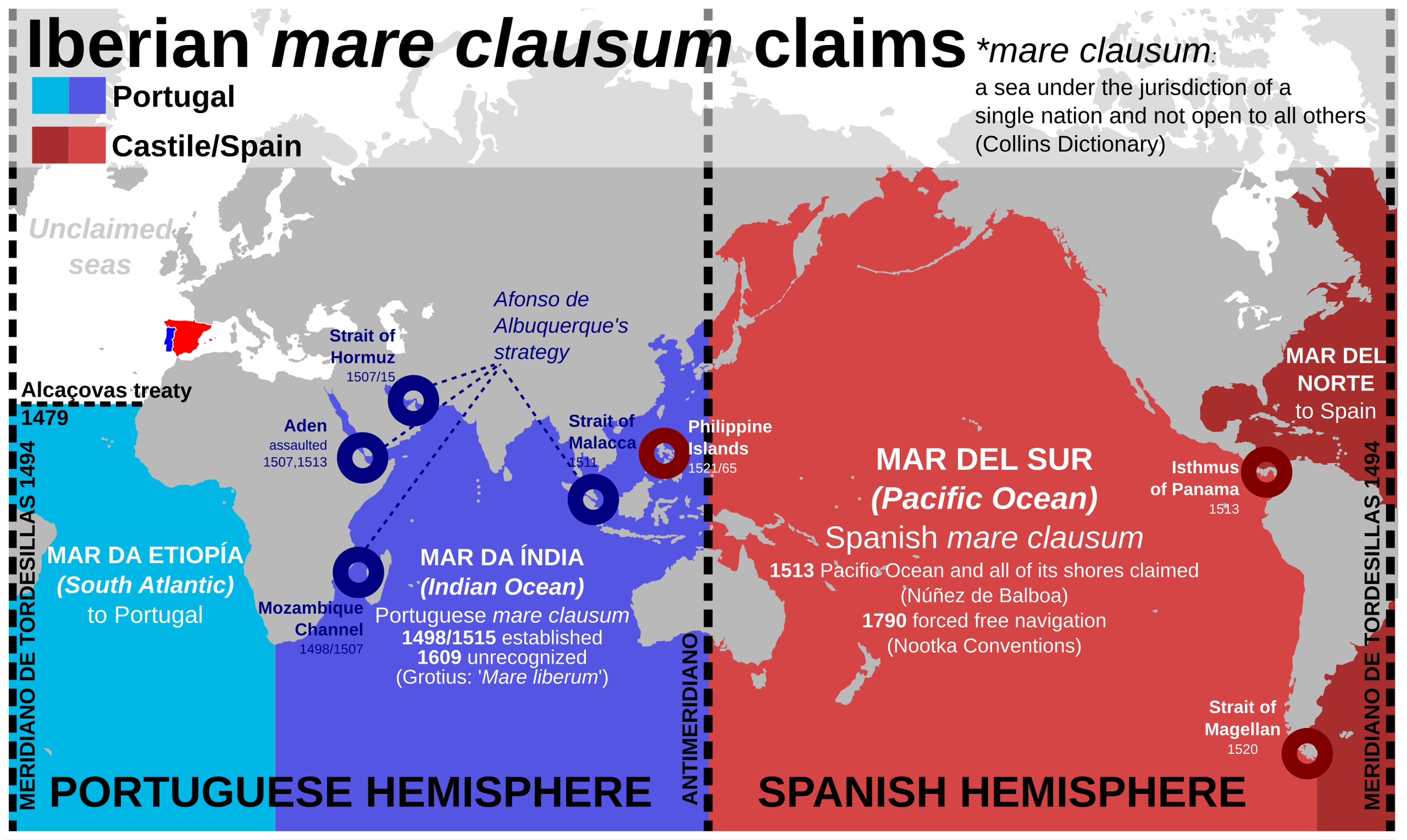

During the 1400s, Portugal and Spain's claims were primarily based in the doctrine of Terra Nullius, which said that lands inhabited by non-Christian peoples could be deemed "empty" and therefore available for Christian nations to claim. The Inter Caetera (meaning: ‘Among other [works]’) Papal Bulls (public decree), issued by Pope Alexander VI on 4 May 1493, granted all lands to the "west and south" of a north-to-south pole line 100 leagues (300 miles, approx. 483 km) to the west and to the southwest of any of the islands of the Azores or the Cape Verde islands to the Catholic Monarchs King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, two kingdoms of Spain. Sanctioned by this declaration, Spanish powers had an (almost) duty to assert sovereignty over non-Christian territories (Figure 1) (Hill et al., 2010).

