Hathor ²: What is Love?

Figure 1. Hathor, ancient Egyptian goddess. Hathor is depicted in many forms, most commonly as a woman with cow-horns and sun disk. Isis could also be depicted in this form, and the two can only distinguished by the inscription. Hathor is often shown holding the was scepter. This image is partially based on images of Hathor from the tomb of Nefertari, and can also represent other Goddesses with similar iconography like Isis, Iunit, Raet-Tawy, Iusaaset, and Nebethetepet. (Figure from PharaohCrab).

Hathor is one of the most prominent ancient Egyptian goddesses. One of the 42 state gods and goddesses, revered as a deity of love, beauty, music, dancing, joy, pleasure, fertility, and motherhood. She is also a sky goddess and is associated with the afterlife along with many more godly aspects. She is often depicted as a cow or a woman with a cow's head or horns. In fact, because of Hathor’s connections to beauty, inside and out that it was a great compliment if someone was called a ‘heifer’ — a young female cow who has not given birth (and yes, I looked that up).

We-eeeell… that word in itself would not have been used, I dove into an etymology rabbit hole, and there are so many disputes:

Middle English heifer, from Old English heahfore (West Saxon); Northumbrian hehfaro, heffera (plural), but "heifer," of unknown origins, not found outside English.

The first element seems to be heah "high," which is common in Old English compounds with a sense of "great in size." The second element might be from a fem. form of Old English fearr "bull," from Proto-Germanic *farzi-, from PIE root pere- (1) "to produce, bring forth." Or it might be related to Old English faran "to go" (giving the whole a sense of "high-stepper"); but there are serious sense difficulties with both conjectures. Liberman offers this alternative:

Old English seems to have had the word *hægfore 'heifer.' The first element ( *hæg-) presumably meant 'enclosure' (as do haw and hedge), whereas -fore was a suffix meaning 'dweller, occupant' ....

In modern use, a female that has not yet calved, as opposed to a cow (n.), which has, and a calf (n.1), which is an animal of either sex not more than a year old. As derisive slang for “a woman, girl”, which dates from 1835.

(from Etymology.com)

But I haven’t seen it traced back further, this is important, or interesting rather, because as the “self taught Egyptologist” Nicole Lesar shares on Instagram (ancient egypt blog Instagram) the Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs for cow “𓄤𓆑𓂋𓏏𓃒” and for “beautiful woman “𓄤𓆑𓂋𓏏𓁐” are the same other for the very last symbol, which signifies which creature the writer is symbolizing about (yes, humans are creatures, fight me). In her post, she continued that

“The root of both of these words is “𓄤𓆑𓂋” which would probably be pronounced like “nefer.” … [which] could mean perfect, beautiful, or good in Middle Egyptian! Adding the “𓏏” to the end of the word makes it feminine, and then the determinative symbol distinguishes the meaning! So “𓄤𓆑𓂋𓏏” could also mean a beautiful woman or beautiful/perfect! Both “cow 𓄤𓆑𓂋𓏏𓃒” and “beautiful woman 𓄤𓆑𓂋𓏏𓁐” would have probably been pronounced like “neferet” due to the addition of the uniliteral phonogram of “𓏏” which would have been pronounced like a “t.” In order to make words pronounceable in modern times, a lot of Egyptologists/linguists will add a soft “e” sound in between the consonants!”

Another piece of validation for this is that Nefertiti (the great queen, wife of Akhenaten, and mother of King Tut), her name means “the beautiful one (has arrived)”, according to researchers. In addition, Nefertari (queen and Rameses II’s wife), who’s name means “beautiful companion” So, in my mind, it seems obvious that “nefer” means beautiful and would work as a compliment for a beautiful woman or girl, and could have easily been transliterated at some point into hefer (which is how it’s pronounced anyway, not “high-fer” or “hee-fer”… Although we don’t actually know what the vowels were that the Ancient Egyptians did not write in their texts, the first sound could easily have been the “hi” or “hee” sound (even though archaeologists and Egyptologists are fairly certain they know it’s the other way).

— My name is Renée, welcome to Detours in Artaeology, this is Hathor <squared>: what is love? (Woah woah woah woooah) —

Role:

She is a goddess of love, beauty, music, and dance, but also of motherhood, fertility, and protection, particularly for women. Hathor was also considered a guide and protector of the deceased, welcoming them to the afterlife.

For a more detailed look at Hathor:

(Ancient Egyptian: ḥwt-ḥr, lit. 'House of Horus', the hieroglyph for her name is a square with a falcon inside it.

The literal meaning of the name ‘Hathor’ is the ‘house of Horus.’ Scholars and historians have interpreted this name in various ways. One of the popular interpretations is that Hathor was the mother of Horus, with ‘house’ meaning ‘womb.’ Even though the general myth states that Isis and Osiris are the parents of Horus (after some falcon schenanigans*), after which Hathor is the adoptive mother and protector of Horus from Set. Some, however, interpret this as Hathor being the wife of Horus, rather than his mother, and as the consort of the pharaoh's embodiment. Hathor became associated with royal wives, particularly with the king’s chief wife, who became her priestess. However, it could also mean ‘sky goddess’ since the sky is where the falcon resides (which she has often been interpreted as one). Her name was also supposed to refer to the royal family, whose mythical mother she was through Horus.

In Ancient Greek, the name was transliterated as Ἁθώρ Hathōr, in Coptic ϩⲁⲑⲱⲣ, and in Meroitic as 𐦠𐦴𐦫𐦢 Atari (Hart 2005, p. 61). So again, we get the pronunciation of the name from Greek <but I don’t think I could pronounce it right ever at all during the podcast, so (sorry for Apep), but Hathor will stay Hathor the entire time.

But she had many names or epithets…

The Primeval Goddess

Lady of the Holy Country

Lady of the West

The Foremost One in the Barque of Millions

Lady of Stars

Lady of the Southern Sycamore

Hathor of the Sycamore

Hathor of the Sycamore in All Her Places

Hand of God

Hathor, Mistress of the Desert

Hathor, Mistress of Heaven

In the Sinai turquoise mines, she was called “Lady of Turquoise.”

While some of these titles are clear enough, some of the others are not as obvious. As the goddess of motherhood and childbirth, she was called the ‘Mother of Mothers.’ As the goddess of sexuality and dance, Hathor was called the ‘Hand of God’ or ‘Lady of the Vulva.’ These were both supposed to refer to the act of masturbation, which provides us with an interesting view into the minds of the ancient Egyptians. (Dhar 2024).

Her temple was called the "home of intoxication and enjoyment" (Larousse Encyclopedia, 25), linking her to alcoholic drinks featured in her festivals and shown on wine and beer vessels. Hathor was also a funerary goddess. Egyptians sought her protection in the afterlife, known as the Lady of the Sycamore (as mentioned above), welcoming the dead with food and water, and as Queen of the West she guarded the Theban cemetery. She was also the goddess of foreign lands, protecting trade and precious resources from regions like Lebanon and Punt (a land that Hatshepsut traded with, but we don’t know where it is in the modern day).

Domains and Roles

As is fairly obvious from the various stories above, Hathor had many roles and attributes. Many of these contradict each other and still seem to work together. She was not a deity who seemingly had a minor domain but was actually the preeminent goddess for the early Egyptians. She played a role in the lives of all people, from birth right up to the afterlife.

