Mythic Breakdown of The Raven

There’ve been way too many synopses and examinations of the text of “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe. So I don’t know if this will say anything particularly new, but they’ll follow my archaeological bent. So let’s follow the raven through the chamber door.

Figure 1. "The Raven" depicts a mysterious raven's midnight visit to a mourning narrator, as illustrated by Édouard Manet (1875), digitally restored.

The Raven was written in 1844-45 and published in 1845 by Edgar Allen Poe. The story within the story takes place in the dead of winter, a “bleak December,” which may be a connection to the end of the year based on the use of "midnight" in the first verse and "December" in the second verse. Both midnight and December symbolise the end of something, as well as the anticipation of something new, a change, to happen. According to Swedish computer scientist and writer Christoffer Hallqvist (1998), the midnight in December could be New Year’s Eve, a date most of us connect with change, which also seems to be what Viktor Rydberg believes when he is translating “The Raven” to Swedish, since he uses the phrase “årets sista natt var inne,” (“The last night of the year had arrived”). Though I suppose it’s more of a Christmas ghost story, much in the vein of A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, which was published two years earlier, in 1843. This was back when the seasonal traditions had a stronger connection to the liminal spaces in a time of year when the veil between worlds is thin, and following in those footsteps, The Nightmare Before Christmas. It was a common tradition to tell ghost stories in the 1800s and before, especially during the Victorian Era, when the tradition was shared with America, particularly in New England, where Poe was writing. The Raven was published in January 1845 to instant success in the New York Evening Mirror. I don’t know why I ever thought this, but “the lost Lenore” wasn’t based on Poe’s child bride, Virginia Eliza (Clemm) Poe, who was 13 years old when she got married to her 27-year-old first cousin -blehh-. This was because she hadn’t died yet. Eliza actually died of tuberculosis two years after "The Raven" was published in 1845. And two years later, Poe, unfortunately, died mysteriously.

I slightly wonder (highly doubt any truth of it) if this poem was about his mother, who passed when Edgar was only two (Stashower 2006: 35). It is commonly believed that she died of tuberculosis at the age of 24, just like Edgar’s wife. Same age, same disease, same names, well, sort of. His mother was called Eliza, for Elizabeth, and Virginia’s middle name was Eliza. Coincidence..? Probably. He could have just been writing about death in general; it wasn’t uncommon. But his mother’s death was thought to have inspired Poe’s writing about lost women (Weeks 2002). The loss of a loved one that the audience could connect with. Or maybe he had a first love that either broke his heart or died, so either option was the “nameless… evermore… that the angels name Lenore”. Additionally, Lenore rhymes with evermore, making it a suitable choice for poetry.

The specific mention of the purple curtains at the window could be an illusion of the royal color, especially in Greece and Rome, the same place where much of the “forgotten lore” that Poe uses comes from. It may not be particularly meaningful, but they set the stage for the rest of the nameless narrator’s tale. The dive into Greek and Roman mythology was pretty prevalent at the time. It was still relatively recently after the Renaissance when the Classics were all brought back into the zeitgeist, studied, and enjoyed for all the inspiration they could muster.

After a time of rapping and tapping at the chamber door, the narrator opens it to darkness and whispers Lenore. The whisper is clearly a wish that a ghost was really there, but upon the “echo” answering, the narrator goes into full denial, “merely this and nothing more”.

The lattice is a design in walls, fences, garden trellises, and windows that would mean specific things for and based on the community where they were built. (For more examples, see the 3-part episode series on lattice work from various cultures around the world.) In Greece and Rome, the lattice design was connected to mythological brothers Castor and Pollux, who would move from the world to the underworld and back, and their sister Helen of Sparta (of Troy). The connection between the siblings became a backdrop and witness for contracts that the other gods would preside over to make sure the swearers are telling the truth and will keep their oaths. Which is something that the character wants after the echo repeated, almost confirming, at least in his hopeful mind, that the voice was Lenore.