The following year, in 1494, Portugal’s King John II (João II) became jealous of the land the pope granted to Spain rather than to him; after all, he was also very Roman Catholic. The Treaty of Tordesillas is a clear example of how claims to new lands were formalized through international agreements (Figures 2 & 3) (Tordesillas Treaty, 1494, 2024). It effectively split newly explored territories between Spain and Portugal, as discussed in 'Portuguese-Spanish Interactions in Colonial South America' (2022). This early division was mainly driven by the desire to control resources, establish trade routes, and spread Christianity—motivations that aligned with the economic and religious goals of that period (Miskimin, 1971; Mu, 2023). Plus land and its resources, who wouldn’t want all that?

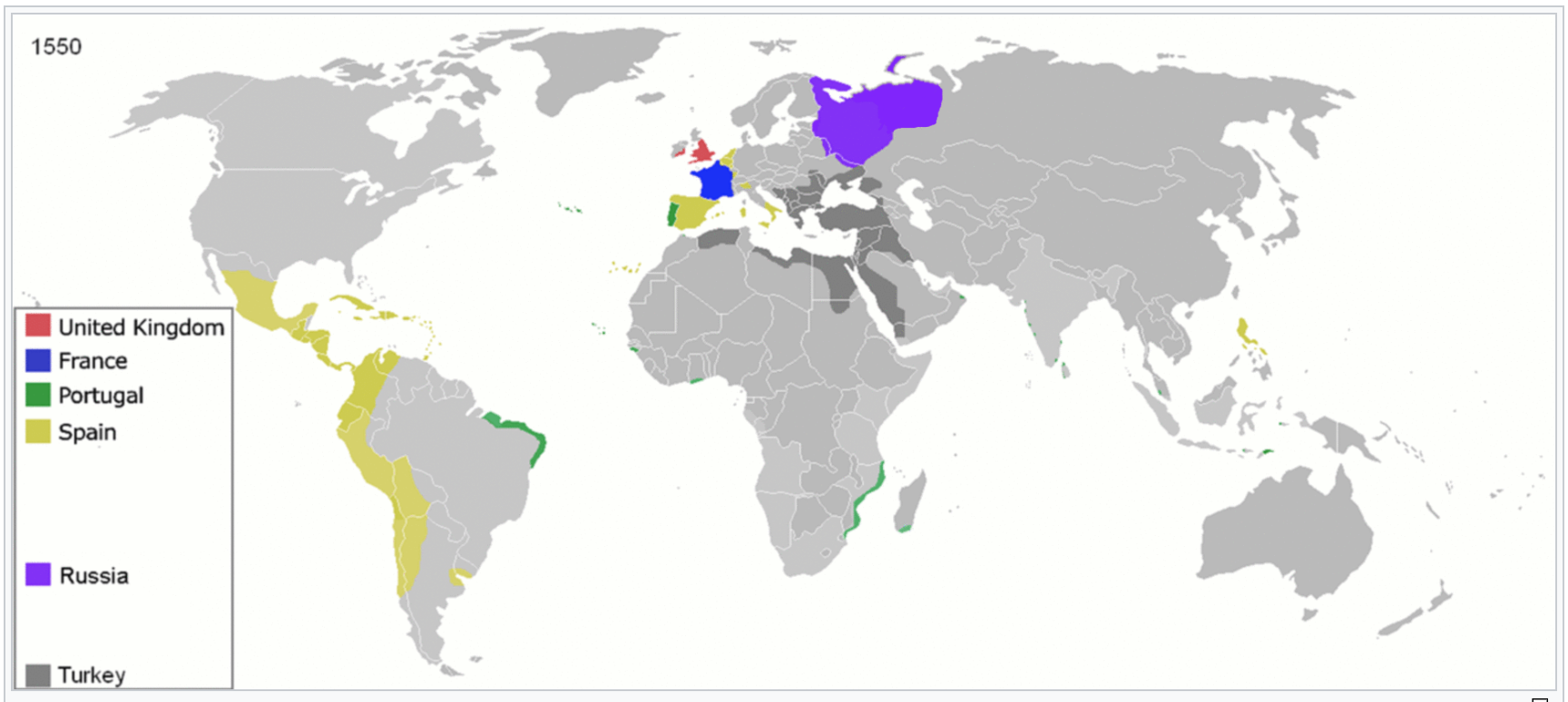

Moreover, this doesn’t even cover the Dutch, English, and French, all trying to carve out a piece of the world, no matter what or who gets in the way (Figure 4: 1500s World map of claimed boundaries). In the United States, we know that, without the English and French colonisation, the US and Canada wouldn’t exist. But using what exists now is no justification for the deplorable nature of what happened in the past. Both countries retained a colonial mindset and acted on it over the next several centuries. But, for this article, I’m going to focus on the US of America side.

American Expansionism: Manifest Destiny and the Monroe Doctrine

American expansionism in the 19th century was characterized by two pivotal doctrines: Manifest Destiny and the Monroe Doctrine. The 20 to 30-year-old country asserted Manifest Destiny, that it was America's divine right to expand its territory across North America, reflecting a sense of mission to spread democracy and civilisation (Costa-Gomes, 2013). This idea was frequently intertwined with racial ideologies, implying a moral obligation to conquer and “civilize lesser civilisations”, and truthfully, the relatively new citizens of the USA just wanted and thought they deserved all the land and resources they could get their hands on (Fraher, 2021).

The Monroe Doctrine, which Trump now wants to rework into his own version, the “Donroe Doctrine,” was first shared in 1823. It was originally a key component of U.S. foreign policy, designed to prevent European countries from attempting to reclaim or reestablish colonies in the Americas. At the time, it was intended as a protective promise to newly independent Latin American nations, reassuring them that they wouldn’t be re-subjugated by European powers (Gilderhus 2006; Loveman 2016). Over time, however, the doctrine came to be used as a justification for U.S. military intervention in the region, sometimes claiming to protect those nations but often serving America’s own expansionist goals. This shift led to U.S. interventions in places like Cuba, Mexico, and other parts of the Caribbean, usually framed as protective actions but really driven by interests in extending U.S. influence and control in the area (Figure 5 - Trump’s map claims) (Dunkerley 2018).