Sky Goddess

The ancient Egyptians thought of the sky as a body of water and the place from which their gods were born. As the mythological mother of the world and even of some of the other gods, Hathor was called the ‘mistress of the sky’ or the ‘mistress of the stars.’ In some Egyptian representations, she appears as a sky goddess holding up the sky, with her legs forming the four pillars that support it.

She was represented as a heavenly cow in this form. This Hathor-cow form gave birth to the sun and placed it in her horns every day. Which, interestingly enough, was Nut’s duty in many other stories, giving birth to the sun and moon each day and night, as shown in the second intermediate period’s rock-cut tombs (Tomb Art).

Figure 2. Hathor (as milk filled cow), aka House of Horus, is the origin of the name "Milky Way" (posted by JohannGoethe)

Sun Goddess

Regarding Hathor, Horus, and Ra, their familial relationships are unclear, with no definitive knowledge of who was born from or fathered whom. Hathor served as the feminine counterpart to solar deities like Horus and Ra; in some traditions, she is described as the consort of Ra and mother of Horus the Elder, while in others, she is Ra’s daughter and Horus’ wife. Hathor also embodied the role of the Eye of Ra, linked to her motherhood symbolism, where Ra was believed to impregnate her daily, resulting in the birth of the sun at dawn, which had a feminine aspect as the eye goddess. This eye goddess then continued the cycle by birthing Ra as her son, symbolizing the Egyptian belief in the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. As the Eye of Ra, Hathor also punished humans on Ra’s behalf, earning her the title of the ‘Distant Goddess’ for her journeys away from Ra’s side; from when she lost control and became violent, Ra would call her back to a gentler, benevolent form, reflecting the dual nature of womanhood as both tender and capable of great rage in Egyptian thought.

Goddess of Music and Joy

The ancient Egyptians, like many pagan cultures, deeply valued music and dance, incorporating them into lively festivals filled with drinking, feasting, and revelry considered divine gifts. Hathor, the goddess linked to music, dance, incense, drunken celebrations, and flower garlands, was honored through epithets and worship that reflected these associations. Temple reliefs dedicated to Hathor often show musicians playing lyres, harps, tambourines, and the distinctive sistra. Her connection to drunken revelry stems from the Eye of Ra myths, where she is pacified by beer during her destructive rampage, highlighting the cultural importance of drinking, music, and other human creations. Additionally, the Nile’s red, silt-laden waters were symbolically compared to wine (or beer), further tying natural phenomena to sacred rituals. This has been brought up in other stories, such as in Exodus, with God turning the river to blood.

Goddess of Beauty and Love

Connected to her role as mother and creator, Hathor was also the goddess of love, beauty, and sexuality. Egyptian creation myths describe creation beginning with the god Atum’s act of masturbation, where the hand he used represents the female aspect of creation, personified by Hathor, earning her the epithet ‘Hand of God.’ Demonstrating the Egyptians’ imaginative approach, Hathor was also the consort of various gods such as Ra, Horus, Amun, Montu, and Shu in different forms. In “The Tale of the Herdsmen,” she appears both as a hairy, animal-like goddess and a beautiful naked woman, or a woman wearing red for passion, with her hair symbolizing her sexual allure and beauty.

Goddess of Motherhood and Queenship

Hathor was revered as the divine mother of Horus so was regarded as the divine counterpart to the Egyptian queens. While the Isis and Osiris myth identifies Horus as their son, Hathor's association as Horus’ mother predates this tradition, with many depictions showing her suckling the child Horus even after Isis became established as his mother. This imagery, featuring the goddess’ milk symbolizing royalty, emphasized Horus’ legitimate right to rule. Ancient Egyptians often worshiped divine families consisting of a father, mother, and child; for example, the Dendera Temple honors a trio of a grown Horus of Edfu, Hathor, and their child Ihy, and at Kom Ombo, a local version of Hathor was venerated as the mother of Horus’ son, reflecting the lasting significance of these divine familial bonds.

Figure 3. This painted terracotta Naqada figure of a woman is interpreted as representing Bat, c. 3500–3400 BCE - Brooklyn Museum

Further Importance of the Cow

Images of cattle are commonly found in the artwork of Predynastic Egypt (before c. 3100 BCE), alongside depictions of women with raised, curved arms that resemble the shape of bovine horns (Figure 3). Both motifs are thought to represent goddesses associated with cattle (Hassan 1992: 15). Cows hold a sacred status in many cultures, including ancient Egypt, symbolizing motherhood and nourishment due to their role in nurturing their calves and providing milk to humans. The Gerzeh Palette, a stone artifact from the Naqada II period of prehistory (c. 3500–3200 BCE), features the outline of a cow’s head with inward-curving horns encircled by stars (Figure 4). This palette implies that the cow was connected to the sky, similar to several goddesses from later periods who were depicted in this form: Hathor, Mehet-Weret, and Nut (Lesko 1999: 15–17).

Figure 4. The Gerzeh Palette. Egyptian Museum, Cairo. JE 43103

Figure 5. A detail from the Narmer Palette, Egypt, c. 3100 BCE. The inscribed slab depicts a king identified as Narmer conquering his enemies and subjugating the land. (Egyptian Museum, Cairo).

Although there are earlier indications, Hathor is not clearly mentioned or depicted until the Fourth Dynasty (c. 2613–2494 BC) of the Old Kingdom (Wilkinson 1999: 244–245), even though some artifacts possibly referencing her date back to the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3100–2686 BCE) (Gillam 1995: 214). When Hathor does appear, her horns curve outward, differing from the inward-curving horns seen in Predynastic art (Fischer 1962: 11–13). A bovine deity with inward-curving horns features on the Narmer Palette (Figure 4), an artifact from the dawn of Egyptian history, appearing both atop the palette and on Narmer’s belt or apron. Egyptologist Henry George Fischer proposed this figure might be Bat, a goddess later depicted with a woman’s face and inward-curling horns, resembling the curve of cow’s horns (Fischer 1962: 11–13). However, Egyptologist Lana Troy identifies a passage in the late Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts linking Hathor to the "apron" of the king, akin to the goddess on Narmer's garments, suggesting the goddess on the Narmer Palette may be Hathor rather than Bat (Wilkinson 1999: 244–245, Troy 1986: 54).

But, in the Fourth Dynasty, Hathor quickly gained prominence (Lesko 1999: 81–83). She replaced an earlier crocodile god worshipped at Dendera in Upper Egypt to become its patron deity, and gradually absorbed the cult of Bat from the neighboring region of Hu, leading to a fusion of the two goddesses by the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC) (Fischer 1962: 7, 14–15). The theology surrounding the pharaoh during the Old Kingdom emphasized the sun god Ra as king of the gods and the earthly king’s divine father and patron. Hathor rose alongside Ra, becoming his mythological wife and thus the divine mother of the pharaoh (Lesko 1999: 81–83).

The minor deity Neferhotep of Hu is another child that is said to be connected to Hathor, though that looks more like a holdover from Bat since they were from the 7th Nome of Upper Egypt — the same as Bat — which was referred to as Sesheshet (Sistrum), the instrument of Hathor and where she later became the primary deity (El-Sharkaway 2010). The main city was referred to as Hu(t)-sekhem (Ancient Egyptian: Ḥw.t-Sḫm), which became abbreviated as Hu, and led to the Arabic name Huw.