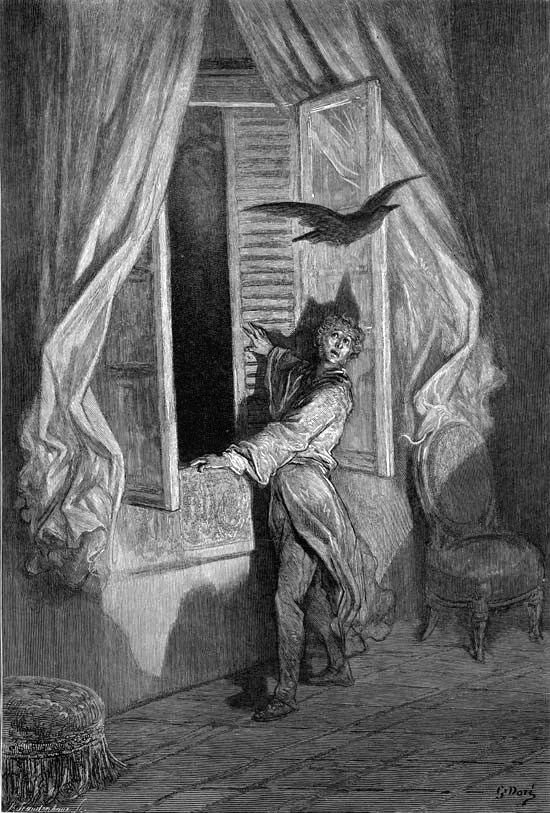

Figure 2. "Not the least obeisance made he" (7:3), as illustrated by Gustave Doré (1884).

Interestingly, the narrator gendered the raven as a he, especially if he wanted it to be Lenore. But it’s not like he could really tell what gender the bird was by looking at it. Unless Poe was saying that the narrator was an experienced ornithologist (they don’t have dicks just hanging down).

The line “of the saintly days of yore” makes me think of Hamlet…

Figure -3 Athena Pallas Giustiniani´s bust

Figure 4. Bust of Pallas Raven Edgar Allan Poe Dictionary Art Print Picture Statue Athena by blackcatz_artprints

The raven didn’t seem to have any respect in the character’s room and flew around the chamber and it sat upon the bust of Pallas. Pallas refers to Pallas Athena, with the name "Pallas" being an epithet, and there are several myths explaining the connection, most notably that she accidentally killed her childhood friend Pallas, a nymph, and adopted her name out of grief. Alternatively, Pallas was a giant whom Athena defeated, taking his skin for her shield, or a warrior whom she vanquished to earn the name. The name itself is often associated with wisdom, strategy, and warfare, so "Pallas Athena" represents the goddess's prowess and strategic power.

More details on the explanations for the epithet "Pallas" include:

Figure 5. Cassandra clutches what is perhaps meant to be the Palladium, a wooden statue in the image of Athena or, alternatively, a statue made by Athena that represents her friend Pallas. The Lesser Ajax is trying to drag her away, while her father despairs. Roman fresco from the atrium of the House of Menander in Pompeii. (from “Who’s Pallas? Or: Greek mythology is a mess” by Josho Brouwers 2019)

The friendship with the nymph Pallas, the daughter of Triton, who was raised with Athena. During a sparring session, a childhood war game, with Zeus watching them, Athena, trying to dodge Pallas, accidentally impaled her friend with a spear, killing her. In her grief, Athena created a wooden statue of her friend, known as the Palladium, which she later honored and used as a protective artifact. She wrapped the aegis, a cloak that she feared, around the statue and placed it beside a statue of Zeus, honoring her lost friend. The Palladium became a sacred object, later kept in the city of Troy to protect it. Another explanation of the epithet was the defeat of the giant Pallas. In this myth, Athena slew a giant named Pallas during the Gigantomachy (a war between giants and gods). She then flayed him and used his skin as a shield or a war cloak. The giant during this war that Athena was celebrated for killing, however, was Enceladus (Enkelados), the Giant of Mount Etna. Or Athena fought and defeated Pallas the Titan, who was associated with war, from whom she supposedly made the aegis breastplate from his skin for her armor to which she later added the head of Medusa.

Figure 6. Athena (left) fighting Enceladus (inscribed retrograde) on an Attic red-figure dish, c. 530 BC (Louvre CA3662).

"Pallas" may derive from the Greek verb pallô, meaning “to brandish (a spear)”. In this sense, "Pallas Athena" can be interpreted as “Athena who brandishes the spear,” a title that fits her role as a warrior goddess. Otherwise, the name Athena, also known for her craftsmanship, is combined with an epithet meaning “youth” or “young woman.” The combined name symbolises wisdom, particularly feminine wisdom, independence, strategic warfare, and defensive arts.

[The Vienna Secession art movement adopted Pallas Athena as a symbol because they saw themselves in a state of "war" with traditional European art, using intelligence to gain the upper hand.]