Japanese Imperial Ambitions in World War II

When talking about colonialism, of course, Germany was a huge player in attempting to take over countries using military force. However, Japan's role can't be ignored. World War II is a key example that reflected Japan's expansionist goals. During World War II, Japan's expansion was basically a deluded attempt to take over Asia, cloaked in the term Pan-Asianism. They believed they had a divine right to rule Asia, justifying their military invasions as a means of freeing Asians from Western colonialism and while claiming their own territories (Ali et al., 2023).

Horrible events like the 1937 Nanjing Massacre show this: after taking Nanjing, China's capital, Japanese troops killed hundreds of thousands of civilians and soldiers over six weeks. About 20,000 to 80,000 women and girls were sexually assaulted. They also committed beheadings, buried people alive, set victims on fire, and even bayoneted infants and the elderly (Chan & Felton, 2023). Japan also carried out biological warfare with Unit 731, creating and using weapons like plague, cholera, and typhoid (Donovan, 2024). They dropped infected materials and fleas on Chinese cities, causing widespread disease and death. The Bataan Death March was another nightmare—after taking the Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines, about 75,000 Filipino and American POWs were forced to march 65 miles, with thousands dying from starvation, disease, and brutal treatment (Figure 6) (BBC News, 2015). There were so many more atrocities; this was just an extremely short list of three.

The Japanese military followed a parallel path to what European and American colonial powers had been doing all along, using violence and coercion to carve out their own empire. They went after Korea, China, and Southeast Asia, turning regions into their personal playgrounds of terror. And of course, they wrapped it all up in a nice little story about racial superiority, just like Hitler clung to, harking back to, well, really pre-1492. Despite their elitist attitudes, they still formed alliances with the Axis Powers to maintain their empire in their region, while the European members fought over theirs. They claimed that Western imperialism was all evil and that Japan’s actions were somehow more benevolent. Because nothing says 'benevolent' like brutal conquest (Muniz 2023).