Death and Afterlife

Hathor transcended the boundary between life and death with ease, moving into Duat—the realm of the dead—as naturally as she traveled to foreign lands. References to her appear in numerous tomb inscriptions dating back to the Old Kingdom, where the Egyptians trusted her to guide souls into Duat and aid their passage into the afterlife. At times, Hathor was linked with Imentet, the goddess representing the west and the embodiment of necropolises. The Theban Necropolis was often illustrated as a mountain from which a cow emerged, symbolizing this connection. In New Kingdom writings, the Egyptian afterlife is depicted as a lush, abundant garden, and Hathor, revered as a goddess of trees (the sycamore), was believed to supply the deceased with fresh air, nourishment, and water. Through this role, she became an emblem of a serene and joyous afterlife (Dhar 2024).

Figure 6.The Pharaoh with Horus and Hathor. From the tomb of Horemheb/Haremhab in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt, in the last part of the 18th dynasty (Dhar 2024).

Major Associations:

In Egyptian mythology, Hathor is one of the main cattle deities as she is the mother of Horus and Ra and closely associated with the role of royalty and kingship (Mark 2009). Hathor is connected to the celestial sky, the sun, and the afterlife, often depicted in the barge of the sun god Ra. She is also associated with the star Sirius, the Nile River, and the concept of rebirth.

Figure 7. Hathor welcoming Seti I into the afterlife, 13th century BCE.

Figure 8. Hesat as a cow lying down (Wiki Commons).

Hesat is one of Hathor's manifestations, and is another ancient Egyptian goddess in the form of a cow (Mark 2009). She is shown as a pure white cow carrying a tray of food or the solar disk between her horns with udders flowing with milk which were said to provide humanity with milk—the word for which is “hesa” (called "the beer of Hesat") (Hill 2010). [The “t” at the end of the word/name makes it feminine.] This is also what the Milky Way was thought to be in Egyptian mythology; it was considered a pool of cow's milk. The Milky Way was deified as a fertility cow-goddess by the name of Bat (another example of “Ba” [part of the soul] + the feminine “t” ), who was also later syncretized with Hathor. The two versions of the goddess (or goddesses) look very similar. Really only having the different headdresses and the scepter she is holding. But the connection may have gone deeper, but I’ll dive more into that later.

Figure 14. Drawing of the Goddess bat, the possible precursor to Hathor (PharaohCrab)

In her form as Hesat, she is also closely associated with the primeval divine cow Mehet-Weret, a sky goddess whose name means "Great Flood", bringing the inundation of the Nile River, fertilizing the land (Mark 2009). In particular, she was said to suckle the pharaoh and several ancient Egyptian bull gods, such as Mnevis, the living bull/mer-bull god and their children, worshipped at Heliopolis. A distinct archaeological connection was show n in that the mothers of Mnevis bulls were buried in a cemetery dedicated to Hesat. Plus, for more cow symbolism, other feminine bovine deities not already mentioned include Sekhat-Hor and Shedyt, with their masculine counterparts including Apis, Mnevis, Sema-wer, and Ageb-wer (Von Lieven 2012).

In addition, in the Pyramid Texts, Hesat is said to be the mother of Anubis and the deceased king, but not Hathor, showing that in certain periods or areas, they weren’t the same goddess, but the cults were combined somewhere down the timeline.

Ptolemaic times (304–30 BCE), she was closely linked with the goddess Isis (Wilkinson 2003). Earlier, however, Hathor was connected with the goddess Sekhmet, as a transformation act which I’ll go over in her origins (Mark 2009).

Symbols:

As should be obvious by now, Hathor’s sacred animal is the cow, and she is often depicted with cow's ears or horns. In her role as goddess of beauty, she was the patron of cosmetics, so wearing cosmetics was seen as a form of worship to Hathor, and offerings to her of mirrors or cosmetic palettes were common. Mirrors, make-up, and jewellery will, therefore, often have her face featured on them. She is also associated with the sistrum (a rattle-like percussion musical instrument) that she played to drive evil away from the land (Bhot 2022). Because of her ties to dance, music, and parties, the instrument also exhibits her face. Connected to other aspects of her mythology Hathor can also be symbolized by a lioness or a falcon. And finally, the solar disk (showing her sky goddess influence).

Places of Worship:

Hathor’s main temple was in Dendera, Upper Egypt, but her cult spread throughout. As a goddess of love she was worshipped by both men and women, and both male and female priests served in her temples. There were many shrines dedicated to Hathor throughout Egypt and beyond—in Nubia, Sinai, Byblos, and other places where Egypt had influence and control. More temples were dedicated to Hathor than to any other Egyptian goddess (Graves-Brown 2010: 166). During the Old Kingdom her most important center of worship was in the region of Memphis, where "Hathor of the Sycamore" was worshipped at the Memphite Necropolis. In the Old Kingdom, most Hathor priests, including top ones, were women, many from the royal family.

During the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE), her statue at Dendera was taken for festivals to the Theban necropolis. At the start of the Middle Kingdom, Mentuhotep II set up a permanent temple for her at Dayr al-Baḥrī (Deir el-Bahari) (Goedicke 1991: 245, 252). At Dayr al-Baḥrī, in the necropolis of Thebes, she became “Lady of the West” and patroness of the region of the dead. In the Late Period (1st millennium BCE), women aspired to be assimilated with Hathor in the next world, as men aspired to become Osiris (Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2025). The nearby village of Deir el-Medina, where tomb workers lived during the New Kingdom, also had temples for Hathor. One temple remained in use and was rebuilt several times, even up to the Ptolemaic Period, long after the village had been abandoned (Wilkinson 2000: 189–190).

During the Middle Kingdom, women were mostly kept out of top priest roles, while queens became more linked to Hathor's worship. Non-royal women stopped holding high priest positions, but women still worked as musicians and singers in temples across Egypt (Gillam 1995: 233–234, Lesko 1999: 243–244). The cult of Ra and Atum at Heliopolis, northeast of Memphis, included a temple to Hathor-Nebethetepet that was probably built in the Middle Kingdom. A willow and a sycamore tree stood near the sanctuary and may have been worshipped as manifestations of the goddess (Quirke 2001: 102–105). During the New Kingdom, the temple of Hathor of the Southern Sycamore was her main temple in Memphis (Gillam 1995: 219–221). At that site, she was described as the daughter of the city's main deity, Ptah (Vischak 2001: 82). A few cities farther north in the Nile Delta, such as Yamu and Terenuthis, also had temples to her (Wilkinson 2000: 108, 111).

Cusae, the city known to the ancient Egyptians as Qis or Kis, was the capital of the 14th Nome of Upper Egypt and during the Middle Kingdom it was another cult center for Hathor (Samakie n.d.). Located on the west bank of the Nile, it also had the Meir necropolis, a cemetery used during the Middle Kingdom for the tombs of local aristocrats. While the city itself continued through the New Kingdom and the Roman Period, it doesn’t appear that the Hathor cult continued as strongly.