The representation of wisdom, reason, and scholarship has been exhaustively discussed and the titular raven landing on the bust symbolizes the descent of despair over reason and sanity (Rationality and Irrationality Theme in the Raven | LitCharts, n.d.). Where the bust stands for a rational mind and the attempt to use logic to understand what is happening. Because the raven never leaves the bust, the argument has been made that the narrator's mind is permanently taken over by the irrationality of grief, crushing his ability to ability to think logically (Rationality and Irrationality Theme in the Raven | LitCharts, n.d.). However, in the majority of cultures around the world, the raven is a wise character, sometimes a trickster, sometimes a hero to mankind, often a messenger between the world and the afterlife, but always a representation of knowledge, likely because of their actual intelligence. While Athena’s animal symbol was the owl and Apollo’s was the raven/crow the raven still matches well with the symbolism and myths of Athena.

The bird was “shorn or shaven”, so dishelved, though the narrator mentions that it was “no craven”, meaning that it wasn’t a coward.

The “Night’s Plutoian shore” refers to the Roman underworld, which is ruled by the god Pluto, as known as Hades in Hades to the ancient Greeks. In the mythology, the deceased must cross the Rivers Styx and Acheron, the “river of woe”, first to be crossed, by the ferryman Charon (Rivers of the Underworld, n.d.). The soul had to pay Charon a coin, typically an obol or Persian denarius, which had to be placed in the mouth of the deceased before burial. While neither coin was particularly valuable, it meant that the deceased had been given the proper funeral rites. The consequences of not paying were that the souls would be denied passage, and they were cursed to wander the riverbanks for 100 years (The Ferryman Charon in Greek Mythology, n.d.).

But those were only two of the five rivers around the underworld; the others are the Cocytus, “the river of lamentation/wails” that flows through Tartarus. The Phlegethon, the river of “fire” or the “flaming river”, which was described by Plato as a stream of fire that coils around the earth and flows into the depths of Tartarus. In some myths, it is said that the river literally flows with fire and is associated with punishment for the wicked or the eternal torment of those who committed violence, while in other versions, the river can burn away a person's sins by drinking it or being dunked in, especially if the person was truly remorseful. In Dante's Inferno, it is a river of boiling blood that punishes violent offenders, with the depth of their submersion determined by the severity of their crime. (Greek Mythology Places, n.d.; Alighieri 2009, Phlegethon: Circle 7, Inferno 12). The final is Lethe, the “river of forgetfulness”, where souls drink to forget their past lives before being reborn (Rivers of the Underworld, n.d.).

According to the Achilleid, written by the Roman poet Statius in the 1st century CE, when Achilles was born his mother Thetis tried to make him immortal by dipping him in the river Styx; however, he was left vulnerable at the part of the body by which she held him: his left heel, so Paris was able to kill Achilles during the Trojan War by shooting an arrow into his heel (Burgess: 9; Statius, Achilleid 1.133–134, 269–270, 480–481). Although comparing that with Hyginus’s Fabulae (107), which says that Achilles' heel "was said to be vulnerable" but made no mention of being dipped in the river Styx.

Figure 9. 4th-century relief with the life of Achilles, cropped; scene where Thetis dips him as a baby into the river Styx. Museum of Eleutherna, Crete, Greece.

The goddess Styx, like her father Oceanus and his sons, the river gods, was also a river. According to Hesiod, Styx was given one-tenth of her father's water, which flowed far underground until it came up to the surface to pour out from a high rock. The River Styx makes another connection to oath-making and -keeping, as it was not only the main river souls had to cross to reach the underworld, but it was also known as the river of unbreakable oaths by which the gods swear. This is because the goddess Styx helped Zeus during the Titanomachy and became the goddess of oaths (Hesiod, Theogony: 785–789). The gods swore their most sacred oaths by her waters, and violating such an oath resulted in severe punishment.

I suppose that any of the shores that lead to the underworld would work, because Poe is not specific, as the narrator is calling the bird a messenger from Pluto’s underworld in the general sense. Either the raven said its name was Nevermore, as the narrator assumes, or is it just saying “no”, or maybe that even if it’s from the Plutoian Shore. Maybe all names are ‘nevermore’ because they are nevermore said due to the drink or dip into the River Lethe, thus no one has names anymore.

In the text, the narrator said, “Though its answer little meaning-little relevancy bore”, but how would he know what is relevant to his question? He doesn’t know what happens after death, especially since, presumably, the narrator would have been an ‘intellectual Christian’ as he is distinguishing everything in terms of the Classics, which seemed to give him a more solid connection to the world around him, at least until now. Obviously, I cannot dig into the mind and motives of a fictional character, or even the mind of Poe, so I’m not sure what they are thinking. Especially wondering why the narrator would feel blessed by having a bird or beast perched on a “sculptured bust above his chamber door”, whether or not it had the name of Nevermore.