Because of Japan's imperial actions, there were millions of humans and more suffering, so much so that it created long-lasting issues that still influence the relationships between Japan and its neighbors today. There still remain deep-seated negative feelings and tensions stemming from colonial histories that continue to shape diplomatic interactions in East Asia (Karasch 2019).

Comparisons and Contrasts

Justifications for Land Claims

1. Ideology and Belief Systems:

Today’s land claims are often backed by secular ideas like nationalism or economic pragmatism. For example, the Trump administration placed a strong emphasis on "America First" policies, which sought to redraw territorial and trade boundaries from a nationalist perspective. This approach focused more on local pride and economic interests rather than religious or traditional justifications, showing a shift in how land disputes are framed and understood in modern times. But, based on his cozying up with dictators in other countries and not taking care of Americans, whether Democrat, Republican, or MAGA, he’s only putting himself and money first.

2. Legal Frameworks:

Early European claims to new territories were officially recognized through treaties like the Treaty of Tordesillas. This treaty provided a legal basis for dividing newly discovered lands in accordance with the international law of that period ("Portuguese-Spanish Interactions in Colonial South America", 2022; Costa-Gomes, 2013). Today, international laws such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) establish rules for defining territorial waters and economic zones. Nevertheless, these laws are often challenged by powerful nations pursuing their own interests globally, sometimes ignoring established legal frameworks (Miskimin, 1971; Mu, 2023).

3. Justifications and Motives

European colonialism, especially driven by countries like Spain, Portugal, France, and England, was often justified by the belief that Europeans were culturally superior and that there were economic gains to be made. The reasons for colonization frequently included religious reasons and the idea of Terra Nullius, which meant that colonizers could claim lands inhabited by indigenous peoples without truly recognizing their sovereignty, as discussed by Hill et al. (2010) in "Portuguese-Spanish Interactions in Colonial South America" (2022). These justifications were usually presented within a framework that saw colonization as a duty to bring civilization and morality to non-European cultures, implying that it was the moral obligation of European powers to 'civilize' those they considered less developed or different.

4. Impact and Control

Colonialism, as you may rightly assume, caused all sorts of upheaval around the world, cultural, social, and economic. It set up governance systems that pretty much ignored the existing indigenous structures, which left behind a mess of underdevelopment and social conflicts in those colonized spots (Miskimin, 1971). Plus, let’s not forget that the borders drawn and the imperial control exerted created geopolitical tensions that are still around today, affecting international relations for the worse (Mu, 2023).

Methods of Claiming Land

1. Physical Occupation vs. Economic Influence:

Historically, land claims were often based on physical exploration and occupation—that is, people would actually go to the land, explore it thoroughly, settle there, and establish colonies or towns (as noted in "Portuguese-Spanish Interactions in Colonial South America," 2022). These early claims were relatively stable because they involved demonstrating that someone had been there, used the land, and maintained a presence. Moving to more recent times, however, countries like China and Russia have adopted different approaches to territorial claims. Instead of relying solely on explorers or troops, they now invest in the economy—funding projects and building infrastructure—and employ soft power tactics, such as diplomatic influence, cultural exchanges, and subtle persuasion, to sway regions like the South China Sea and Eastern Europe. They tend to assert land claims not through direct military action but by leveraging economic strength, which appears less aggressive but remains effective (Ali et al., 2023; Mu, 2023). Overall, the approach has shifted from physical occupation to a mix of economic and diplomatic strategies that shape territorial claims today.

2. Diplomacy and Conflict:

Colonial powers engaged in serious diplomatic negotiations at various points in history, especially when defining territorial boundaries in regions such as South America (Karasch, 2019). Back then, countries often resolved these borders through formal discussions and agreements. However, today, the situation has changed dramatically. Claims over territories are now more tense and conflicted, and instead of peaceful negotiations, disputes sometimes escalate into military confrontations or standoffs, often without any formal treaties. Recently, we’ve seen this pattern emerge around Taiwan and Eastern Ukraine, where tensions have risen and conflicts have broken out (Mu, 2023). This illustrates a shift from diplomatic talks to more direct and hostile actions.