Figure 23. Cusae by Roland Unger, GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0, via Wikimedia Commons

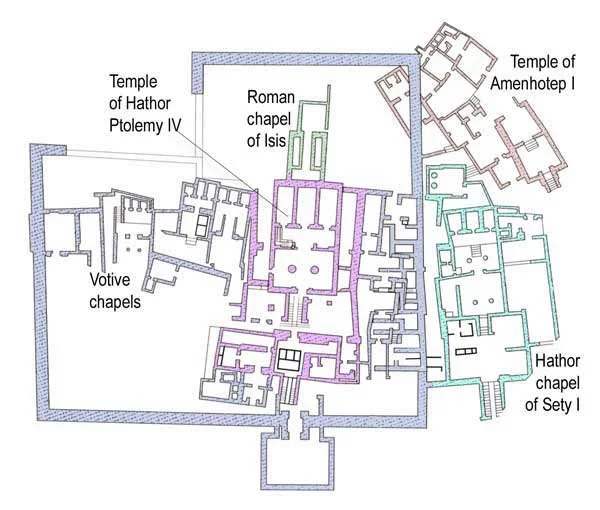

The Hathor Temple is in the "workers' village-settlement" of Deir el-Medina. It started being built by Ptolemy IV Philopator (221–205 BCE) and continued during the reigns of Ptolemy VI Philometor (180–164; 163–145 BCE), Ptolemy VIII and Euregetes II (170–163; 145–116 BCE). The Ptolemaic era temple is one of the largest structures in the workers' village of Deir el-Medina. It was dedicated to goddesses Hathor and Ma’at. Archaeologists working on the site for the Madain Project found that the vestibule (small entrance hall) contains two papyrus columns, which are done in the late period style, and the walls are decorated with scenes of Ptolemy VI worshipping various gods. The main hall leads to three chapels; the door of the Central Chapel, which was completed in circa 220 BCE, was dedicated to Hathor and its entrance was accordingly decorated with a frieze of seven Hathor heads. (Deir el-Medina ("Ptolemaic Temple of Hathor (Deir el-Medina) - Madain Project (en)", 2022). Luckily, it wasn’t torn down during the Christian era, and instead, the temple of Hathor was converted into a church, where the Egyptian Arabic name of Deir el-Medina ("the monastery of the town") is from.

On the right side and to the north of the Deir el-Medina Temple, on a slope in front of Amenhotep I Temple ruin, there are the remains of the Hathor Chapel with some carved relief stone blocks depicting Hathor. Seti I (1294-1279 BCE) built the chapel for the workers of the village that millenia later would become Deir el-Medina which was originally built by people serving Amenhotep I (who ruled from 1526 to 1506 BCE). Since he built the village for the workers, the villagers built the Amenhotep I Temple, just above where the Hathor chapel would be built later and dedicated it to him. Amenhotep was deified upon his death and made the patron deity of the village. (Adams 2015).

Other than her important temples, she also had a shrine at Edfu inside the Temple of Horus. This temple and shrine, which were built in the Ptolemaic Kingdom between 237 and 57 BCE, was the site of the “Festival of the Beautiful Meeting,” celebrating the sacred marriage of Horus and Hathor after Hathor traveled south from Dendera (approximately 168 km away, about a 2 day walk) (David 1993: 99). Hathor’s biggest festival was her annual reunion with Horus, which was celebrated in the third month of the Egyptian summer. At the conclusion of a grand procession, her statue, which was housed in Dendera, would be reunited with the Horus statue in the temple at Edfu. The two statues then participated in various rituals and were placed together in a chamber for the night to get reacquainted. Thousands of pilgrims came to see the sight and stayed on to participate in celebrations that followed over the next fourteen days.

Another popular Hathor festival was held on New Year’s Day, which was considered the anniversary of her birth. Before the sun rose, Hathor’s priestesses brought her statue out of the temple and presented it to the rising sun. Afterwards, there was much rejoicing, and the day ended in music, drinking, and dance.

Dendera was Hathor's oldest temple in Upper Egypt and dates to at least the Fourth Dynasty (Gillam 1995: 227). After the end of the Old Kingdom it surpassed her Memphite temples in importance (Vischak 2001: 83). Dendera became the site of her greatest cult center. The temple complex is one of the best preserved in Egypt and covers 40,000 square meters, which is surrounded by a mud-brick wall for the sacred space. The complex also includes, a series of chapels dedicated to other gods and goddesses, one to Osiris, a sacred pool, a birth house in the temple, and a necropolis containing burials dating from the Early Dynastic Period to the First Intermediate Period with some foundations date to the reign of King Khufu, the builder of the Great Pyramid (Hathor | The Cow Goddess of Love, Joy and Motherhood n.d.).

The Egyptians referred to Hathor as the “Mistress of Dendera” because it was the center of her worship. Dendera was the capital of the 6th Nome of Upper Egypt (next to the 7th Nome where Haset was worshipped). After egyptologists cleaned the years of soot off of the ceiling in one of the main halls some of the best preserved ancient paintings were revealed. (Hathor | The Cow Goddess of Love, Joy and Motherhood n.d.). Many kings made additions to the temple complex through Egyptian history. The last version of the temple was built in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods and is today one of the best-preserved Egyptian temples from that time (Wilkinson 2000: 149–151).

—And—

Hathor Outside the Nile River in Egypt

As mentioned earlier Hathor was commonly worshipped outside of the Egyptian empire. Another to add to the list was Canaan in the 11th century BCE, which was ruled by Egypt at that time, at her holy city of Hazor. The Old Testament claims that it was destroyed by Joshua (Book of Joshua 11:13, 21), but we still had the Sinai Tablets, which show that the Hebrew workers in the turquoise mines of Sinai about 1500 BCE worshipped Hathor who was called “Lady of Turquoise”. She was the same goddess they identified with the goddess Astarte from Phoenicia, who is also Ishtar from Mesopotamia. Plus, some theories state that the golden calf mentioned in the Bible was meant to be a statue of the goddess Hathor (Exodus 32:4-32:6.). Although it is more likely to be a representation of the 2 golden calves set up by Rehoboam, an enemy of the Levite priesthood, which marked the borders of his kingdom.

The Greeks also loved Hathor and equated her with their own goddess of love and beauty, Aphrodite.

Several ancient myths refer to a serpent of light residing in the heavens. While this is believed to have been inspired by the Milky Way (a similar allusion to the ouroboros), I couldn’t find any that connect to Hathor or a cow. She wouldn’t be connected to snakes, that’s the Uraeus’ position.

Art and Architecture:

Hathor is frequently depicted in art, sometimes as a cow, a woman with cow's horns, or a woman with a cow's head. She was also incorporated into temple architecture, appearing as columns or pillars in some buildings.

— The final image shows that Hathor and Bat were separate enough deities to be distinguished people and that this was carved while the king was still alive (his legs are separated).

Festivals

Many of Hathor's annual festivals involved drinking and dancing with a ritual purpose, aiming to induce religious ecstasy, which was rare in ancient Egyptian religion. Graves-Brown suggests that revelers sought an altered state of consciousness to interact with the divine. One example is the Festival of Drunkenness, commemorating the return of the Eye of Ra, celebrated on the twentieth day of the month of Thout at Hathor's temples and those of other Eye goddesses. Originating as early as the Middle Kingdom, it is best known from Ptolemaic and Roman times. The festival's dancing, eating, and drinking symbolized life, abundance, and joy, contrasting the sorrow, hunger, and thirst linked to death.

Another festival, the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, began in the Middle Kingdom in Thebes. During this, Amun's cult image from Karnak toured temples in the Theban Necropolis while the community visited ancestors' tombs to celebrate. Hathor joined this festival only in the early New Kingdom, after which Amun’s overnight stay at temples in Deir el-Bahari came to be interpreted as his sexual union with her.

Several temples during Ptolemaic times, including Dendera, celebrated the Egyptian new year with ceremonies aimed at revitalizing the temple deity’s image through contact with the sun god. In the days before the new year, Dendera's statue of Hathor was taken to the wabet, a special room decorated with sky and sun imagery. On the first day of the new year, the first day of Thoth, the Hathor statue was carried to the roof to be bathed in actual sunlight (Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996: 193–198).