As the narrator is getting sick of the bird's presence, he says that the bird was taught what word to say by “some unhappy master”, who most likely died, hence the dirges after the “unmerciful Disaster” force continuously followed the master. “Stock and store” was basically an insult at the supposed canned response that had no meaning. At first, the narrator is trying to understand the raven, but can’t deal with the bird’s irrational answers (Rationality and Irrationality Theme in the Raven | LitCharts, n.d.). The narrator is frustrated because he is constantly anthropomorphising the raven and reading intent into everything it does, which leads him to feel hurt when it acts human and then angry when it continues its chill bird behavior. Even though he’s still angry, if the bird leaves in the morning, he knows he’ll be in a deeper depression, because he will be abandoned once again. Though it’s the same canned response, the narrator’s mood still substantially lightens as if the narrator thinks the bird could say anything else.

The narrator moves his chair closer to the door to delve deeper into what the raven’s intentions were and the specific meaning of nevermore. It, of course, gave no responses and the air seemed to grow heavy in the silence. The narrator could imagine that an invisible Seraphim, an angel of the highest order in some mythologies, carrying around a censer. The etymology of the word Seraphim, according to Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, was that it came from a word meaning “those who kindle or make hot” ("Celestial Hierarchy"). They are often depicted in Christian artworks as humans with 3 sets of bird-like wings facing different directions. But using the original etymological source, further descriptions said that the all-fire Seraphim are “dispelling and destroying the shadows of darkness” ("Celestial Hierarchy"). Of course, this may be literal fire or, as Thomas Aquinas wrote in the Summa Theologiae, it’s the properties of fire that Pseudo-Dionysius was talking about. That, because those angels are born with an “inflexibility towards God” since they, like fire, are always going up. Second, that the heat itself is a “penetrating action…rousing…and cleansing them by their heat”. And third, that the angels have an inextinguishable light or brightness and clarity, so they would enlighten others. (Thomas Aquinas 1952).

The Seraphim also appear in Jewish and Islamic texts, but as Poe was raised in a predominantly Christian run country, and not being either other religion himself, while he may have read some of the texts he probably wouldn’t be as familiar with them or pictured the Seraphim in their zoomorphic forms, with the head of a bull, an eagle, a lion, or a human or with the more common six wings, but four faces as they are depicted in Islamic texts (Burge 2015: 265). Or, in Jewish texts, as fitting into the mid to top of the angel hierarchy, constantly burning up before reforming in their proper place because they got too close to God. They have also been depicted as flying asps (snakes) with human characteristics in a Judean seal from the 8th century BCE (Berlin et al. 2014: 779). The swinging censers were to bless and cleanse the space, as they still do before or during Catholic mass, with the same purpose as when people do and have done with sage and incense for millennia.

The phrase “tinkled over the tufted floor” is funny to me, but I guess it makes sense because they don’t have to walk at all with their wings; they’re choosing to use both just to be extra. And the narrator claims that God sent the raven with angels in his mind. To be fair, the raven is most likely in his mind too; it doesn’t eat or poop once. He just begs them all to be rid of the memories of his lost Lenore.

The nepenthe is another Classical illusion, as it alludes to Homer’s Odyssey. Figuratively, it means “that which chases away sorrow” and literally means “not-sorrow” or “anti-sorrow”. In the classic Greek mythology, nepenthe was used as an epithet for Apollo, which also connects to ravens, as they were one of his sacred animals. Nepenthe was also a drug, said to be from Egypt, that was used by Helen of Troy/Sparta (a call-back to the lattice design and making oaths) while she was still held captive in Troy. She grabbed the drug she received from Polydamne, wife of “Egyptian Thon”, and threw it into the wine that her once and present husband, Menelaus, and Odysseus’s son Telemachus were drinking (Homer Odyssey Book 4: v219-221; v228). Not out of malice, she wanted them to forget the pain of losing their life-long friend and father before regaling both of them with the story of when Ody snuck into Troy and saved her by killing heaps of Trojans (Homer Odyssey Book 4 v264). Hoping that the angels will give him such a drug, the narrator is desperate to forget his heartbreak.