Comparative Analysis

Although the underlying ideas behind European colonialism, Japanese imperialism, and American expansionism are quite different based on their specific historical contexts, they all share some common themes. One of these is a sense of racial or national superiority, as if they were somehow better or more deserving than others because of the people and culture they were born into. They also tried to justify their actions by claiming they had a divine or moral duty to expand and spread their influence. Both European countries and the United States used language and rhetoric pulling from Christianity that made their expansion seem like a good and civilizing mission. They portrayed their actions as benevolent efforts to help or uplift others, even though, in the vast majority of cases, the reality was the opposite. Behind the scenes, these actions involved exploitation and taking advantage of other peoples and lands, but their public messaging aimed to hide that harsh reality.

Historically, all these powers used cultural stories and narratives to justify their actions. They would often claim that their expansion and imperial ambitions were necessary to improve or uplift the lives of the people they colonized. This helped them rally public support and make their often harsh and brutal methods of control seem more acceptable or justified (Costa-Gomes, 2013). The impact of these expansionist policies was huge, leading to major changes in cultures, politics, and economies across the regions they affected. Even today, many of the tensions and conflicts between countries still trace back to past grievances linked to colonialism and imperialism. The way these old ideas and beliefs continue to influence relationships and disagreements between nations is pretty clear, especially when you look at recent issues involving the United States and its Latin American neighbors (Schwebel, 2011; Vastano, 2023).

Contemporary Context: Claiming Land in 2025 and Beyond

Fast forward to 2025 and 2026, and the geopolitical landscape reflects a resurgence of similar territorial ambitions among certain contemporary leaders, including those associated with Donald Trump’s administration and the governments of Russia and China. These modern claims may not involve physical conquest in the traditional sense yet, but they hinge on strategic economic and military posturing, reflecting a desire for greater influence and regional control (potentially through China's Belt and Road Initiative) (Ali et al., 2023). We can’t escape news about Trump's interest in claiming Greenland because of its “strategic importance” (Ronald, 2026). The only way that Greenland would really help militarily is if we went to war with Europe, which is what would happen if Trump tried to take it. However, the primary reason he wants it is its natural resources, including rare-earth metals, gas, and oil (Ronald, 2026). That last one is really the magic word. That’s why Trump and his cabinet are taking over Venezuela. Why they’re blowing up boats, why he kidnapped their leader, it’s a show of force, to kick out the regime that didn’t want to kiss Trump’s butt and give him everything he wants.

The talk about land claims by today’s politicians still sounds a lot like the old imperialist justifications. They often rely on stories about national security, economic growth, and historical rights to justify their actions. These approaches are similar to the attempts to change borders or take control of resources in disputed areas, much like what happened in South America after Portuguese and Spanish explorers expanded their territories (Muniz 2023, Karasch 2019).

Conclusion

The current geopolitical strategies of figures like Donald Trump, along with the actions of the governments of Russia and China, are heavily influenced by historical themes of territorial claims. These themes are built on a mix of ideology, legal arguments, and power—either military or economic. Looking back, we see examples such as Portugal and Spain claiming land in the 1400s, the United States expanding across the continent, and various European countries and Japan pursuing imperial ambitions during World War II. All of these instances tell a connected story rooted in ideas of superiority and the justification for controlling land. This pattern shows how old beliefs about dominance and control continue to shape how countries interact today. Even though the specific situations and methods have changed over time, the core reasons for seeking to expand territory remain similar, revealing persistent patterns of power and rivalry that have defined international relations throughout history. When Trump gives quotes like ‘it will happen “one way or the other” ’, he is following a dangerous precedent, set hundreds if not thousands of years ago. When rulers conquered their way to power for no one but themselves, the rest of the people suffered for it. Following these patterns, make no mistake, if Trump is allowed to continue doing whatever he wants, we will have another world war. But this time it’ll be the rest of the world against the United States, with no other countries, nor the majority of the country he wants to be king of, coming to Trump’s aid.

References:

(2022). Portuguese-Spanish Interactions in Colonial South America. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199766581-0272

Ali, I., Sulistiyono, S., & Hum, M. (2023). Maritime Heritage and the Belt and Road Initiative: A Historiographical Perspective on Malaysia's Journey as a Maritime Nation. Sejarah, 32(2), 269-300. https://doi.org/10.22452/sejarah.vol32no2.12

BBC News. (2015, August 14). VJ Day: Surviving the horrors of Japan’s WW2 camps. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-33931660#:~:text=Random%20beating%20and%20torture%20was,the%20horrors%20they%20had%20endured.