The best-documented festival focused on Hathor is the Ptolemaic Festival of the Beautiful Reunion, lasting fourteen days in the month of Epiphi (Bleeker 1973: 93, Richter 2016: 4). During this festival, Hathor's cult image from Dendera was carried by boat to various temple sites, ending at the Temple of Horus at Edfu, where Hathor’s statue met Horus of Edfu’s statue and were placed together (Bleeker 1973: 94). On one day, the images were taken to a shrine said to hold primordial deities such as the sun god and the Ennead, where the divine couple performed offering rites (Verner 2013: 437–439).

Many Egyptologists interpret this festival as a ritual marriage between Horus and Hathor, but Martin Stadler argues it signifies the rejuvenation of the buried creator gods instead (Stadler 2008: 4–6). C. J. Bleeker viewed the Beautiful Reunion as a celebration of the return of the Distant Goddess, referencing temple texts related to the solar eye myth (1973: 98–101). Barbara Richter suggests the festival represented all these aspects simultaneously, noting that the birth of Horus and Hathor’s son Ihy was celebrated nine months later at Dendera, implying that Hathor’s visit to Horus symbolized Ihy’s conception (2016: 4, 202–205).

The third month of the Egyptian calendar, Hathor or Athyr, was named after the goddess. Celebrations for her happened all month, but they are not mentioned in the Dendera texts (Verner 2013: 43).

Mythological Origins:

There aren’t many myths about where Hathor came from… While we can see that her importance waned in later years, it is still so important that she was the goddess of so many things and lasted for so long. But with her commercialization (in a way) had her other origin myths been subsumed or overtaken? Mostly, we have myths where she’s just there, the wife or mother of some other god, as if her presence is just a given. Hathor and the roles she fulfilled did not disappear after the Ptolemaic dynasty anyway. They were just given to another goddess, Isis, and the mythology around them changed very little in the Ptolemaic years.

The mythical origins of Hathor are disputed because, depending on the message, the tellers had to relay that she had to symbolized different things. As previously mentioned, Hathor was a goddess of such ancient origin that she encompassed a vast range of mythological and religious functions. This complexity makes it challenging to encapsulate her classical attributes succinctly, particularly since she frequently absorbed local goddess cults and they integrated their roles into her own.

Some sources claim that she was the primordial personification of the Milky Way. Hathor was the cosmos, and in her cow avatar, she produced the milk that became the sky and the stars that flowed from her udders. For 3,000 years, Mehturt (also spelt Mehurt, Mehet-Weret, and Mehet-uret), meaning great flood, a direct reference to her being the Milky Way, was another name for Hathor. (Pinch 2002: 163).

Another possibility is that Hathor’s worship originated in early dynastic times (3rd millennium BCE) (Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2025). Possibly her oldest version (at least in Egypt) was her connection to Bat, the cow goddess worshipped in the adjacent 7th Nome (was all discussed earlier), who was associated with fertility and success. She is one of the oldest Egyptian goddesses dating from the early Predynastic Period (c. 6000-3150 BCE). Bat is depicted as a cow or a woman with cow ears and horns, and is most probably the image at the top of the Narmer Palette (c. 3150 BCE), as she was associated with the king's success (Figure 5). She blessed people with success owing to her ability to see both the past and the future. Eventually, she was absorbed by Hathor who took on her characteristics.

Sekhmet or Hathor

But other stories about the beginnings of Hathor are less benevolent. She was the hungry, violent deity that Ra unleashed upon humans to punish humankind for their wrongs. Hathor was closely connected with the sun god Re of Heliopolis, whose “eye” or daughter she was said to be. (Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2025). When Ra unleashed Hathor upon the world, she tore up homes and destroyed crops, and wreaked destruction. She either was already, or at this point transformed into the goddess Sekhmet in her destructive form. She ventured far into Egypt, away from Ra’s side, and did a ton of killing. When the other gods pointed out to Ra that there would be no humans left at this rate, Ra had to think of a plan to call Sekhmet out of her bloodthirst. He asked Tenenet, the goddess of beer, to brew a red beer, or red wine (so the god would probably be Shesmu). In some versions, the gods poured gallons into the Nile and Sekhmet drank this, thinking it was blood, and fell asleep. When she woke up, she had become the benevolent mother goddess again. The alternative is that Sekhmet is a completely separate goddess who just chills out, presumably with the headache.

Alternatively, some stories say that Hathor became enraged because of Ra’s mistreatment by the Egyptians. She chose to transform into Sekhmet and began destroying the people of Egypt. The other gods tricked her into drinking milk and she changed back into Hathor.

The Hathor and Osiris Myth

Isis is the main female deity involved in the Osiris myth, as his wife who tried to resurrect him. However, Hathor appeared in the story in a minor way. When Horus the Younger, the son of Isis and Osiris, challenged Set, they had to take part in a trial before nine important gods. The most important of these is Ra, who is referred to as Hathor’s father in this myth, which makes the next part extremely bizarre/creepy.

When Ra begins to grow tired and bored of the trial, Hathor appears before him and reveals to him her naked body. Osiris is immediately restored and goes back to passing judgment for the trial. The symbolic meaning of this story may be the balance of masculinity and femininity and how the latter can exercise control if the former is slipping.

Wife of Thoth (or Toth)

When Horus was merged with Ra under the name Ra-Herakhty, Hathor’s role became ambiguous, as she was traditionally both Ra’s consort and Horus’s mother. To address this, Ra-Herakhty was given a new wife, Ausaas, to clarify his marital relationship. Yet, this solution raised the question of Hathor’s position as his mother—implying Ra-Herakhty was Hathor’s offspring rather than a creator deity.

In regions where Thoth’s cult was greater than Ra’s, Thoth was seen as the creator. Consequently, Thoth was considered the father of Ra-Herakhty, making Hathor, as his mother, the spouse of Thoth in this narrative. Within this version of the Ogdoad cosmogeny, Ra-Herakhty appeared as a young child, often named Neferhor. Accordingly, Hathor was frequently portrayed as a nurturing female figure, depicted nursing the divine child.

Generally in mythology, Thoth's wife was identified as Seshat (the goddess of poetry), many of Seshat's attributes were later assigned to Hathor. Because Seshat was also linked to record-keeping and serving as a witness during the judgment of souls, these roles were also credited to Hathor. Combined with her status as the goddess of all that is good, this led to Hathor being described as Nechmetawaj (also spelled Nehmet-awai or Nehmetawy), which means "the one who expels evil." Additionally, Nechmetawaj can be interpreted as "the one who recovers stolen goods," and in this aspect, Hathor assumed the role of goddess of stolen goods.

Outside the Thoth cult, it was essential to uphold Ra-Herakhty’s (i.e., Ra’s) status as self-created, emerging solely from the primal forces of the Ogdoad. Therefore, Hathor could not be regarded as Ra-Herakhty’s mother. In her role associated with death—welcoming the newly departed with food and drink—Hathor came to be seen as the cheerful consort of Nehebkau, the guardian of the underworld’s entrance and binder of the Ka. Despite this, she maintained the name Nechmetawaj, reflecting her vital role as the restorer of stolen goods, a function deeply valued and recognized by society.