When the raven continues to reply in the negative, the narrator gets pissed and speaks multiple verses, or rather shouts at the bird, calling it a devil, asking whether it was indeed sent by God, by Satan the tempter, or if a huge storm (a tempest) washed it ashore. The next question he asks is if there is “balm in Gilead”. Gilead is a mountainous region east of the Jordan River in Northern Jordan, where a famous medicinal balm/perfume was made from the Commiphora gileadensis. It’s referenced in the Old Testament and is really sold and used to reduce skin irritations, relieve muscle and joint pain, and comfort respiratory issues. In the Hebrew Bible (Torah), it also took on a metaphorical meaning, symbolizing spiritual healing for Israel and sinners, though the phrase is now used as symbolism for a universal cure or a source of hope and healing. It could also allude to the peace treaty that Jacob and his father-in-law, Leban, reached at the location which led to the name Gilead, meaning heap or cairn of witnesses. So the narrator is either pleading for spiritual healing, for peace, for an ease of pain or it’s embodiment of the raven.

In the next stanza, the narrator, still desperate for an answer, asks the raven if he and Lenore will be reunited in Paradise, as the name Aidenn is the Arabic and biblical name for Eden, as in ‘the garden of’. Hoping the afterlife will give his respite, but the only word spoken is still and will always be “nevermore”.

Figure 19. Distant Aidenn by Gustave Doré 1884

By the end, the narrator is sick of the bird and wants it to return from the storm that carried it or the underworld as its messenger, leaving the statue of wisdom after imparting none. The phrase "from out my heart," Poe claims, is used, in combination with the answer "Nevermore," to let the narrator realize that he should not try to seek a moral in what has been previously narrated (Poe, 1850). But it won’t end and the shadow that the raven casts over the room envelopes the narrator into his own darkness and sorrow, forevermore.

Figure 20. Gustave Doré's illustration of the final lines of the poem accompanies the phrase "And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor/Shall be lifted—nevermore!"

Figure 21. The original grave of Edgar Allan Poe before he was reburied.

Citations

Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi; and Jewish Publication Society. (2014).The Jewish Study Bible Jewish Publication Society Tanakh translation. New York, New York : Oxford University Press. p. 779.

Burge, Stephen (2015). Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi Akhbar al-malik. Routledge. p. 265.

Dante, Inferno, in The Divine Comedy of Dante, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (translator), Kessinger Publishing (2004).

Dionysius the Areopagite. "Celestial Hierarchy"

“Greek mythology places”. (n.d.). https://www.desy.de/gna/interpedia/greek_myth/place.html#:~:text=Geographically%2C%20the%20underworld%20is%20surrounded,Lethe%20(river%20of%20forgetfulness).

Hallqvist, C. 1998. The Poe Decoder - “The Raven.” Poe Decoder. https://www.poedecoder.com/essays/raven/#:~:text=The%20raven%20perched%20on%20the,Shall%20be%20lifted%20%2D%2D%20Nevermore!%22.

Hesiod. Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. 1914. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

Kopley, Richard and Kevin J. Hayes. "Two verse masterworks: 'The Raven' and 'Ulalume'", collected in The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Kevin J. Hayes. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Poe, Edgar Allan. "The Philosophy of Composition." http://www.poedecoder.com/Qrisse/works/philosophy.php, 1850.

Stashower, Daniel. 2006. The Beautiful Cigar Girl: Mary Rogers, Edgar Allan Poe, and the Invention of Murder. New York: Dutton.

Rationality and irrationality theme in the Raven | LitCharts. (n.d.). LitCharts. https://www.litcharts.com/lit/the-raven/themes/rationality-and-irrationality#:~:text=Even%20after%20he%20meets%20the,from%20a%20previous%20unhappy%20owner.

Rivers of the Underworld. (n.d.). Greek Legends and Myths. https://www.greeklegendsandmyths.com/rivers-of-the-underworld.html

“The Ferryman Charon in Greek Mythology” (n.d.). Greek Legends and Myths. https://www.greeklegendsandmyths.com/charon.html#:~:text=Charon%20the%20Ferryman&text=Here%20the%20skiff%20of%20Charon,found%20in%20the%20Greek%20underworld.

Thomas Aquinas (1952), edd. Walter Farrell, OP, and Martin J. Healy, My Way of Life: Pocket Edition of St. Thomas—The Summa Simplified for Everyone, Brooklyn: Confraternity of the Precious Blood.

Tolentino, C. (2025, February 3). Pallas: The Titan God of Warfare and Wisdom in Greek mythology | History Cooperative. History Cooperative. https://historycooperative.org/pallas/#:~:text=Nymph%20Pallas%20is%20a%20daughter,Pallas%20Athena%E2%80%9D%20in%20her%20honor.

νηπενθές. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

Weekes, Karen. 2002. "Poe's feminine ideal", collected in The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Kevin J. Hayes. Cambridge University Press: 149.