Chan, A., & Felton, M. (2023, November 9). Why were the Japanese so cruel in World War II? HistoryNet. https://www.historynet.com/a-culture-of-cruelty/#:~:text=Before%20and%20during%20World%20War,Why?&text=On%20Feb.,her%20gently%20toward%20the%20beach.

Costa-Gomes, R. (2013). Portugal. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780195399301-0086

Donovan, J. (2024, June 7). Inside Unit 731, Japan's Gruesome WWII Human Experiment Program. HowStuffWorks. https://history.howstuffworks.com/world-war-ii/unit-731.htm

Dunkerley, J. (2018). 16. US foreign policy in Latin America. https://doi.org/10.1093/hepl/9780198707578.003.0016

Fraher, A. (2021). Psychodynamics of imagination failures: Reflections on the 20th anniversary of 9/11. Management Learning, 52(4), 485-504. https://doi.org/10.1177/13505076211009786

Gilderhus, M. (2006). The Monroe Doctrine: Meanings and Implications. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 36(1), 5-16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5705.2006.00282.x

Hill, J., Lau, M., & Sue, D. (2010). Integrating trauma psychology and cultural psychology: Indigenous perspectives on theory, research, and practice. Traumatology an International Journal, 16(4), 39-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765610388303

Karasch, M. (2019). Riverine Borderlands and Multicultural Contacts in Central Brazil, 1775–1835, 589-612. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199341771.013.23

Loveman, B. (2016). US Foreign Policy toward Latin America in the 19th Century. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.41

Miskimin, H. (1971). Agenda for Early Modern Economic History. The Journal of Economic History, 31(1), 172-183. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022050700094158

Mu, T. (2023). Grand Strategies of Declining Great Powers: Will the United States Become the Next Hegemonic Great Power that Shatters?. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media, 4(1), 769-773. https://doi.org/10.54254/2753-7048/4/2022324

Muniz, P. (2023). The Bishopric of Maranhão and the Indian Directory: Diocesan Government and the Assimilation of Indigenous Peoples in Amazonia (1677–1798). Religions, 14(12), 1515. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121515

Ronald, I. (2026, January 8). Why Does Trump Want Greenland and Why Is It So Important? CNN. Retrieved January 9, 2026, from https://www.cnn.com/2026/01/06/europe/why-trump-wants-greenland-importance-intl

Schwebel, M. (2011). Victories over structural violence. Peace and Conflict Journal of Peace Psychology, 17(1), 85-99. https://doi.org/10.1080/10781919.2010.535138

Tordesillas Treaty, 1494. (2024, November 17). Memory of the World - Latin America and the Caribbean. https://www.unesco.org/en/memoryworld/lac/tordesillas-treaty-1494#:~:text=The%20Tordesillas%20Treaty%20of%20June,of%20the%20Cape%20Verde%20Islands.

U.S. Marine Corps. (accessed 13 January 2026). Bataan Death March. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Bataan-Death-March/images-videos#/media/1/55717/250238

Vastano, A. (2023). The Hypocrisy of the Monroe Doctrine. The General Brock University Undergraduate Journal of History, 8, 209-220. https://doi.org/10.26522/tg.v8i.4200

Figure 1. Map of South America; the meridian to the right was defined by Inter caetera (1493), the one to the left by the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494). Modern boundaries and cities are shown for purposes of illustration. (Attribution to Wikipedia User Tzzzpfff under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Figure 2. Iberian 'mare clausum' ('closed sea') claims during the Age of Discovery from 1479 to 1790. Base map source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blank_Map_Pacific_World.svg (Made by Wikipedia user Nagihuin under CC BY-SA 4.0).

Figure 3. By Unknown author - Pieced together from Biblioteca Estense, Modena, Italy, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2328448

Figure 4. The territories of colonial empires in the 1550s (Made public domain by Wikipedia user Urnanabha

Figure 5. Land Claims in the Western Hemisphere that Trump has made (Made by Renée Whitehouse using base map: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_expansionism_under_Donald_Trump#/media/File:Greater_USA_(+Canada+Greenland+Panama_Canal_Zone).svg by Nagihuin under CC BY 4.0

Figure 6. American survivors of the Battle of Bataan under Japanese guard before beginning the Bataan Death March. (Attributed to US Marine Corps. from Encyclopædia Britannica, accessed Jan 13 2026).