Myths As Written…

Hathor is one of the most prominent deities in ancient Egyptian mythology, embodying multifaceted aspects such as love, beauty, fertility, music, and motherhood. As a goddess whose attributes span various domains, she played a pivotal role in Egyptian religious and cultural life. Her image is frequently represented with the horns of a cow, often cradling a sun disk between them, symbolizing her connection to both the nurturing aspects of agriculture and the divine realm. These iconic depictions emphasize her strengths as a motherly figure and a protector, especially in matters related to childbirth and fertility (Chapón et al. 2024; Mahmoud, 2012). Hathor’s dual nature as both nurturing and potent is integral to understanding her overall significance within the pantheon of ancient Egyptian deities (Tassie, 2003).

While she was known as the goddess of love and beauty, Hathor was also frequently associated with music and dance, as well as fun and kindness, forming a crucial part of ancient Egyptian festivities and ritual practices. Worshipers believed that through music, they could connect with the divine, and Hathor’s priestesses often led celebrations that included singing and dancing (Moussa et al., 2009). The Sistrum, a musical instrument associated with her worship, became a symbol of her divine presence in ritual settings. This relationship between music and worship reflects the broader cultural importance of artistic expression in Egyptian society (Karam, 2024). Thus, Hathor's associations with joyous celebration highlight the integral role of women in religious practices, as her temples often housed female priests who served as intermediaries between the goddess and the worshippers (القاضى et al., 2019).

Hathor’s significance extended into the realms of health and healing. Temples dedicated to her, particularly the temple at Dendera, were seen as places of medical care where individuals sought divine assistance for ailments. Evidence indicates that these temples served as sanctuaries for physical healing and spiritual renewal, wherein patients believed they could interact with the goddess’s divine essence (Abouelata, 2018). The goddess not only represented health in a physical sense but also symbolized psychological well-being, further reinforcing the notion of a holistic approach to health in ancient Egyptian society.

The association of Hathor with childbirth is prominent in ancient Egyptian culture; she served as a protector of women during labor and was often invoked in maternal and fertility rituals. Tattoos linked to Hathor have been discovered on various female mummies, suggesting a ritualistic marking honoring her, believed to bring protection and fertility (Tassie, 2003)Karev, 2022). This aspect of her worship aligns with broader themes of femininity, fertility, and motherhood that permeate ancient Egyptian beliefs. The frequent imagery of Hathor as a nurturing figure reflects the societal values surrounding maternal roles and femininity, a critical aspect of the ancient Egyptians’ worldview (Tassie, 2003).

In addition to these nurturing attributes, Hathor was also venerated as a goddess of the afterlife, associated with the mystical journey that souls undertook after death. This dimension added depth to her mythology, signifying that she not only cared for the living but also offered guidance to the deceased. This multifaceted portrayal is crucial to understanding her complexity as a deity who enveloped life, love, joy, and mortality within her narrative. Such attributes empowered her followers to regard her as an eternal guardian, capable of influencing both temporal and spiritual aspects of existence.

The cultural practice of representation in art also highlights Hathor’s pervasive influence. Her depictions are found in tombs, temples, and on everyday items, emphasizing her legitimacy as both a protective force and an object of veneration. The artistic renditions of Hathor demonstrate how the ancients articulated their beliefs and connected their everyday lives to the divine. Statues and reliefs often portrayed her in conjunction with her son Horus and her counterpart Isis, reinforcing familial themes central to her worship (Mahmoud, 2012; Kozma, 2005). The artistic representations served not only religious purposes but also celebrated the interconnectedness of human experiences with divine attributes.

Moreover, her role as a celestial goddess illustrates the synthesis of earthly and divine realms in ancient Egyptian thought. As the sky goddess, Hathor’s identity bridges daily life with the cosmos, representing the cyclic nature of existence, which was fundamental in Egyptian religious philosophy. This celestial connection resonates with the Egyptians’ agricultural calendar, aligning their rituals and festivals with the cycles of nature, further intertwining Hathor with themes of fertility and regeneration. These elements manifest a comprehensive framework through which the ancient Egyptians interpreted their environment, allowing them to navigate life’s challenges and uncertainties with the goddess’s guidance and support.

Hathor’s worship was not confined to the urban centers in Egypt; it extended into foreign territories, revealing her influence beyond the Nile Valley. Archaeological traces indicate that her cult reached as far as the Levant and was syncretized with indigenous practices, suggesting an adaptive quality that allowed her iconography and attributes to be reinterpreted in various cultural contexts. This adaptability underscores the universal themes of love, beauty, and protection that resonated with diverse populations, allowing them to connect with her in a manner that suited their own beliefs and practices.

In archaeological studies, the extensive findings in temples dedicated to Hathor, such as those in Dendera, continue to offer insights into the rituals and daily lives of ancient Egyptians. Here, the remnants of inscriptions, and artifacts reflect a society deeply interwoven with the physical manifestation of divine presence through sacred sites and objects. These served to reinforce the social structure, aligning community identity with reverence for the goddess in the everyday practices were within ancient Egyptian life.

Part 2 — Stargate Version

Figure 46. Episode 14 of season 1, “Hathor” from Stargate SG-1 (1997). From IMBD.

Hathor is portrayed as a significant and complex character in both ancient Egyptian mythology and the science fiction series Stargate SG-1, although her presentation differs markedly between the two contexts. In ancient Egyptian mythology, Hathor is revered, she embodies nurturing qualities, symbolized by her association with motherhood and fertility, and is often depicted in art as a woman with cow horns cradling the sun (Bondarenko, 2022). On the other hand, in Stargate SG-1, Hathor is depicted as a formidable antagonist, characterized by a menacing presence that invokes fear among characters and symbolizes the darker aspects of power and manipulation (Gil, 2015; Malley, 2018).

In ancient mythology, Hathor represents joy and abundance, celebrated for facilitating positive aspects of life, such as love and fertility. The temples dedicated to her were places of worship administered predominantly by female priests who performed rituals to honor her (Bondarenko, 2022). The essence of Hathor in Egyptian culture reflects the societal reverence for feminine power and the nurturing roles women played. In contrast, the Stargate SG-1 adaptation downplays her nurturing qualities and emphasizes her portrayal as a manipulative goddess who uses her powers to control and dominate others, presenting a narrative focused on conquest rather than compassion (Gil, 2015; Malley, 2018). This shift underscores the show's thematic focus on conflict and the moral challenges faced by its protagonists.

Hathor’s evolution into a villainous character in Stargate SG-1 also contrasts with her mythological attributes of protection and healing. In Egyptian mythology, she was associated with well-being and healing, often invoked for protection during childbirth (Bondarenko, 2022). In the series, her attributes are inverted, portraying her as a threat through which characters must navigate danger. This transformation serves the narrative of conflict that underpins much of science fiction, employing ancient mythological constructs to explore themes of power, fear, and survival in a high-stakes storyline (Gil, 2015; .

Furthermore, within the context of Stargate SG-1, Hathor's character is imbued with aspects of seduction and sexual manipulation. This reflects the ancient perception of her as a goddess of love and beauty, but the portrayal shifts to a more predatory interpretation focused on the use of sexual allure as a tool for achieving her ends (Gil, 2015; . This aspect diverges from the more wholesome understanding of love and intimacy associated with the goddess in Egyptian mythology. While her essence as a figure of beauty remains, the moral landscape around her character in the series signifies a broader commentary on the potentially destructive aspects of beauty and power.

The portrayal of Hathor as a goddess who commands a group of loyal followers, manipulating their will through supernatural means, contrasts significantly with her mythological roots as a nurturing force for family and community. The ancient Egyptians viewed her as a figure of solace and communal harmony. In Stargate SG-1, however, Hathor’s followers are depicted almost as extensions of her will, indicating a loss of individuality and autonomy, sacrificed in the service of her overarching ambitions (Gil, 2015; . This dichotomy emphasizes how contemporary storytelling can reinterpret ancient myths to serve modern narratives, often prioritizing conflict resolution over themes of healing and mutual support.

The thematic focus on military and space adventures in Stargate SG-1 also diverges from the ancient cultural interpretations of Hathor, which were inseparably linked to the rhythms of agriculture, the cycles of nature, and the emotional life of the community (Bondarenko, 2022). In the series, Hathor does not serve as a reminder of harmony but rather instills a sense of impending doom, marking her as an enemy the protagonists contend with. This alteration reflects the broader paradigms of science fiction, where characters often represent either the ideal or the antithesis of human experience, encapsulating moral dilemmas faced by individuals when confronting power and authority.

Moreover, the representation of Hathor in Stargate SG-1 highlights the broader cultural and narrative explorations in science fiction, where ancient mythologies are reinterpreted through modern lenses. The series takes creative liberties, using her figure to explore contemporary issues of gender, agency, and power dynamics in a universe filled with conflict and technological advancements. This contrasts profoundly with her original role in ancient myths, which emphasized connection, community, and family bonds. Instead of being an ally in trials, in Stargate SG-1, she embodies competition and manipulation, challenging the heroes at every turn (Gil, 2015; Malley, 2018).

Conclusion

While both the ancient Egyptian goddess Hathor and her depiction in Stargate SG-1 represent themes of love, beauty, and influence, the contexts in which these themes manifest differ significantly. The balance shifts from nurturing warmth and community support in traditional mythology to a more adversarial and predatory interpretation in the science fiction narrative, showcasing the complexities of adapting ancient lore to contemporary storytelling frameworks. This transformation brings forth a critical analysis of how historical figures can evolve across cultures and genres, illuminating the ever-changing nature of mythology in the fabric of human experience.

But if you look at what the Egyptians, and really so many other cultures, did with her in combining her with other goddesses and taking over all of their domains… Seems exactly what the Stargate Villain Hathor would have done, with perfect makeup and a crooked smile on her face.

During the episode of her first appearance (S1E4), Daniel Jackson compares her to other deities of love such as Aphrodite and others. Aphrodite is the Greek goddess of love and sexuality, which is a bit more than half the story because, while Aphrodite was a mother, she was not really a goddess of motherhood until she became combined with other goddesses in Roman mythology.

Aphrodite was a flighty vixen, much more attuned to the character in Stargate. She was portrayed as a manipulative figure who punished people for being pretty, hated some individuals, and made others fall in love unwillingly. In fact, she is the reason the events of The Iliad occurred and the Trojan War began. She coveted the golden Apple of Discord, which led to a famous contest between her, Hera, and Athena.

Zeus did not want to choose who deserved the Apple, so he appointed Paris to make the decision. Paris awarded the Apple to Aphrodite because she promised him the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen of Troy. At that time, Helen was actually Helen of Sparta and was already married to Menelaus, the King of Sparta. This decision ultimately caused the fallout that led to the Trojan War.

Odysseus had made deals with all the other kings of Grace to fight alongside him if anyone threatened his and his wife's union. This was Odysseus's idea in the area, and subsequently, you hear more about him getting back to his wife Penelope (another daughter of Sparta) in The Odyssey, of course. But my point is that the sexual aspect is much more associated with Aphrodite than with Hera. Hera was a generous goddess who raised Heracles to protect him not only from harm but also from the influence of sex and any other gods that might try to hurt him. She was the goddess of motherhood and a goddess of love, but that doesn't automatically mean that her domain was limited to sex alone. She was a goddess of sex too, but she encompassed many facets of love beyond just the physical. Obviously, there is the element of persuasion that can be wielded through sex, especially related to Aphrodite. I often wonder if Hera was actually like a beautiful woman. I might be criticized for this by Aphrodite's followers, but since love can be so complex and sometimes ugly, I wonder if Hera’s nature was as stern or harsh on the outside as well as in character.

*Myth of Osiris getting put back together by Anubis and Isis

Osiris, once the benevolent king of Egypt, was brutally murdered by his jealous brother Set. At a god party, which I assume is way cooler than mortal parties… but maybe not based on this “game” or “contest” tricked Osiris into lying in a beautifully crafted wooden sarcophagus, by saying it would be given to whoever fit into it. Set had had it made specifically for Osiris, so he obviously fit. Once Osiris was inside, Set sealed and threw it into the Nile.

In some versions, the chest drifted away, eventually becoming lodged in a tree, leaving Osiris’s body trapped and lost to the world. In a different version, Isis, Osiris’s devoted wife and sister, embarked on a tireless search to find her husband’s body. After recovering his corpse, she faced a grisly challenge: Set had dismembered Osiris into 14 pieces, spreading them across Egypt to prevent his resurrection. Each body part was sacred, holding immense symbolic power, and Isis meticulously gathered every fragment despite the danger and disgust, but she loved him so was inspired to press on. As the god of embalming and moving into the afterlife, Anubis assisted Isis in the ritualistic process of reassembling Osiris’s body. Together, Isis and Anubis cleansed and embalmed Osiris’s bones, anointing them with precious oils and wrapping them in linen bandages. This process was both physically and spiritually significant, marking the transition from death back to life but in a divine, otherworldly form. The restoration was not a simple reattachment of limbs; it was a sacred rite imbued with magical power. The act of putting Osiris back together symbolized the Egyptian belief in the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Isis’s magic reanimated Osiris, but he did not return among the living—he became the lord of the underworld, ruling over the dead and offering hope of resurrection for humankind.

It was during this period of searching that Horus was conceived.

In the version I originally learned, Set didn’t leave Osiris’ body in the sarcophagus. Instead, he chopped up the box and the body with it and scattered the pieces across the world (Egypt? Sure). It was after this that Isis enlisted Anubis to help her find the pieces and put them back together. To make searching faster and easier, Isis transformed herself into a falcon. After, presumably, months of searching a finding different pieces, Hathor had one last one to find. The penis. Flying over Egypt (again) she found it in the Nile. She fished it out and, having her husband’s dong, decided to boink herself with it. I guess it was still able to cum god juice because she got pregnant and, however much later, gave birth to Horus, the falcon-headed god (since she was a falcon when she got preggers). With Set still on the loose, Horus was generally left with his, aunt?, so Hathor to raise him in safety.

So, you can imagine how weird it was to read that Hathor and Horus were married… grooming or completely disconnected mythologies? You decide.

~For another version of this myth, see OSPs Underworld Myths — Egyptian section (linked to Osiris and Isis myth). I do recommend watching the entire thing HERE.

References:

Abouelata, M. (2018). Travel to the healing centers in the egyptian temples: the prototype of the modern medical tourism. Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies, 8(2), 121-132. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejars.2018.23508

Adams, M. (2015, September 12). Hathor Chapel of Seti I – Deir El-Medina. My Luxor by Bernard M. Adams. https://egyptmyluxor.weebly.com/hathor-chapel-of-seti-i-ndash-deir-el-medina.html#:~:text=At%20Deir%20el%2DMedina%20on,Seti%20I%20%E2%80%93%20Deir%20el%2DMedina

@Ancientegyptblog7. (2023, September 23). Cow, beautiful woman, or both? – video. Ancient Egypt Blog. The Self-Taught Egyptologist. https://www.ancientegyptblog.com/?p=2852#:~:text=By%20ancientegyptblog7,I%20was%20a%20little%20girl! Instagram and TikTok

Bandy, K. (2020). Hathor., 1-1. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah15185.pub2

Bhot, K. (2022). Hathor (deity). EBSCO Information Services, Inc. | www.ebsco.com. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/religion-and-philosophy/hathor-deity#:~:text=Hathor%20is%20one%20of%20the,experiences%20of%20dance%20and%20music.

Bleeker, C. J. (1973). Hathor and Thoth: Two Key Figures of the Ancient Egyptian Religion. With 4 Plates (Vol. 26). Brill.

Bondarenko, N. (2022). The Religious Role of the Egyptian Queen as High Priestess Cult of Hathor. Bulletin of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv History, (154-155), 5-9. https://doi.org/10.17721/1728-2640.2022.154-155.1

Chapón, L., Fernández, J., Alejos, A., & González, A. (2024). Iron Age connectivity revealed by an assemblage of Egyptian faience in central Iberia. European Journal of Archaeology, 27(3), 289-311. https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2024.1

Cooney, K. (2010). Gender transformation in death: a case study of coffins from ramesside period egypt. Near Eastern Archaeology, 73(4), 224-237. https://doi.org/10.1086/nea41103940

David, Rosalie. Discovering Ancient Egypt, Facts on File, 1993. p. 99.

Dhar, R. (2024, March 11). Hathor: ancient Egyptian goddess of many names | History Cooperative. History Cooperative. https://historycooperative.org/hathor/

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (2025, June 27). Hathor. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hathor-Egyptian-goddess.

El-Sharkaway, B. (Ed.). (2010). The Horizon: Studies in Egyptology in Honour of MA Nur El-Din (Vol. 1). Melinda Inn; Morkot, R. (2004). The Egyptians: an introduction. Routledge.

Fischer, Henry George (1962). "The Cult and Nome of the Goddess Bat". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 1: 7–18. doi:10.2307/40000855. JSTOR 40000855.

Gil, S. (2015). Science wars through the stargate.. https://doi.org/10.5771/9781442256200

Gillam, Robyn A. (1995). "Priestesses of Hathor: Their Function, Decline and Disappearance". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 32: 211–237. doi:10.2307/40000840. JSTOR 40000840.

Graves-Brown, Carolyn (2010). Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt. Continuum. ISBN 978-1847250544.

Harrington, Nicola (2016). "The Eighteenth Dynasty Egyptian Banquet: Ideals and Realities". In Draycott, Catherine M.; Stamatopolou, Maria (eds.). Dining and Death: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the 'Funerary Banquet' in Ancient Art, Burial and Belief. Peeters. pp. 129–172. ISBN 978-9042932517.

Hart, George (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, Second Edition. Routledge. pp. 61–65. ISBN 978-0203023624.

Hassan, Fekri A. (1992). "Primeval Goddess to Divine King: The Mythogenesis of Power in the Early Egyptian State". In Friedman, Renee; Adams, Barbara (eds.). The Followers of Horus: Studies Dedicated to Michael Allen Hoffman. Oxbow Books. pp. 307–319. ISBN 978-0946897445.

Hathor | the cow goddess of love, joy and motherhood. (n.d.). https://www.ancient-egypt-online.com/hathor.html

Hill, J. (2010). Hesat. Ancient Egypt Online Ancient Egyptian History and Art. https://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/hesat/#:~:text=Hesat%20(Heset%2C%20Hesahet%2C%20or,Anubis%20were%20worshipped%20in%20Heliopolis.

Hollis, S. (2010). Hathor and isis in byblos in the second and first millennia bce. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.2458/azu_jaei_v01i2_tower_hollis

Huang, H. (2018). Research on the facade image of the goddess hathor in ancient egypt.. https://doi.org/10.2991/ichssr-18.2018.44

Karam, M. (2024). Ancient egyptian dances between past and today. International Journal of Advanced Studies in World Archaeology, 7(1), 24-32. https://doi.org/10.21608/ijaswa.2024.221187.1036

Karev, E. (2022). ‘mark them with my mark’: human branding in egypt. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 108(1-2), 191-203. https://doi.org/10.1177/03075133221130094

Kozma, C. (2005). Dwarfs in ancient egypt. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 140A(4), 303-311. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.31068

Lesko, Barbara S. (1999). The Great Goddesses of Egypt. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806132020.

Mahmoud, H. (2012). Microanalysis of blue pigments from the ptolemaic temple of hathor (thebes), upper egypt: a case study. Surface and Interface Analysis, 44(9), 1271-1278. https://doi.org/10.1002/sia.4999

Malley, S. (2018). Stargate SG-1., 44-58. https://doi.org/10.3828/liverpool/9781786941190.003.0003

Mark, J. J. (2009, September 02). Hathor. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/Hathor/.

Meeks, D., & Favard-Meeks, C. (1996). Daily life of the Egyptian Gods. Cornell University Press.

Moussa, A., Kantiranis, N., Voudouris, K., Stratis, J., Ali, M., & Christaras, V. (2009). The Impact of soluble salts on the deterioration of pharaonic and Coptic wall paintings at Al Qurna, Egypt: Mineralogy and Chemistry*. Archaeometry, 51(2), 292-308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.2008.00422.x

Pinch, G. (2002). Handbook of Egyptian mythology. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Ptolemaic Temple of Hathor (Deir el-Medina). Madainproject.com. (2022). Editors, Retrieved on July 22, 2025, from https://madainproject.com/ptolemaic_temple_of_hathor_(deir_el_medina)

Quirke, Stephen (2001). The Cult of Ra: Sun Worship in Ancient Egypt. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500051078.

Richter, B. A. (2016). The Theology of Hathor of Dendera: Aural and Visual Scribal Techniques in the Per-Wer Sanctuary (Vol. 4). Lockwood Press.

Robins, A. (2019). The Alpha Hypothesis: Did Lateralized Cattle–Human Interactions Change the Script for Western Culture? Animals, 9(9), 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9090638

Samakie, A. (n.d.). CUSAE | Archiqoo. https://archiqoo.com/locations/cusae.php

Tassie, G. (2003). Identifying the practice of tattooing in ancient Egypt and Nubia. Papers From the Institute of Archaeology. 14(0). https://doi.org/10.5334/pia.200

Troy, Lana (1986). Patterns of Queenship in Ancient Egyptian Myth and History. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-9155419196.

Varadharajulu, S. (2020). The burden of a child: examining the effect of pregnancy on women’s power in ancient Egypt and Greece. https://doi.org/10.22541/au.158680351.16512229/v2

Vischak, Deborah (2001). "Hathor". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 82–85. ISBN 978-0195102345.

Verner, M. (2013). Temple of the world: sanctuaries, cults, and mysteries of ancient Egypt. American University in Cairo Press.

Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500051009.

Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 173–174.

Wilkinson, Toby (1999). Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-0203024386.

Xu, B. (2019). The ties between Hathor and the weaver girl (织女). https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/jp9wd

القاضى, م., الحمید, م., & جاد, ن. (2019). Wet nurse in art in Graeco-Roman Egypt. المجلة العلمية لکلية السياحة و الفنادق جامعة الأسکندرية, 16(16 - B), 23-44. https://doi.org/10.21608/thalexu.2019.66645

شلبي, د. (2022). المعبودة حتحور والمعبودة نينخورسنج- دراسة مقارنة. المجلة العلمیة لکلیة الآداب-جامعة أسیوط, 25(82), 1131-1170. https://doi.org/10.21608/aakj.2022.239813